Do we need venous specialists?

Do we need venous specialists?

Before we consider the need for and the value of standardized training and certification in venous and lymphatic medicine (VLM), we ought to ask a fundamental question: Do we need venous specialists? This is precisely the question Mark Meissner asked during his outstanding keynote presentation, Venous Disease: Where are We Going, which he delivered at the ACP Annual Congress in November 2015.[1]

He noted the large patient population, significant technological advances over the past 15 years, and patients grateful for effective and minimally-invasive treatments. It was concluded, “Yes, we definitely need venous specialists.” But Dr. Meissner also noted that training in venous disease, both from a cognitive as well as from a procedural standpoint, is often inadequate, stating that “currently there are very few training opportunities that really encompass the entire spectrum of venous disease.” He established that the “focus of our efforts in the future should probably be on developing a standardly-trained venous specialist.”

Current training in VLM

Is Dr. Meissner right? There is evidence to suggest that current approaches to training are not sufficient. Most dermatology programs include procedural experience with sclerotherapy, lasers, tumescent anesthesia, and wound care, but program requirements require only didactic sessions for “invasive vein therapies.”[2] Most programs offer little to nothing regarding duplex ultrasound, venous thromboembolism and other aspects of venous disease.

A SIR Task Force on training requirements in interventional radiology (IR) noted inconsistencies in time on service, clinical training, and procedural experience have led to a wide variation in the knowledge base and technical skill of IR fellowship trainees.[3] Standard IR training covers a range of procedures, but does not include sclerotherapy, compression, phlebectomy, or endovenous thermal ablation. The Task Force stated that advanced competencies and interventions in recently developed service lines, such as venous disease, would require significant additional clinical and procedural experience

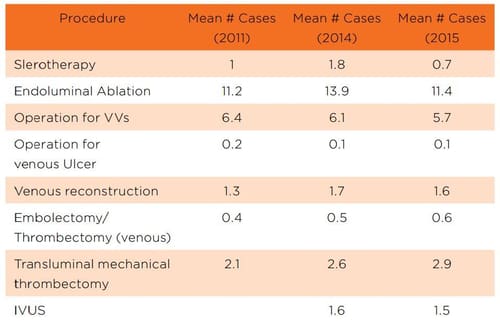

There is evidence that current training opportunities in vascular surgery are also inadequate. Displayed in Table 1, the average vascular surgery trainee completes training having done almost no sclerotherapy, fewer than 15 endovenous ablations, about six open surgeries, and has had a surprisingly inadequate experience in deep venous procedures.[4] The trend over the last several years shows no improvement in these numbers.

“Education is at the core of what physicians do. An important question is how to assure physicians obtain comprehensive training in venous and lymphatic medicine so that patients receive care from clinicians who are well-trained.”

Table 1: ACGME Case Logs: Vascular Surgery

If we examine real-world data reported at the February 2016 meeting of the American Venous Forum regarding the Vascular Quality Initiative Varicose Vein Registry from 50 centers on 1406 patients (1803 limbs), nearly 20% of venous insufficiency treatments were done under general anesthesia, and foam sclerotherapy was utilized in < 1% of patients.[5] Standardized and improved training might lead to reduced use of general anesthesia and increased use of foam sclerotherapy—an effective technique.

Dr. Meissner reviewed a year of University of Washington experience (5/13-5/14) involving patients with complex chronic iliocaval occlusion. They treated 26 patients with a successful crossing in 92%, but noted that 19% of the patients had prior intervention.

Their analysis suggested 100% of these cases were preventable and that a reason for why the stenting went wrong could always be identified, including improper stent selection or sizing, improper overlap, or failure to stent all disease. It is likely that these failures could be avoided with good training.Thus, we can conclude training in VLM is generally inadequate.

Establishing VLM Educational Standards

Education is at the core of what physicians do. An important question is how to assure physicians obtain comprehensive training in venous and lymphatic medicine so that patients receive care from clinicians who are well-trained. One of the goals the ABVLM established at its outset in 2007 was to establish educational standards for teaching and training programs in VLM.

A curriculum is the backbone of standardized education, and a curriculum is built around an understanding of the content of the field. There is a distinction between core content and a curriculum. Core content defines the boundaries of the discipline, outlines the areas of knowledge considered essential, and provides a framework for development of a curriculum.

A curriculum is an operational process by which core content is integrated into the academic elements of an educational program. With this in mind, the ABVLM embarked upon a three-step collaborative, multi-specialty consensus process to establish educational standards for venous and lymphatic medicine.

Core Content: Step One

The first step involved development of a consensus-driven, multi-specialty based core content. The “Core Content for Training in Venous and Lymphatic Medicine,” endorsed by the ACP and the AVF, was published in Phlebology in October 2014.[6] (See Figure 1). The Core Content Task Force was comprised of highly regarded leaders from dermatology, interventional radiology, phlebology, vascular medicine, and vascular surgery. Input was also obtained from numerous other experts in venous and lymphatic medicine from around the world.

Figure 1: The core content for training in venous and lymphatic medicine is organized around five key areas.

“Comprehensive program requirements or institutional requirements for physicians who wish to specialize in the care of patients with venous and lymphatic disorders are conspicuously absent.”

Program Requirements: Step Two

Program requirements identify knowledge and skills that must be mastered during training, and serve as a guide for a one-year fellowship training program. It delineates the requirements regarding program director, faculty, institution, facilities, resources, educational program, and training environments.

While program requirements provide guidance about the kinds of experiences fellows should have, they allow flexibility in how programs structure these experiences. There is a difference between knowledge of therapeutics and procedural/technical skills. A program requirements document defines which areas require knowledge and which require procedural/technical skills.

It is well-recognized the pathway to venous and lymphatic specialization is diverse, and there is no commonly accepted format for physician education and training along that path. Comprehensive program requirements or institutional requirements for physicians who wish to specialize in the care of patients with venous and lymphatic disorders are conspicuously absent.

The development of the “Program Requirements for Fellowship Education in Venous and Lymphatic Medicine,” recently approved for publication in Phlebology,[7] reflects the work of experts from specialties including cardiology/ interventional cardiology, dermatology, family medicine, interventional radiology, vascular medicine, and vascular surgery. This document’s format follows that and is used by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) for all ACGME-approved programs.

Curriculum Implementation: Step Three

Step three involves implementation of the core content and program requirements into educational programs in the area of VLM. The ABVLM, in order to promote and support the development of these one-year fellowship programs, has created a Fellowship Accreditation and Oversight (A&O) Committee and a Fellowship Development Committee.

The ABVLM A&O Committee, chaired by Dr. Mark Meissner, has:

- Developed an application process and materials

- Created and implemented an application review process

- Designed oversight processes and procedures

The ACP has been utilizing a similar process for their fellowship program, and this will transition to the ABVLM. The ABVLM Fellowship Development Committee, chaired by Dr. Steve Zimmet, is focusing on promotion and development of fellowship programs, with the goal of fostering interest in offering fellowships and providing information and resources to potential program directors (PDs) and programs.

The committee will develop a list of potential program directors and institutions, and anticipates hosting face-to-face meetings with potential PDs. The committee has begun development of a toolkit to assist PDs, with topics to include:

a. How to delineate the value of VLM fellowships

b. Why start a program?

c. Overview of the program requirements

d. Understanding the required steps

e. Enlisting departmental and institutional support

f. Information and resources regarding funding options

g. Fellow appointments (attracting high-quality candidates)

Why Develop Venous and Lymphatic Fellowships?

Comprehensive VLM education is the key to producing competent providers. This education is not currently available in any one discipline. This gap suggests the need for standardized training.

The ABVLM believes there are vitally important educational and health care system benefits that would occur if one-year fellowship programs in venous and lymphatic medicine were developed.

“The committee will develop a list of potential program directors and institutions, and anticipates hosting face-to-face meetings with potential PDs. The committee has begun development of a toolkit to assist PDs…”

Fellowships would:

- Standardize training

- Graduate better educated physicians

- Foster academic development

a. Young physicians can be a stimulus for scientific inquiry

b. Development of future faculty

c. Development of future leaders - Improve the health care system

- Improve patient care

In addition, such programs would likely significantly impact visibility, representation, acceptance, and recognition of the field.

American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) Recognition: Brief Overview

There are three types of ABMS-recognized boards: primary, conjoint, and subspecialty. Simply put, phlebology will not be recognized as a primary specialty. It’s been 25 years since the ABMS recognized a new primary specialty, which was the American Board of Genetics and Genomics.

Conjoint boards are essentially of historical interest, with the only example being the American Board of Allergy and Immunology. This said, there are over 120 ABMS recognized subspecialties, with the latest being Addiction Medicine in October 2015. If recognized, VLM would certainly be a subspecialty of various primary boards.

Fellowships and Specialty Recognition

It is important to recognize no specialty or board was ABMS-recognized at its inception, and the path to such recognition is typically long and very political. It is instructive to look at recent examples of free-standing non-ABMS boards that became ABMS-recognized. Table 2 compares looks at three specialties that have recently become ABMS-recognized (Addiction Medicine, Hospice & Palliative Medicine, and Sleep Medicine), and two that are free-standing (Vascular Medicine, VLM). The table lists:

- The number of years between AMA recognition of the field and ABMS recognition for those specialties now ABMS-recognized, or simply the number of years since AMA recognition for those not currently recognized

- Membership at the time of ABMS recognition or currently

- Years since the first certification exam was delivered at the time of ABMS recognition or currently

- Fellowships in place at the time of ABMS recognition or currently

Table 2: Comparison of selected subspecialties at the time of ABMS recognition (Yellow) vs. not currently recognized (Green)

A review of this data suggests VLM is early in the process, with the most obvious “deficit” being the number of fellowships.

The Certification Process and Exam

Another important question is how best to establish a threshold of knowledge and competence in treating venous and lymphatic disorders so clinicians may strive to exceed that threshold and patients may recognize those who have done so.

We know adequate knowledge is essential to the development of medical expertise and effective clinical decision-making. Given the fact physicians from many different backgrounds are delivering vein and lymphatic care, and that formal training in the field is generally recognized as being deficient, surely it is reasonable and useful to have some way of identifying those who possess a foundation of knowledge and experience in the management of venous and lymphatic disease. Unfortunately, existing specialty board exams do not achieve this goal.

The value of certification comes from assessing a clinician’s training and from establishing a formal measure of a clinician’s knowledge base. There is also value in the knowledge gained by the candidate in preparing for the examination. The ABVLM certification exam is open to U.S. and Canadian physicians, with full and unrestricted licenses to those who also meet the residency, fellowship, or experience track requirements. These requirements are available on the ABVLM website.

In order to be fully recognized, a field must have both appropriate educational standards and training opportunities, as well as a way to establish a threshold of knowledge and competence. We hope the ABVLM initiatives will help further the goal of improving the quality of physicians practicing in the field, increase the recognition and credibility of the field, ultimately leading to better patient care.

“There are three types of ABMS-recognized boards: primary, conjoint, and subspecialty. Simply put, phlebology will not be recognized as a primary specialty.”

ABVLM: What is the Value?

We believe there are compelling visionary reasons to support the ABVLM and its mission. We recognize current training is not sufficient and that the future of the field will be greatly impacted by whether standardized training is developed or not. Regarding recognition, it is critical to demonstrate physician commitment to the field.

Becoming a diplomate is a concrete demonstration of interest in the field and the willingness of physicians to accept a certification process. Boards such as the ABVLM have often been a precursor to an ABMS-recognized subspecialty board, with Addiction Medicine, Sleep Medicine, and Hospice and Palliative Medicine as recent examples.

When the field of VLM has achieved better recognition, significant benefits will occur in the areas of insurance reimbursement and advocacy.

One can also easily make the case ABVLM adds value from a strictly business perspective. The financial costs of ABVLM certification would be recovered if a physician has a single patient come to their practice as a result of their diplomate status. There are several sources where patients can be made aware that you are an ABVLM diplomate, including the ABVLM and your own website. It’s not hard to imagine a patient in your geographic location is searching the ACP website for a vein physician.

Such searches would likely produce a number of physicians listed, but relatively few with ABVLM diplomate status. It is also easy to anticipate this status could factor into their decision of whom to schedule a consultation. In a consumer survey in 2010 of more than 1,000 randomly-selected U.S. adults, 91% listed board certification as an important factor when selecting a physician.[8] VLM practitioners can educate patients about what it means to be an ABVLM diplomate by providing ABVLM patient information brochures. Educated patients may refer friends who are looking for VLM services.

It is the mission of the American Board of Venous & Lymphatic Medicine “to improve the quality of medical practitioners and the care of patients related to venous disorders through rigorous testing, reliable certification, and improved educational standards.” Vetted by a stringent psychometric analysis, the ABVLM has created what we believe is the most comprehensive and properly constructed and scored VLM examination in the world.

The ABVLM has used a collaborative consensus process to develop the most thorough and up-to-date core content and program requirements documents in existence. These serve as the foundation from which one-year fellowships can be created. These initiatives will naturally lead to more knowledgeable practitioners and pave the way towards the VLM specialist of the future, a physician with a level of training that simply does not exist today.

This is the best way to ensure patients receive quality care from physicians well-trained in the field. Our commitment to medical professionalism demands nothing less.

Conclusions

The fate of a specialty ultimately depends on its acceptance by the medical community. VLM has many of the attributes associated with a true subspecialty. There have been major advancements in the diagnosis and treatment of venous disease. Venous medical societies exist around the world. A growing number of conferences are devoted to venous and lymphatic disease, and there are multiple journals dedicated to venous and lymphatic medicine.

However, it is time to strengthen and standardize venous and lymphatic curricula and training in order to develop qualified comprehensive specialists. In addition, given that many physicians from various backgrounds are delivering treatment for patients with venous and lymphatic disorders, and current training is inadequate regardless of primary specialty, it is reasonable to have a method to assess foundational knowledge. The ABVLM is working to fill this gap.

“Given the fact physicians from many different backgrounds are delivering vein and lymphatic care, and that formal training in the field is generally recognized as being deficient, surely it is reasonable and useful to have some way of identifying those who possess a foundation of knowledge and experience in the management of venous and lymphatic disease.”

To advance knowledge, skills, and outcomes in a meaningful way, we must think long-term, with the objective to improve venous training via the creation of fellowship training programs. We believe this is critical to achieving true subspecialty status, and that we will remain an “interest” group if we don’t.

- Meissner M. Venous Disease: Where are we Going?,” keynote presented at the 29th Annual Congress of the American College of Phlebology, Orlando, Florida, November 2015.

- ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Dermatology. https://www.acgme.org/ Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/080_ dermatology_2016.pdf. Accessed July 9, 2016.

- Siragusa DA, Cardella JF, Hieb RA, et al. Requirements for training in interventional radiology. JVIR 2013;24(11);1609–1612.

- Vascular Surgery Case Logs National Data Report, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, prepared by the Prepared by: Department of Applications and Data Analysis. Available at: https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/ SurgeryVascular_National_Report_Program_Version. pdf. Accessed May 15, 2015.

- Almeida JA et al. VQI varicose vein registry. Presented at the 28th Annual Meeting of the American Venous Forum, Orlando, Florida, February 2016.

- Zimmet SE, Min RJ, Comerota AJ et al. Core content for training in venous and lymphatic medicine. Phlebology. 2014 Oct;29(9):587-93.

- Comerota, AJ, Min RJ, Rathbun SW, et al. Program requirements for fellowship education in venous and lymphatic medicine. Accepted for publication in Phlebology, July 20, 2016.

- ABMS commissioned consumer survey conducted by the Opinion Research Corporation, Princeton, NJ, December 2010. http://www.abms.org/media/1210/ abms_consumer_survey_fact_sheet_4-2011_final.pdf. Accessed July 21, 2016.