It has been estimated that between 10% and 20% of the adult U.S. and Western European populations have varicose veins and up to 50% of women by age 50 will have telangiectatic leg veins. The difference between varicose, reticular and telangiectatic leg veins is one of size and location. By convention, tortuous veins greater than 4-5mm in diameter are referred to as varicose, veins between 1-4 mm in diameter are referred to as reticular, and veins less than 1 mm in diameter are referred to as telangiectasia.

It has been estimated that between 10% and 20% of the adult U.S. and Western European populations have varicose veins and up to 50% of women by age 50 will have telangiectatic leg veins. The difference between varicose, reticular and telangiectatic leg veins is one of size and location. By convention, tortuous veins greater than 4-5mm in diameter are referred to as varicose, veins between 1-4 mm in diameter are referred to as reticular, and veins less than 1 mm in diameter are referred to as telangiectasia.

1. The most common misperception among treating physicians is that these unwanted veins can be treated independently from each other. While a telangiectasia can be treated without thought to its cause—always a feeding incompetent reticular vein—independent treatment will result in a higher risk of pigmentation and telangiectatic matting, as well as requiring multiple treatments.

- When one realizes that all superficial veins are interconnected and not separate entities—since the blood that flows through them must come from somewhere—they can be treated in one procedure with little, if any, adverse effects.

Pathophysiology for telangiectasia

1. The most common predisposing factors for the development of “unwanted” leg veins are:

- Family history

- Any activity or condition that increases abdominal pressure and impedes the flow of venous blood back to the heart may put strain on the veins, causing them to dilate.

- Standing for long periods of time

- Lack of exercise

- Obesity

- Constipation

- Wearing high-heel shoes that requires one to walk using the buttock muscles and not the calf or foot muscles

- Wearing tight undergarments or pants—producing a tourniquet effect on the proximal superficial veins.

- The use of estrogen and/or progesterone hormone supplementation for birth control or post-menopausal symptoms also causes a dilatation of the vein wall.

- Localized trauma—being hit with a tennis ball or other object—may initiate angiogenesis with the eruption of telangiectasia (localized trauma may also damage perforating veins, leading to an increase in blood flow from the deep to superficial circulations).

- Photodamage from the sun or other forms of radiation are also associated with an increase incidence of telangiectasia trough degradation of the elastic and collagen network surrounding telangiectasia.

- Pregnancy puts strain on veins by increasing blood volume, increasing estrogen and progesterone, and impeding blood flow through compression of the pelvic venous system.

- Age. Varicose and/or reticular veins and/or telangiectatic veins appear in 1/3 of patients before age 25 and increase in incidence with age, with 70% of us having visible cutaneous veins by age 70.

Laboratory findings and diagnosis

1. Irrespective of the underlying etiologic event leading to venous hypertension, the point of reflux, whether it is through either feeding reticular veins or an incompetent saphenofemoral junction (SFJ), must be treated first, especially if the patient is symptomatic.

- Duplex ultrasound examination takes 2-5 minutes and determines if the great saphenous vein (GSV) is abnormal with a reversal of blood flow.

- The duplex ultrasound is much easier to master than the stethoscope and should be used by any physician who treats unwanted leg veins. A complete discussion on the relative merits of each technique is found elsewhere. [1]

Treatment

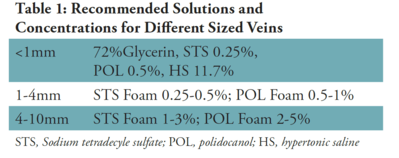

1. Sclerotherapy is a “controlled” thrombophlebitic reaction. Therefore, the main principle is to produce the least amount of inflammation. (Table 1)

- Minimizing inflammation by injecting the vessel with the minimal effective sclerosing concentration will avoid the risk of initiating new telangiectasias from forming around the edge of the treated area.

- Graduated compression immediately after sclerotherapy will minimize the resulting inflammation by decreasing thrombus formation.

2. Sclerotherapy should progress from the largest to smallest vessels. This will allow canulation and infusion of the sclerosing solution to occur most easily.

- Oftentimes, with injection of larger reticular veins, first solution is seen entering telangiectasia, which they feed into, thus obviating the need to cannulate the distal smaller telangiectasia.

3. The quantity of solution to be injected should be enough to fill the vessel and displace intravascular blood.

- When you stop seeing the solution flowing, you should stop the injection, as this means that the solution is flowing into the deeper venous system.

4. The entire venous system of each leg is treated at one time to avoid leaving areas of refluxing blood flow from causing recannalization of the treated vessel or extravasation of red blood cells from the damaged vessel, which leads to hyperpigmentation.

5. Foamed sclerosing solutions should be considered for all veins greater than 1mm in diameter.

- Can only be done with a detergent sclerosing solution such as STS(Sotradecol) or Polidocanol (Asclera). Mix 1 ml of solution with 4 ml of air.

- Foaming a sclerosing solution increases its effective sclerosing power by two, while decreasing its adverse effect profile by four since the solution is diluted four-fold by air.

6. Patients should be examined two weeks after injection so that any area of thrombosis—representing trapped blood and always called a “coagulum” to the patient—can be evacuated early through a 22- gauge needle.

- Evacuation of the coagulum will minimize the appearance of hyperpigmentation and speed resorption of the destroyed blood vessel.

7. The treated area should not be re-treated sooner than six to eight weeks after injection to allow for resolution of inflammation between treatments.

8. The patient is instructed to walk immediately after the injection session to help prevent deep vein thrombosis and constrict the superficial and perforating veins.

- Calf muscle movement produces a rapid blood flow in the deep venous system that dilutes any sclerosant that may have migrated to this area.

9. Following injection of all varicose or telangiectatic veins, the treated veins are compressed to minimize significant thrombosis.

- Graduated compression eliminates a thrombophlebitic reaction and substitutes a "sclerophlebitis" with the production of a firm fibrous cord.

- Compression, if adequate, may result in direct apposition of the treated vein walls to produce a more effective fibrosis.

- Compressing the treated vessel will decrease the extent of thrombus formation that inevitably occurs with the use of all sclerosing solutions, thus decreasing the risk for recannalization of the treated vessel.

- A decrease in the extent of thrombus formation may also decrease the incidence of post-sclerotherapy pigmentation.

- The limitation of thrombosis and phlebitic reactions may prevent the appearance of angiogenesis/telangiectatic matting

-

Finally, the function of the calf muscle pump is improved by the physiologic effect of a graduated compression stocking.

- By externally supporting untreated large veins, compression stockings will narrow vein diameter, restoring competency to its valvular function, which decreases retrograde blood flow.

- External pressure will also retard the reflux of blood from incompetent perforating veins into the superficial veins.

- Graduated compression stocking, even less than 1mm in diameter has been shown to minimize the development of post-sclerotherapy hyperpigmentation, cutaneous necrosis, and telangiectatic matting.

Microsclerotherapy

1. A two power loupe for magnification is helpful to aid visualization.

2. A 30-gauge needle is sufficient.

3. For vessels less than 1 mm in diameter, I have found that a 72% glycerin solution, mixed 2:1 with 1% lidocaine with epinephrine, is best.

- With this sclerosing solution, there is virtually no risk of ulceration, pigmentation, and telangiectatic matting.

- Resolution of the veins appears better than with a detergent solution.

Course and prognosis for telangiectasia

Unfortunately, as with any therapeutic technique, sclerotherapy carries with it a number of potential adverse sequelae and complications. Fortunately, these complications are quite rare.

Fairly common adverse sequelae include:

- Temporary perivascular cutaneous pigmentation

- Temporary flare of new perivascular telangiectasias.

Relatively rare complications include:

- Localized cutaneous necrosis

- Thrombophlebitis of the injected vessel

- Arterial injection with resultant distal necrosis

- Pulmonary emboli

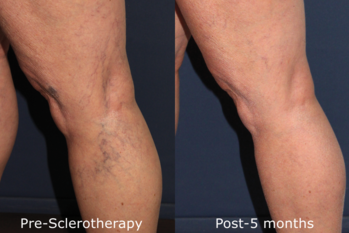

Sclerotherapy treatment of varicose and telangiectatic leg veins is a safe and effective treatment. Adverse events are rare and easily treated. A logical approach to treatment, as described above, leads to great satisfaction for both patient and physician.

- The limitation of thrombosis and phlebitic reactions may prevent the appearance of angiogenesis/telangiectatic matting.

Finally, the function of the calf muscle pump is improved by the physiologic effect of a graduated compression stocking.

- By externally supporting untreated large veins, compression stockings will narrow vein diameter, restoring competency to its valvular function, which decreases retrograde blood flow.

- External pressure will also retard the reflux of blood from incompetent perforating veins into the superficial veins.

- Graduated compression stocking, even less than 1mm in diameter has been shown to minimize the development of post-sclerotherapy hyperpigmentation, cutaneous necrosis, and telangiectatic matting.

References:

- Goldman MP, Guex JJ, Weiss RA (eds.): Sclerotherapy Treatment of Varicose and Telangiectatic Leg Veins: Diagnosis and Treatment. (5h Ed), London, 2011, Elsevier.

- Goldman MP: How to utilize compression after sclerotherapy. Dermatol Surg 2002;28:860-862.

- Goldman MP: Treatment of varicose and telangiectatic leg veins: Double blind prospective comparative trial between Aethoxysklerol and Sotradecol. Dermatol Surg 2002;28:52-55.

- Barrett JM, Allen B, Ockelford A, Goldman, MD: Microfoam Ultrasound Guided Sclerotherapy of Varicose Veins in 100 Legs Dermatol Surg 2004;30:6-12.

- Weiss RA, Sadick NS, Goldman MP, Weiss MA: Post-Sclerotherapy Compression and Its Effects on Clinical Outcome. Dermatol Surg 1999; 25:105-108.

- Leach B, Goldman MP: Comparative trial between sodium tetradecyl sulfate and glycerin in the treatment of telangiectatic leg veins. Dermatol Surg 2003;29:612-25