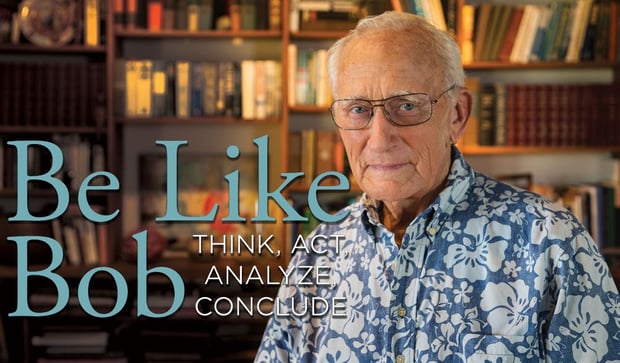

by Dan Monahan, MD & Elna Masuda, MD

Dr. Robert (Bob) Kistner is a legendary figure in venous treatment. His contributions to the field over 50 years bridge the eras between the nascency of vascular surgery and the modern practice of vein care. Dr. Kistner’s pioneering work, prolific authorship and expert presenting on venous disorders qualify his esteem, and his mentoring of young doctors exemplifies his leadership.

Dr. Kistner began his work in general surgery in 1960 and followed a path into the developing field of vascular surgery. In 1966 he became the first trained peripheral vascular surgeon in Hawaii, at the Straub Clinic & Hospital in Honolulu. The concepts and techniques developed by Dr. Kistner and his colleagues are foundational to modern vein care, and he continues to learn and lead in the venous treatment community—as a surgeon and a mentor.

Here Dr. Kistner shares his experience and knowledge with his mentees Dr. Daniel Monahan and Dr. Elna Masuda. Together they delve into topics ranging from the early emergence of venous disease treatment, modern clinical practice and the future of this ever-evolving field of medicine.

On Treating Venous Disease

Dr. Dan Monahan: When you started your practice treating varicose veins, did you follow what you learned in your general surgery residency?

Dr. Dan Monahan: When you started your practice treating varicose veins, did you follow what you learned in your general surgery residency?

Dr. Robert (Bob) Kistner: My first procedure, as a junior in externship, was to scrub in on a vein stripping, and my first operation as an intern was to scrub in on a vein stripping procedure. At that time in St. Louis, there was a man named Charles Doyle who did venous surgery. His theory was to treat venous varicose veins by taking out the great saphenous and the small saphenous in both legs.

Dr. Robert (Bob) Kistner: My first procedure, as a junior in externship, was to scrub in on a vein stripping, and my first operation as an intern was to scrub in on a vein stripping procedure. At that time in St. Louis, there was a man named Charles Doyle who did venous surgery. His theory was to treat venous varicose veins by taking out the great saphenous and the small saphenous in both legs.

There were none of the diagnostics that we have now. Zero. So he did this bilateral clean out, and the patient would stay in the hospital for a few days. His patients did very well. He had a great reputation. A lot of people didn’t buy into what he said, but that was my first exposure. So I have always had an interest in veins.

The diagnosis of varicose veins was just clinical appearance in those days—it wasn’t until the advent of the non-invasive ultrasound that diagnosis of the peripheral veins began to make any sense. We had information from tremendous clinicians through the years, Homans and those kinds of clinicians, but even they didn’t really understand the vein system, such as the function and the chronicity of varicose vein disease. That didn’t come about, I don’t think, until ultrasound opened the doors and we could actually visualize what was going on inside the veins.

Dan: When I came and stayed with you (for a month during my residency in 1987), you showed me how to do a careful high ligation. Many of the people who I see with recurrence and who have had previous vein stripping have an incomplete high ligation. The ligation has been done at the bifurcation of the anterior accessory and the GSV. These are done by vascular surgeons who have been through vascular training. Was it Doyle who taught you to do a complete high ligation?

Bob: Yes, he taught us to dissect down to the common femoral vein and ligate all of the branches. We always did that, and that was the right way as far as I was concerned. We got all the different branches and I think that was the general literature. I’m surprised by what you say you’ve seen. I am not familiar with that experience.

Dan: Have you mostly seen recurrent veins that have come from somewhere else?

Bob: I don’t have that great experience with recurrent veins from elsewhere. I know now that with lots of things that we stripped…we didn’t know where the stripper was going. When we inserted the stripper into the veins, we passed it until it got to the other end, and then cut down on it and pulled out whatever it was. Well, lots of times it was probably the accessory saphenous vein, the Giacomini or some other vein. God knows what we were pulling out because we certainly did not recognize the various routes in the thigh, and sometimes it was a great saphenous vein. So there was a lot of inexact surgery, although we thought we were being very precise by ligating all the branches of the saphenofemoral junction.

I still think we’re going to see significant recurrence in the accessory saphenous vein. I know we will. So in the next five or ten years we’re going to have to go back and close some of those veins. We’ll just have to plan on going back and cleaning those veins out. I’ve seen that myself. I’m not sure how different this will be from late treatment after vein stripping.

Dan: Yes. What do you think the number is? Say, in five years?

Bob: I don’t know what the denominator is.

Dan: But for those who you’ve closed GSVs, how many come back with anterior accessory reflux?

Bob: I don’t know the answer to that question. But we are developing data about when you close the first saphenous vein, are you doing the great saphenous or the accessory? If the accessory is leaking at the time you do the great saphenous…some people take the accessory, and some don’t… and it’s already leaking. That’s why they recur. It’s possible that axial reflux and reflux to the lower leg will develop. It’s amazing how recurrent reflux develops over time. Sometimes, the great saphenous is leaking at the same time you take the accessory. Over time, the one you’ve left in will likely develop incompetence. That’s part of the natural history of valvular reflux. So I think it’s a creeping mish-mash of things that cause recurrence. One issue is missing something that was leaking at the beginning. The second is the development of progressive disease. It just takes time.

Bob: I don’t know the answer to that question. But we are developing data about when you close the first saphenous vein, are you doing the great saphenous or the accessory? If the accessory is leaking at the time you do the great saphenous…some people take the accessory, and some don’t… and it’s already leaking. That’s why they recur. It’s possible that axial reflux and reflux to the lower leg will develop. It’s amazing how recurrent reflux develops over time. Sometimes, the great saphenous is leaking at the same time you take the accessory. Over time, the one you’ve left in will likely develop incompetence. That’s part of the natural history of valvular reflux. So I think it’s a creeping mish-mash of things that cause recurrence. One issue is missing something that was leaking at the beginning. The second is the development of progressive disease. It just takes time.

Dan: So, will we find over time that we should just do both?

Bob: Well, I don’t know. It would take another five to ten years to find out if doing so made any difference because the venous system has an enormous ability to regenerate veins in an area where you’ve taken them out. I don’t think we understand all that.

Dan: But we’re not seeing as much neovascularization with ablations?

Bob: No, not in the same way.

Dan: Should every new ablation technology have to be compared to vein stripping, or have the thermal ablations become the new gold standard?

Bob: I don’t think we can say that we know the long-term natural history of the ablation, but I think enough people keep careful records that we probably will know that. I guess that’s in the next decade.

Dan: I don’t think we know anything about what happened after stripping because we didn’t have ultrasound. We don’t know what there was. People weren’t doing venograms on their varicose vein patients.

Bob: I have to say that my honest experience with patients who have had previous vein stripping is, more often than not, their new varicose veins are developing some other way, such as through a perforator.

Dan: Pelvic?

Bob: It may be pelvic. But some other route. I always look for where the varicosities perforate, or empty into the deep system, with incompetence. I view the great saphenous vein and the small saphenous vein as just another perforator. Anatomically, that’s what they are. So if the great saphenous vein is competent, but you have an incompetent medial thigh perforator vein, then that’s just like the upper end of the GSV. That’s logical.

Dan: But treating perforators (for varicose veins) doesn’t have much enthusiasm.

Bob: I don’t think people are thinking about it that way. For some reason, I think, in general conversation, people are not really regarding the GSV and the AASV as another perforator, but I mean, what else are they?

Dan: They connect the deep system with the superficial. It’s a perforator.

Bob: That’s right. As you go down the tree, it’s just various branches that are connected into the deep veins. The lower you go, the less importance as far as axial reflux is concerned. But then the other thing is whether those perforators have functional valves or not. That’s where much of the information from Europe, the ASVAL and the CHIVA comes from. They’re looking at that direction of flow. We look at that now in our practice, all the time. If we see a return perforator, we don’t take it under normal circumstances. We leave it with some trepidation, because the condition you’re looking at, at the time of diagnosis, is one condition at one point in time. To say that’s what happens all the time, I think, is a leap of faith and it may be proven wrong.

I know one thing—seeing people with multiple duplex scans at different times, in different positions, by different sonographers, at different times of day results in a lot of variation and we don’t know why. One exam by one person, one time, is a good indication, but oftentimes might be far from the truth. It may be that if we failed to find what we needed to know, in difficult cases, we do a repeat. We have to keep asking the question if the ultrasound just doesn’t explain the clinical situation. That’s why I’m doing this thing—sourcing, and pushing here, and seeing where it comes out there, looking at reflux when sitting, standing, straining, morning, noon, night, I mean, they’re all different things.

Dan: Let’s just say, for example, you wanted to see if the way you treat varicose veins is working out. We’ve got guidelines, but there’s a lot of room for differences in those guidelines. Should I bring those patients back every year? If they’re not having a clinical issue, the insurer’s not going to pay for that clinical visit and ultrasound.

Bob: So that leads to the idea of how we do clinical practice.

Dan: If I’m going to follow all of my patients, then pretty soon my day is clogged up with follow-ups.

Bob: It gets unrealistic at some point in time. I do find day in and day out, that if I decide I need to get a piece of information about a patient’s reflux and so forth, I just do it. I don’t charge insurance in some instances if it’s inappropriate for clinical indications.

Dan: You mean you call a patient up and have them come in?

Bob: Yeah, when the patient is coming for some sort of follow-up, and I want to find out something, then I’m going to do a scan on them. Take a look, see if I was right or wrong. It’s a great luxury that you can do a non-invasive scan.

You can’t do it in a high volume situation, in many instances, where you’re working for somebody. You can’t really afford to do it over the long-term in your own practice. I’m not espousing anything. You just asked me what I did. By doing that, then I find you see things. For that reason, if you suspect something in someone you’re looking at, it’s a very good idea to take another look, do another scan at another time and see what’s going on. We know what we do is imperfect, but it’s a lot more perfect than it was. If you look back in the days before ultrasound scanning, we didn’t know what we were doing. We were doing it blindly, with the stripper—we’d pull it out the other end. So as time goes by, we’re building more accurate information, and as a result the standards are going up, and we’re talking about accessory saphenous veins and this and that. We’ll always be testing those kinds of things. We need to be testing them.

Dan: If somebody comes in with either varicose veins or other signs of more advanced venous disease, and you don’t find much during your exam, should you have them come back again? Should any of these cases require two exams?

Bob: I don’t know about that and I wouldn’t say that. But I would say if you have a good clinical impression, and it’s not explained on your first exam, to repeat the exam under some other circumstance at a different time of day, perhaps, is very reasonable. We’re treating patients and not just making rules that say if you don’t have a perforator that leads to an ulcer, then you shouldn’t treat it. I don’t believe that. That’s ridiculous. It’s a guide. For instance, there was one point where we didn’t know about one-way and two-way flow. We weren’t appreciating it, and any perforator…well, we’ve got 150 perforators. You could spend your life taking out perforators. I must say, in my time, I treated a lot of perforators that didn’t need to be treated. Certainly with things like when we go subfascially…

Bob: I don’t know about that and I wouldn’t say that. But I would say if you have a good clinical impression, and it’s not explained on your first exam, to repeat the exam under some other circumstance at a different time of day, perhaps, is very reasonable. We’re treating patients and not just making rules that say if you don’t have a perforator that leads to an ulcer, then you shouldn’t treat it. I don’t believe that. That’s ridiculous. It’s a guide. For instance, there was one point where we didn’t know about one-way and two-way flow. We weren’t appreciating it, and any perforator…well, we’ve got 150 perforators. You could spend your life taking out perforators. I must say, in my time, I treated a lot of perforators that didn’t need to be treated. Certainly with things like when we go subfascially…

Dan: The SEPS?

Bob: Subfascial SEPS. The things that we could reach were the ones that weren’t important, probably, and the ones that were important we couldn’t get to many times. We all know that.

Dan: Was Linton’s big operation unnecessary? Why did that end up giving him results that seemed like that was a good thing to do?

Bob: Those were early days. He had limited diagnostics, so he taught us a lot. He taught us that if you separate the fascia, totally, from the skin, you’ve divided every perforator there is, and years later the perforators can come back again. We know this is not a mystery because the venous system can reestablish itself. It’s a physiologic need that creates these veins that bridge the gaps.

I don’t know how you make sense of it because who’s brave enough to say they understand perforators? On the other hand, if you have a perforator at a point of great symptoms, it could be a site of pain, or it could be an ulcer, an inflammatory condition. That perforator is feeding it and it’s incompetent. You can get great results by interrupting the perforator.

Dan: It seems to me the approaches like the SEPS and the Linton procedure were more devastating, suggesting it’s better to just treat one perforator. You find the one that’s bad, and I think most of those can be treated with injection.

Bob: Yeah, be selective. I’ve gone pretty far out on that limb. I try to get the sonographer to trace the course of reflux by sourcing, looking at the directional flow and doing various augmentations and Valsalva maneuvers in various positions and at various times of the day. I think I have a pretty good understanding of what’s reflux or not in any given patient. In that case, you might have a surface vein coming down and going in a perforator, and then coming out another perforator. You can have all kinds of things in various places. I believe in my heart it is appropriate to go along those places looking for indicated interruptions.

I know in the short term if you do that, you get great results. I don’t know what happens all the time because we’re dealing with a system that can reproduce itself in many ways.

The second consideration, I think, is chronic. Chronic venous disease is a progressive, recurrent, degenerative problem, so you need a good follow up. A lot of things we attribute to a bad operation at the saphenofemoral junction because they got recurrence maybe weren’t so bad. Maybe it was just the natural history of recurrence. Five or 10 years later, the venous system can override a lot of the things that we did and were appropriate at the time they were done.

Dan: Do you think this concept of the system having the drive for regeneration is generally understood? We tend to blame recurrences on technical error, incomplete operation and other reasons.

Bob: I would question that.

Dan: Maybe it’s just inevitable.

Bob: I think so, yeah. It’s a huge learning curve. For somebody who’s going nuts over it like I have—I really care about this sort of thing—longitudinal studies over long periods of time show very dramatic things. I’ve seen many cases where there’s a little bit of reflux at the saphenofemoral junction, and maybe they’ve been treated and ablated, and subsequently there’s a little reflux in the lower leg. Five or 10 years later they can come back with connections between these veins that connect upper thigh to lower leg varices, varices that connect from one end to the other directly. I cannot understand how the body can do that, but it does. Such a patient just has to be treated at that point, and then treat them again later where the recurrence develops.

Dan: Would there have been something to do 10 years before when you just had the two isolated sources?

Bob: Ten years before, they had continuous reflux, so you did an ablation, or you did the stripping. And then 10 years later, you find varicose veins that go down the long course of the original saphenous vein and come out right at the bottom there. You’ve probably seen that.

On Treating Swelling and Inflammation/Ulcers

Dan: So you’ve said, “It’s a progressive degenerative disease.” And then you said the other important thing is that there’s this tendency for the veins to recur. Talk about the other thing you’ve been talking with me about the last few years, about this disease involving chronic inflammation.

Bob: The venous reflux itself probably does not generate ulcers until there becomes an inflammatory component. What generates that inflammatory component could be trauma, dermatitis, gout or maybe an underlying inflammatory problem. There’s evidence that reflux itself, and swelling, can generate white cell reaction and start the inflammatory cascade. I don’t think it becomes a skin disease, which is ulcer, just by reflux. But once it does get that way, then it has inflammation plus reflux and that’s a bad combination.

Dan: What we were talking about, I think, was stasis having an inflammatory component. It seems that inflammatory component, I don’t know what it’s initiated by, is there once there’s swelling. Swelling involves an inflammatory component.

Bob: Swelling is a very bad thing in the lower leg. Once it’s there, healing is impaired, sometimes prevented. What is the reason why a wound care center that only wraps the legs gets good results? To me, it’s that they get rid of the swelling. I don’t know what else it is. What’s the magic? Certainly there’s nothing magic about positively affecting venous return, although there’s some evidence that makes some kind of difference. I think the more logical thing is swelling is related to the inflammatory cascade in some way, and in order to treat the swollen inflamed leg, you must treat the swelling, you must treat the inflammation and you must ultimately, to gain permanent control, get rid of the reflux so it doesn’t keep repeating itself. Anyway, that’s what I try to do.

Dan: I think that’s one thing, emphasis on the inflammatory aspect—I see people who are referred for swelling and they don’t have venous disease. A lot of people with atrial fibrillation have some mild to moderate swelling—people with prior knee replacements, obese people who don’t have venous disease. I put them all in stockings. Those people aren’t put in stockings until they make their way to me, yet they all have leg swelling. It seems to me it would be beneficial, no matter what the source of the swelling is, to try to keep them compressed to minimize the swelling and the progression to more stasis changes.

Bob: Sure, I agree. How many people are referred with lymphedema? What is lymphedema? We all know congenital lymphedema is a pretty big, nasty thing, but that’s not what I’m talking about. I’m talking about edema and venous disease, and the lymphatic component. So where is the water—the circulation filtrates out the water, becomes protein rich, call it lymph, and that goes back by way of lymphatics, probably, rather than the venous system. We used to think it went back in the venous end of the capillary. Now we think it goes back through the lymphatics—there are gallons of it each day and more so if something goes wrong with that mechanism— then you get chronic swelling and you can get into real trouble with dermatitis, etc. that leads to ulcers.

Dan: It seems to chronically progress—the swelling begets swelling. It’s almost as if the swelling continues to compress the lymphatics more and more, then that makes the swelling worse, and it compresses it more, but at some point, where does that compression turn into actual damage or destruction?

Bob: I think that’s inflammation.

Dr. Elna Masuda: It seems that the venous system and the lymphatics are very closely linked by the fact that when venous hypertension is present, it leads to swelling that can sometimes look like lymphedema, even by ultrasound. That swelling is fluid collecting within the soft tissue, let’s say from a venous obstruction, and that fluid must make its way back to the central system, and it has to return to the heart, either by venous or by lymphatic routes. What happens then is that the fluid overloads the lymphatic system and it can’t compensate for the veins that are not working, and then suddenly you’ve got a combination of venous hypertension, swelling and then associated lymphedema.

Dr. Elna Masuda: It seems that the venous system and the lymphatics are very closely linked by the fact that when venous hypertension is present, it leads to swelling that can sometimes look like lymphedema, even by ultrasound. That swelling is fluid collecting within the soft tissue, let’s say from a venous obstruction, and that fluid must make its way back to the central system, and it has to return to the heart, either by venous or by lymphatic routes. What happens then is that the fluid overloads the lymphatic system and it can’t compensate for the veins that are not working, and then suddenly you’ve got a combination of venous hypertension, swelling and then associated lymphedema.

Bob: I think another question relates to the obese person who has elevated venous pressure. Do they also have elevated lymphatic pressure? I don’t know any data but I think they probably do. It allows you to have something where you think you understand it anyway. You’ve really got to treat that edema to control the inflammation. You’ve got to control the edema, as one begets the other. As you say, to not treat the edema begets the inflammation. Is that what you’re saying?

Dan: I think that’s the case. When you started telling me about treating acute inflammation with Triamcinolone and Saran Wrap, we started doing that, and now I see these people with lymphedema, and they’ve had multiple episodes of cellulitis, or they’ve been put in a hospital, and they’ve been put on antibiotics, and it quickly gets better and they’re sent home on a whole lot of antibiotics. Finally, I get to see them, and I think they have some kind of acute inflammatory flare and I treat that, because they don’t have fever, or high white blood cell count—they don’t have other signs of infection. It’s just their lower leg is red, and I treat them with the Triamcinolone and it gets better.

Bob: Well, I call that congestive cellulitis now.

Dan: Just getting them off their feet to bed rest seems to be what helps. So I’m wondering, how much of the cellulitic episodes were a complete waste of antibiotics?

Bob: A lot, a lot. The way I do it, in my office I have a tilt table. I put them on the tilt table and I raise the leg up, and all of a sudden the water starts to drain out, and the inflammation goes away, and the pain, I mean right in front of your eyes, goes away. Then you look at their venous system. It may or may not be abnormal. So, you’ve got venous disease. You’ve got lymphatic disease. You’ve got swelling and the inflammatory cascade. This is a fairly complex disease.

Elna: Bob, you’ve never backed down from a complex case, and you’ve approached them all with true scientific rigor. Your contributions are enormous and that’s why we chose you for this Mentors Who Made Me installment. We’ve been lucky to learn from you first hand and we thank you for continuing to share your wisdom with the vein community.

Mentors & Mentees

Dan: I was introduced to Bob Kistner after I graduated from high school. He invited me to tag along with him during my summers off in college. I worked with him for three summers then went to medical school, and eventually a surgery residency, all because of his influence, touching base with him all along the way. He was a mentor, not just in the science of medicine, but by modeling for me what it is to be a surgeon. After my training, I continued to visit him periodically and he continued to mentor me in treating venous disease specifically. So, that’s why I am where I am today.

Dan: I was introduced to Bob Kistner after I graduated from high school. He invited me to tag along with him during my summers off in college. I worked with him for three summers then went to medical school, and eventually a surgery residency, all because of his influence, touching base with him all along the way. He was a mentor, not just in the science of medicine, but by modeling for me what it is to be a surgeon. After my training, I continued to visit him periodically and he continued to mentor me in treating venous disease specifically. So, that’s why I am where I am today.

Elna: I thought general surgery was my destiny until I met Dr. Robert L. Kistner and my whole world changed. As a second year resident in Honolulu Hawai’i, he showed me that venous disease was under recognized and under treated. He educated me on things I had never learned through medical school. It was through his innovative, determined, thoughtful and insightful diagnosis and treatment of veins that I realized that venous disease was very important for the patient, and intellectually interesting and gratifying for me. His inspiring teaching and spirit has been felt around the world, and I have had the privilege of a lifetime to have been part of his world.

Bob: Elna and Bob are both individuals who have helped me learn a lot more than they ever learned from me, so the credit for their success goes to them—and the credit for my success lies in the minds and challenges of the younger and brighter people who have worked with me through the decades, of which Dan and Elna have both been a major source. -Robert Kistner, MD

The West Coast Vein Forum

The West Coast Vein Forum will be held September 8-10, 2017 in Olympic Valley, California. Dr. Kistner, Dr. Masuda and Dr. Monahan will be speakers at the meeting. All are welcome.

See the American Venous Forum website for registration information.