Clinical Practice Guidelines

Clinical Practice Guidelines

In today’s medical practice, the demand for a clinician’s time is constantly increasing, and most of this is not related to direct patient care. Simultaneously, there has been an explosion of available medical information that makes it very difficult for a physician to stay up to date or to assess the validity of implementing any of the new information into one’s current practice. Additionally, increasing bureaucratic time demands and financial restraints have decreased conference attendance for many physicians.

In this context, Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPG) were developed and defined by the Institute of Medicine as “statements that include recommendations intended to optimize patient care that are informed by a systematic review of evidence and an assessment of the benefits and harms of alternative care options.”1 A PubMed word search for clinical treatment guidelines in humans published in English during the past decade returned more than 43,000 publications. Although many of these references will not be guidelines themselves, the search reveals the increasing number of “guidelines” being published and their growing importance in medical care.

There are presently 1,904 CPGs listed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s National Guideline Clearinghouse in the past decade.2 Interestingly, there are no specific searchable categories on their website for vascular surgery, venous disease, or phlebology from which to quickly find guidelines relevant to venous disease.

Venous Practice Guidelines

For the vein care specialist, there are presently a number of resources available for finding relevant practice guidelines. The Society for Vascular Surgery has a multitude of CPGs encompassing both arterial and venous disease available on their website.3 Additionally, they developed a very useful, free smartphone application that also includes calculators for a CEAP score, the Villalta score and the Venous Clinical Severity Score for patients with chronic venous disease.4 Similarly, the European Society for Vascular Surgery has a CPG on their website published in 2015 on the management of chronic venous disease.5

The American Venous Forum and the American College of Phlebology, the two societies in the United States specifically focused on venous disease, also have guidelines available on their websites.6,7 The most clinically significant guidelines are published in leading medical journals and available free of charge (even to non-subscribers). This is done in order to encourage their implementation in practice, such as the regular updates in the treatment of venous thromboembolic disease by the American College of Chest Physicians and the SVS/AVF guidelines for the treatment of venous leg ulcers.8,9

“The publication of CPGs almost takes a life of its own. In order to incorporate the results from more recently published studies, regular updates of popular guidelines are now published every several years.”

Challenges and Limitations of Clinical Guidelines

Similar to the major increase in medical publications overall, clearly there are a large number of published guidelines, consensus reports, expert opinions and societal recommendations of which to keep abreast. Such publications may be hundreds of pages in length and incorporate more than a thousand references. Few physicians have the time to read these manuscripts in their entirety.

Indeed, an important component of many clinical conferences are presentations reviewing such guidelines and providing attendees with a summary of the important recommendations and a critical analysis of why they may or may not wish to incorporate such recommendations into their own clinical practice. The publication of CPGs almost takes a life of its own.

In order to incorporate the results from more recently published studies, regular updates of popular guidelines are now published every several years. Journals and publishers find that such guidelines significantly increase their impact factor, a measure of the frequency with which an article has been cited, and their associated stature in the publishing and advertising arena. It is implied in the titles, and by the authors and societal sponsorship of CPGs, that they are of high value and clinically useful. However, this is not invariably the case.

Clinical guidelines can in fact be limited by the quality of the literature research employed in their development, the expertise or time of the authors, and potential bias of sponsoring organizations or publications. Addressing these potential pitfalls, the Institutes of Health has defined required components in the development of clinical practice guidelines.1 These include the expectations that for guidelines to be trustworthy, they should:

- Be based on a systematic review of the existing evidence

- Be developed by a knowledgeable, multidisciplinary panel of experts and representatives from key affected groups

- Consider important patient subgroups and patient preferences, as appropriate

- Be based on an explicit and transparent process that minimizes distortions, biases, and conflicts of interest

- Provide a clear explanation of the logical relationships between alternative care options and health outcomes, and provide ratings of both the quality

- Be reconsidered and revised as appropriate when important new evidence warrants modifications or recommendations

Achieving these broad objectives is not easy. With the extensive medical literature available on most topics, the first expectation of a systematic review of the existing evidence is usually beyond most academic physicians’ availability or expertise, or even groups of individuals. Instead, most CPG efforts employ professional organizations to provide this service which ranges from $20,000 to $50,000 depending on the topic.

A final consideration for clinicians to keep in mind is that such guidelines are not meant just for them. Clinical practice guidelines are also increasingly produced for multiple purposes and end-users. Although the primary purpose of CPGs is to assist physicians to improve patient care, as explicitly stated by the American Heart Association, CPGs also serve a number of additional specific purposes:10

- Provide a synthesis of the latest clinical research

- Identify gaps in the evidence base

- Serve as a basis for development of performance measures and appropriate use criteria

- Determine whether practice follows the current evidence-based recommendations

- Reduce practice variation

- Influence health policy

- Promote efficient resource usage

Therefore, beyond quality and trustworthiness, physicians should also consider a particular CPG’s objectives (whether implicit or explicit) when evaluating its usefulness and implementation in practice.

Present Efforts for Venous Guidelines

In the context of this background, the American Venous Forum began a more structured and formal program of clinical guideline development in 2015. Under the leadership of chair Dr. Joseph Raffetto, the Guidelines and Documents Oversight Committee was established to oversee and develop specific guidelines and documents originating from within the society and from other extramural groups.

A major responsibility was to choose topics for developing AVF guidelines with its clear purpose of improving our knowledge and treatment in clinical practice. This committee would not itself develop CPGs but would choose participants for specific Writing Committees by identifying experts in the field of venous and lymphatic disease management and research.

These individuals would not be limited to society members. In addition, in order to develop the highest quality of recommendations and increase likelihood of clinical implementation, multi-specialty collaboration was specifically emphasized with participation to be encouraged from other professional organizations. In addition, a detailed policy was established to delineate rules of professionalism and business for committee members with respect to duties, responsibilities, publications and conflicts of interest.

Finally, recognizing the expense associated with systematic literature analyses, a commitment was made by the society to provide the required financial support for successful development of such guidelines.

With a focus toward answering present day needs of patients and the physicians taking care of them, four writing groups have been established to address:

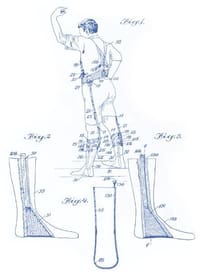

- Compression Therapy - An evaluation for CEAP Class 5 or lower disease for the requirement and duration of compression therapy before and after interventions

- Duplex Ultrasound Surveillance after Venous Ablation - Indications and timing of such surveillance particularly after endoluminal therapy

- Endothermal Heat-Induced Thrombosis (EHIT) - Review and development of a consensus EHIT classification and treatment protocol following venous ablation

- Intravascular Ultrasound (IVUS) - Recommendations for the indications and usage of IVUS in venous disease

Consistent with its established policies, representative members for the writing groups were requested and appointed from other societies, including the American College of Phlebology, Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Vascular Medicine, Society for Interventional Radiology and the International Union of Phlebology. The writing groups meet on a regular basis with working drafts now being circulated and expectations for final guidelines to become available in 2017.

An additional priority for the writing groups is for the CPGs to be focused, timely and clinically relevant. The general consensus is that exhaustive book-length analyses are not useful for practicing physicians as they are more consistent with reference works. Rather, providing actual recommendations that will prove useful for implementation into patient care practice is preferable.

Expectations for the Future

Appropriate and clinically-relevant practice guidelines will therefore be increasingly useful for clinicians and will be helpful in providing high quality care to our venous patients. Hospitals, insurers, and policy makers will also look to trustworthy evidence-based CPGs to help them in quality and outcome measurements, as well as payment/reimbursement considerations.

In these circumstances, professional societies (in a multi-specialty collaborative manner) have an important role to play in producing objective, evidence-based and clinically relevant recommendations. If they, and by extension participating members, do not take on this role, insurer or government-sponsored contracted organizations will perform this at an increasing rate. The products of such efforts, however well-intentioned, will inevitably be of lesser quality but may have a disproportional effect on patient care.

Finally, it is well for all of us to remember that CPGs should not be interpreted as the legal standard of care in all patients. As the word “guideline” itself implies, such documents are meant to be only guiding principles with the care given to an individual patient always being dependent on their specific medical condition, needs, the type of practice setting and available expertise.5

Furthermore, such recommendations are valid at the time they are promulgated but as technology and disease knowledge advances, any CPG can become outdated and inappropriate. Ultimately, medical care is an intimate one-to-one interaction between a single patient and a physician, and is just as much an art as it is a science, where the physician must always strive to do what is in the best interest of the patient.

“Hospitals, insurers, and policy makers will also look to trustworthy evidence-based CPGs to help them in quality and outcome measurements, as well as payment/reimbursement considerations. In these circumstances, professional societies (in a multi-specialty collaborative manner) have an important role to play in producing objective, evidence-based and clinically relevant recommendations.”

Dr. John Blebea is the Immediate Past President of the American Venous Forum and a member of its Guidelines Committee. All views and opinions expressed are those of the author and not of the University of Oklahoma nor the American Venous Forum.

References:

- Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines Consensus Report, Institute of Medicine. Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. National Academies Press: Washington, D.C., 2011.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. National Guideline Clearinghouse: Practice Guidelines. https:// www.guidelines.gov/ Accessed on November 27, 2016.

- Society for Vascular Surgery. Clinical Practice Guidelines. https://vascular.org/research-quality/ clinical-practice-documents/clinical-practiceguidelines. Accessed on November 27, 2016.

- uSquare Soft Inc. SVS iPG. https://itunes. apple.com/WebObjects/MZStore.woa/wa/viewSoftware id=1014644425&mt=8 https://play. google.com/store/apps/details?id=org.vascularweb. SVS&hl=en. Accessed on November 27, 2016.

- Clinical Practice Guidelines of the European Society for Vascular Surgery. Management of Chronic Venous Disease. http://www.ejves.com/article/S1078- 5884%2815%2900097-0/pdf Accessed on November 27, 2016.

- American Venous Forum. Clinical Practice Guidelines. http://veinforum.org/medical-and-allied-healthprofessionals/ guidelines.html Accessed on November 27, 2016.

- American College of Phlebology. Clinical Guidelines. http://www.phlebology.org/member-resources/ clinical-guidelines Accessed on November 27, 2016.

- Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, Blaivas A, et al. Antithrombotic Therapy for VTE Disease: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest 2016; 149(2):315-352.

- O’Donnell TF, Passman MA, Marston WA, Ennis WJ et al. Management of Venous Leg Ulcers: Clinical Practice Guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery and the American Venous Forum. J Vasc Surg 2014;60:3S–59S.

- ACCF/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Methodology Manual and Policies. https://professional. heart.org/idc/groups/ahamah-public/@wcm/@sop/ documents/downloadable/ucm_319826.pdf Accessed on November 29, 2016.