There are an estimated 10 million Americans who are living with lymphedema. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) reports that the incidence of primary lymphedema is from 1 out of 300 to 1 out of 6000 live births. Add to that those with secondary lymphedema brought on by cancer treatments, surgery, or trauma such as that incurred by our military veterans wounded in combat. Clearly the problem is significant. But why is lymphedema practically an unknown disease for so many in the U.S.?

There are an estimated 10 million Americans who are living with lymphedema. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) reports that the incidence of primary lymphedema is from 1 out of 300 to 1 out of 6000 live births. Add to that those with secondary lymphedema brought on by cancer treatments, surgery, or trauma such as that incurred by our military veterans wounded in combat. Clearly the problem is significant. But why is lymphedema practically an unknown disease for so many in the U.S.?

“Part of the problem is the name ‘lymphedema’,” says William Repicci, Executive Director of the Lymphatic Education & Research Network, known as LE&RN.

“Name almost any disease and you will most likely say it by its acronym—MS, AIDS, TB, ALS, etc. Sporadically, you will see people use the acronym ‘LE’ for lymphedema, but generally that’s not the case. In fact, if you look at the CDC website, they not only don’t mention an acronym for lymphedema, the only reference on their ‘Diseases & Conditions A to Z index’ webpage states the following: ‘Lymphedema—see Lymphatic Filariasis.’ Where is the recognition of the 100 million worldwide estimated by the World Health Organization (WHO) to have non-filarial related lymphedema? Where is the recognition of the 10 million Americans who have primary or secondary LE?

“One easily understands why the disease lymphedema was given its name. It is a chronic swelling (edema) caused by the accumulation of fl uid (lymph) when the lymphatic system is damaged. However, this does leave us with a disease name made up of two words that 99% of the world’s population would otherwise never use in their lifetimes. Th is is hardly a winning formula if we want to bring attention to a disease that already faces so many obstacles to being recognized. Embracing the acronym ‘LE’ helps bring the disease into common discourse.”

The Vascular Connection

Repicci’s background is in the development of programs for disabilities and infectious diseases. Over the last fi ve years, in addition to promoting research, his responsibilities at LE&RN have been to broaden awareness and to help educate patients and providers within the lymphatic disease community.

“One thing that really had never come up at LE&RN until about a year ago was the lymphatic/ vascular connection,” says Repicci. “Suddenly, there were inroads being made by Drs. Stan Rockson and Dave Zawieja who serve on our Scientific/Medical Advisory Council. The American College of Phlebology (ACP) featured a lymphatics panel at their conference, and I was most gratified that Stephen Moss then offered LE&RN the symposium video for our website.

Our members and patients began to see the connections and little by little, this has been reinforced by others. For instance, a company that creates pneumatic pumps recently said to me, ‘Bill, you would be a lot more valuable to us if you were more involved in the venous side of things in addition to the lymphatic side. Because the fact is, a high percentage of our patients with venous disease also have lymphedema.’ Little by little the dots have been connected.”

Spreading the Word with Physicians

Repicci estimates that a sizeable number of those with LE in the U.S., and quite possibly the majority, fall into these categories:

- People who are suffering from LE, but have no idea they have a disease and are not seeking treatment.

- Patients who know they have some ailment, but are clueless as to its name and are receiving treatment based on a misdiagnosis.

- Patients who know they have LE but are unable to find knowledgeable medical care as they watch their condition deteriorate. Th is situation leads to a daily fl ow of e-mails to LE&RN from desperate patients looking for help or someone who understands and is willing to listen.

One thing that is clear is that even within the field of lymphatics and LE, physician education in those areas needs improvement. “We also realize that part of the reason that physician’s tend to get frustrated is that LE is not being taught in medical schools and up until now, we have offered very few treatments that doctors generally would dispense for these diseases,” adds Repicci.

Interestingly enough, the medical community is beginning to realize how severe the problem really is. “One promising development is the current discussion between the American Board of Venous and Lymphatic Medicine (ABVLM) and LE&RN focused on working together to create a physician certification program in lymphedema and lymphatic diseases.” Repicci notes,“Interestingly, the first question that came up was ‘Is the reason we haven’t done this so far because the incidence of lymphedema isn’t as great in this country?’”

“When I mentioned the estimated 10 million Americans with lymphedema, the opportunity for our mutual engagement in this challenge became clear. Physician education is key, and a current lack of it is thwarting our progress in meeting the needs of patients who are suffering.

”So how do you interest physicians in taking a new certification course? Recently, a conference call was held with ABVLM and LE&RN representatives to discuss next steps in creating that certification program. “On one hand, you have ABVLM with a membership made up of physicians. To a large degree, these physicians are encouraged to pursue further education because it leads to new treatments they can offer patients,” Repicci says.

He also adds, “LE&RN, on the other hand, has a large patient and therapist base along with our research/medical members. And the dilemma in connecting the needs of these patients to physicians is that there are few treatments for lymphedema at the doctor’s disposal. However, we need doctors to be able to diagnose lymphedema. We need them to educate their patients about the implications of the disease. And we need them to readily disperse the treatments that are available. Patients are already aware of this need, but cannot create this shift in the medical community on their own.”

“However, by combining the efforts of both ABVLM and LE&RN we create a synergy to fuel change. Here we encourage doctors to become certified and at the same time empower patients to make informed choices. Listing certified doctors on the LE&RN website gives patients opportunities to not only find good care, but allows them to become good advocates also.

By this I mean, it empowers them to approach their current doctor and ask if he or she is certified in lymphatics—and if not, why not. Expectation is a powerful motivator. If patients tell physicians that their needs are not being met, I believe their physicians will listen. This could change the current paradigm dramatically.”

The Man Behind the Research

None of this would be happening if it weren’t for the tireless work of Dr. Stanley G. Rockson of the Center for Lymphatic and Venous Disorders at Stanford University. “I see all lymphatic diseases, so I am one of the only people in Stanford’s Department of Medicine that also sees children,” says Rockson. “I see infants and children with congenital and primary forms of LE. While our practice is predominated by cancer-associated problems, we also evaluate people with lymphatic vascular malformations, lymphangiectasia, and a broad spectrum of other lymphatic diseases.”

Rockson is the sole recipient of the U.S.’s only Professorship in Lymphatic and Venous Disorders. A trained cardiologist, Dr. Rockson established his role in lymphatic care and research nearly 25 years ago.

“In 1992, I helped to create the Center here at Stanford for Lymphatic and Venous Disorders and in 1997, I took over the directorship,” says Rockson. “Fundamentally, I tried to create an academic program that simultaneously serves the goals of providing the highest level of clinical care with evidence-based medicine, creating opportunities to provide education to medical students and trainees at the post-graduate level, and serving as a platform for research. I conduct research clinically on the patient population that we see in the Center. I also have a bench lab in which I have created, and work with, animal models of lymphatic disease. I have used the laboratory as a discovery platform to then bring the research to the clinical arena. Based on these activities, in 2008 Stanford University created an endowed chair to recognize my work.

“My professorship recognizes the role of my position both in lymphatic medical care as well as research. This is an exciting opportunity because the Chair carries a defined financial budget. It has allowed me to fund some of my own research, as lymphatic research has been historically difficult to fund through the usual sources—although the situation is getting better.

As you can tell from the name of the program at the Stanford Center, we acknowledge the partnership between the lymphatics and the venous system— both of these circulations present with edema as a very important manifestation of the pathology. In the clinical practice of lymphatic medicine, both the differential diagnosis with, and treatment of, venous disease is very important. We really welcome all of these patients in order to sort out which of the problems is predominate, or when there is a combined venous and lymphatic disorder, we can deal with both components.”

Partnerships for Change

“I am now very grateful that I have been asked to join the ABVLM board” says Rockson. “My role within it will be not only to try to shape and expand the lymphatic portion of the curriculum for people that predominantly identify themselves as vein specialists, but also to use my position as a platform to develop an exportable curriculum that will embrace many of the other physician communities. We cannot expect that all of these estimated 10 million people will seek out a lymphatic specialist or a vein specialist to deal with their problems.

Most people in the U.S. obtain the majority of their care through a primary care physician, and we want to be able to reach that physician audience as well. So we’re hoping to create a curriculum that will become attractive to the generalist; over time, it can be anticipated that there will be enough social pressure on practitioners that they feel compelled to embrace and learn this curriculum, so they can take care of their patients.

“I think the obstacles for the lymphatic curriculum have been magnified by the fact that diagnostic and therapeutic choices, while they exist, have not been nearly as broad as they are in many other areas of medicine. It becomes less attractive to a clinician to embrace this area when the physician can’t use the typical model of ‘if I do X test, I prescribe Y medicine for a positive result.’ It’s not quite that simple with lymphatic diseases.

“The second impediment is that there has been an implied wish on the part of cancer specialists to deny their active role in creating LE, despite the fact that acquired LE is certainly not entirely preventable. So, rather than choosing to acknowledge that the treatment of breast cancer or cervical cancer has a high likelihood of engendering LE as a predictable sequelae, they have simply chosen to a public stance that LE is rare, that it no longer occurs, and ‘it never happens to my patients.’

"There has been a failure to recognize the high prevalence of LE. The disease is simply defined as a non-problem by those clinicians most highly associated with its incidence. This, of course, discourages the generalists from getting actively involved as well.”

So is there any hope for the future?

“There is a lot of movement now,” Rockson says. “The American Society of Breast Surgeons is openly embracing LE and acknowledging that breast surgeons need to know more about it. As these things begin to change, it becomes more important to take care of this patient population.”

Dr. Rockson currently has numerous goals for the future of lymphatics. “I’m looking for preventative strategies to become much more commonly employed so that we can mobilize to treat earlier stages of the disease and limit both its progression and severity. Educational efforts to try to minimize risk in the surgical arena are important as well.

“We need ever-improving diagnostic techniques that include better imaging capabilities. While they certainly are on the rise, we want to see them become more sophisticated than those currently available. In concert, there has been some very nice early work in the development of biomarkers and other more standard types of blood test-based evaluation for disease severity and disease presence. I think this is going to be increasingly important.”

There is much to look forward to. Rockson says, “I am very excited about the developments in my own research that are leading to the prospects for effective drug therapies to treat LE, moving away from purely physical treatments and embracing more conventional, molecular-based approaches to containing disease. I’m excited about the advanced and improving prospects for surgical interventions as well.

“And then finally, for the primary LE group, there have been tremendous strides in the last ten years in the comprehension of lymphatic vascular development and genetic contributions, thereby improving our ability to identify the absolute targets of disease—the gene mutations that cause these primary LEs. We probably only understand, at best, ten percent of them, but this is going to improve with time, leading to very specific treatments for these categories of patients.”

The Bates Difference

Kathy Bates has been LE&RN’s spokesperson for three years, receiving multiple awards for her active role in changing the image of LE by not only putting her own face to the name (or acronym), but also bringing to light the true heroes of the LE community and making their stories known.

As a patient battling secondary LE resulting from breast cancer surgery, Bates is an ambassador and hero to all LE patients. As Repicci says, “When Kathy Bates goes on CBS Sunday Morning and six million people view an episode where she is talking about LE and is shown in her doctor’s office getting therapy for it, now you begin to really broaden the knowledge base of the population at large. If you want to create change, you need a critical mass of people out there to recognize that something is a priority and to fight for it.”

Bates’ dedication to creating awareness and education in lymphatic disease is truly commendable.In fact, she often rearranges her work schedule in order to accommodate educational summits, such as the ACP meeting last November, where she finds her best opportunities to make a difference.

“I feel that the meeting went well but I exceeded my 10 minute speaking limit by quite a bit because I am so passionate about this cause,” says Bates. “I should probably take this moment to apologize for that!”

“With Kathy presenting at the ACP meeting, a symposium topic like lymphatics that may have been attended by a relatively small audience as one of many concurrent sessions, instead got several hundred physician attendees interested in hearing what she had to say. As a result, they were also introduced to presentations by the revered panel of lymphatic experts that followed her. When information is shared, bridges are built and common interests emerge,” Repicci noted.

I asked Bates to give some perspective as a patient herself. What would she change—short of eliminating the disease from existence—with regards to lymphatic disease and treatment?

“Of course my magic wand would be for obliterating the disease all together, but since you won’t give me that option, I would wave my wand for education,” Bates says. “Ten million Americans suffer from LE. That’s more than MS, Muscular Dystrophy, ALS, Parkinson’s and AIDS combined! Yet, incredibly, in four years of medical school doctors spend, in aggregate, between 15 and 30 minutes on the lymphatic system. Without education, how can those doctors properly diagnose LE? Patients continue to suffer needlessly, and as the disease progresses, it becomes even more difficult to reverse.”

Her wand must be working because she has helped make a difference in many lives.

“Over the last three years, people who suffer have gone from being mere statistics to becoming real people,” Bates says. “They have created their own LE&RN chapters here in the U.S., Canada, Europe and India. The new chapters are creating awareness and they’re working hard to raise funds for research. Having the opportunity to receive the Isadore Rosenfeld Impact on Public Opinion Award from Research!America has me very excited because I get to meet some of the people who are making a real difference with research.”

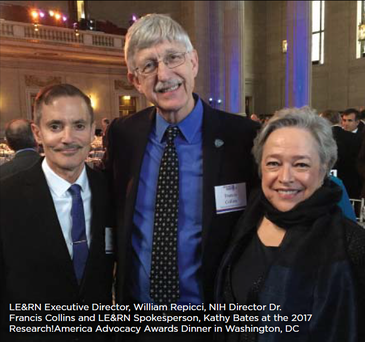

On March 15, Research!America honored Kathy Bates with the Isadore Rosenfeld Award for Impact on Public Opinion. That same night, Research!America honored Senator Lamar Alexander (TN), who is on the House Appropriations committee. “This is great news because we have a $70 million appropriation request that Senators Gillibrand and Schumer have submitted for lymphatic research at the NIH,” says Repicci.

“At the Research!America reception, Kathy and I had the chance to bring our story to Dr. Francis Collins (Director of NIH), Dr. Anthony Fauci (Director of NIAID), former Vice President Joe Biden and so many others with the power to institute change in policy and research. As the message spreads, I think there is great reason for optimism that positive change will follow.”

For more information about LE&RN and its activities, visit the website here.