By Thomas Wakefield, MD, Andrea Obi, MD and Danielle Sutzko, MD

The Vascular Quality Initiative Varicose Vein Registry (VQI VVR) was established to improve patient care in the current era of treatment of varicose veins and venous insufficiency. This registry is a collaboration between the American Venous Forum (AVF) and the Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS) Patient Safety Organization (PSO). The VQI, which launched in 2011, is designed to improve the quality, safety, effectiveness, and cost of vascular health care. The VQI includes a web-based data registry with real-time reporting, allowing physicians and centers to compare their results, processes of care, and outcomes with other physicians and centers (in an anonymous way).

- The following features distinguish the VQI from other registries and are its strengths and advantages:

- It is housed within a PSO, allowing it to have protection against discovery in the legal system and in legal proceedings

- Claims are audited, ensuring that all procedures are submitted, thus avoiding selection bias

- Follow-up is included up to th ree months and then up to one year, assessing both early and later results

- Centers in the VQI are organized into regional groups to discuss regional variations in practice and outcomes and to develop quality improvement projects

Currently, more than 392 hospitals and community-based practices in 46 states (and in Ontario, Canada) participate in the VQI, with 17 regional groups. As of 12/01/2016, more than 337,000 procedures have been captured.

“The strengths in a professional society driven, quality improvement registry are significant. The registry on the most fundamental level is designed and driven forward by individuals with academic rigor, expertise and commitment to the scientific method.”

Although few argue the importance of statistically valid, randomized, controlled trials focused on establishing the safety and efficacy of new pharmaceuticals and medical devices, outcomes of real-world practice are increasing in scientific and practical importance. Extracting real-world data via electronic medical records (EMRs) holds considerable promise for optimum efficiency in observational research.

The VQI is built on the Pathways clinical data performance platform (M2S, Inc.), allowing users to track, measure, and analyze clinical information, promote collaboration, objectively drive decisions, and optimize performance. M2S is a health care performance management solutions company that has partnered with SVS and AVF to develop and support the VQI. VQI provides quality reporting measures so that physicians can meet upcoming MIPS/MACRA requirements in 2017, which will dramatically affect their Medicare payment in 2019.

Background and Nature of the Varicose Vein Registry

The VQI VVR is the successor to the original varicose vein registry established by the AVF.1-3 It is designed to analyzeprocedural and follow-up data, benchmark outcomes regionally and nationally for continuous improvement, and help meet Intersocietal Accreditation Commission (IAC) certification requirements for vein centers. Ultimately, this results in developing best practices to improve outcomes.

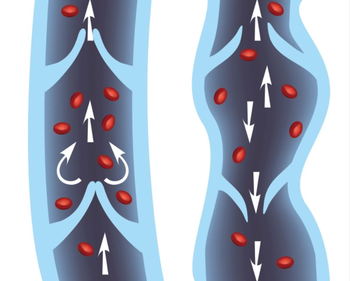

The registry captures procedures performed in vein centers, office-based practices, and ambulatory or inpatient settings. Procedures included thermal radiofrequency ablation, thermal laser ablation, mechanical ablation, chemical ablation, embolic adhesive ablation, surgical ablation and phlebectomy. Inclusion criteria include percutaneous (closed) and/or cut-down (open) procedures to ablate or remove superficial truncal veins, perforating veins or varicose vein clusters in the lower extremity (C2 or greater venous disease). Exclusion criteria include any treatment of deep veins of the lower extremity, interventions done for trauma, and treatment of C0 and C1 disease.

Some key features of the VQI VVR include the incorporation of Clinical, Etiology, Anatomy and Pathophysiology and Venous Clinical Severity Scoring classifications, as well as the inclusion of a patient-reported outcome assessment tool. Since the launch of the VQI VVR, 7,952 procedures had been included in the VQI VVR as of December 1, 2016.

Data collected from January to November 2015 in the VVR included 2664 veins in 1803 limbs of 1406 patients treated for varicose vein disease.4 The vast majority of patients entered into the registry were female and Caucasian, with nearly one-third having previously sought varicose vein treatment. Both extremities were equally affected, with one-third of patients exhibiting concomitant deep vein reflux. Axial reflux was treated almost exclusively by endovenous treatment in nearly 90% of cases (55% RFA and 34% EVLA).

Treatment of clusters was largely performed with office-based phlebectomy (85%). The average VCSS score improvement was 4.7, and patient reported outcomes of heaviness, achiness, throbbing, swelling, itching, appearance and work impact showed improvements in each area. The complete findings of this first registry analysis will be published in the Journal of Vascular Surgery: Venous and Lymphatic.

What VVR Has to Offer

Registry data offers an important avenue by which to pursue answers to relevant clinical questions. While the gold standard in clinical medicine will always remain, the well-designed randomized clinical trial (RCT), registries play an important in role in:

- Identifying the appropriate clinical question to ask by acting as a data repository

- Offering a platform by which to enable societies/individuals to engage in funding and implementation of RCTs

- Serving as an important source of data for rare or unusual diseases or outcomes that could never be studied in an RCT due to low prevalence

- Providing background data on patient characteristics and real world outcomes

“With many registries, some integration among them all makes great sense, and has been emphasized as a goal at the recent Medicare Evidence Development & Coverage Advisory Committee (MEDCAC) meeting held by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in July 2016.”

The strengths in a professional society driven, quality improvement registry are significant. The registry on the most fundamental level is designed and driven forward by individuals with academic rigor, expertise and commitment to the scientific method. Anticipated barriers to success include the need for data audits to ensure accurate and uniform reporting, and long term follow up.

Although no crystal ball is available, we predict that important questions that may be answered either from registry data alone or using the registry as a platform for RCTs/observational trials could include the following:

- The efficacy of tumescent-less (MOCA, glue) vs. thermal (RFA, EVLA) vs. foam sclerotherapy for saphenous vein ablations

- The role of perforator interruption in patients with C2-C4 disease

- The relationship of age to treatment outcomes including quality of life assessments

- Variation in indications being used for treatment of superficial venous disease across centers

- Strategies to reduce complication rates

With many registries, some integration among them all makes great sense, and has been emphasized as a goal at the recent Medicare Evidence Development & Coverage Advisory Committee (MEDCAC) meeting held by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in July 2016. As multiple registries are authored and championed by various groups, it is not feasible to think that all registries will come together and become one large registry.

Additionally, each registry has its focus and in many cases, the focus is different from registry to registry. However, what seems most important is the harmonization of core data elements, to allow interoperable extraction of data from multiple registries. With such harmonization of core data elements, aspects of the various registries may be shared, leading to greater power in the ability of registries to influence patient care and provide the information needed to optimize treatment decisions for our venous patients.

With the memory of the 2013 NIH sequestration still freshly imprinted and actively affecting surgeons and phlebologists, and decreased local/departmental funds with ever-decreasing reimbursement, registries loom large on the horizon in the current funding climate, symbolizing a new paradigm in the ever evolving arena of clinical research.5

The authors wish to thank Lowell Kabnick MD and Jack Cronenwett MD for their assistance with this editorial.

References:

- Kabnick L, Wakefield T, Almeida J, Raffetto J, McLafferty R, Pappas P, et al. Use of Compression Therapy in Patients with Chronic Venous Insufficiency Undergoing Ablation Therapy: A Report from the American Venous Registry. Journal of vascular surgery Venous and lymphatic disorders. 2013 Jan;1(1):107. PubMed PMID: 26993925.

- Lal BK, Almeida JI, Kabnick L, Wakefield TW, McLafferty RB, Pappas PJ, et al. American Venous Registry - The First National Registry for the Treatment of Varicose Veins. Journal of vascular surgery Venous and lymphatic disorders. 2013 Jan;1(1):105. PubMed PMID: 26993920.

- Almeida J, Kabnick L, Wakefield T, Raffetto J, McLafferty R, Pappas P, et al. Management Trends for Chronic Venous Insufficiency Across the United States: A Report from the American Venous Registry. Journal of vascular surgery Venous and lymphatic disorders. 2013 Jan;1(1):100. PubMed PMID: 26993905.

- Obi A, Sutzko DC, Almeida JI, Kabnick L, Cronenwett J, Osborne NO, Lal BK, Wakefield TW. First ten months results of the VQI varicose vein registry. Journal of vascular surgery Venous and lymphatic disorders. 2016.

- Moses H, 3rd, Dorsey ER. Biomedical research in an age of austerity. JAMA. 2012 Dec 12;308(22):2341-2. PubMed PMID: 23240142.