A 48-year-old morbidly obese patient presents with a 10-year history of slowly progressive bilateral leg swelling with unusual skin changes (figure 1). His calves, ankles, feet, and toes are markedly indurated and swollen yet his mid and distal calves display a mild concavity suggesting subcutaneous atrophy. Confluent verrucous papules overlie the distal calves with associated hyperpigmentation. Does he have chronic venous insufficiency, lymphedema, or both disorders?

Figure 1: Patient with swollen legs, described in the manuscript.

Patients with swelling due to lymphatic disorders often encounter significant obstacles to appropriate diagnosis and treatment. Many clinical sources that discuss leg swelling do not even contemplate lymphedema as a possible diagnosis. Despite the lymphatic system assuming a crucial role in overall health and that tremendous progress in lymphatic research has been achieved over the last two decades, the subject of lymphatic impairment continues to be relatively neglected by the medical profession. Lymphedema is much more prevalent than is generally recognized by physicians, and is unfortunately often under-diagnosed or misdiagnosed resulting in inadequate treatment or no treatment.1,2 Vascular physicians have a unique opportunity to provide needed care to these underserved patients.

Definition, Pathophysiology and Classification

Lymphedema is a chronic, progressive condition in which impairment of the lymphatic vasculature results in excessive, sustained accumulation of protein-rich fluid in the interstitial tissue, leading to a pathological increase in subcutaneous tissues, damage to skin, fibrosis, increased risk of infection, interference with wound healing, significant disability and marked psychosocial impairment.3,4 Lymphedema most commonly involves the limbs but can also affect the genitals, trunk, head and neck. Pathophysiologically, lymphedema results from a:

- Dynamic insufficiency, or “high output lymphatic failure,” in which the lymph filtrate exceeds or overwhelms the transport capacity of an intact lymphatic system (e.g., lymphedema that accompanies venous hypertension, congestive heart failure, tricuspid regurgitation, etc.);

- Mechanical insufficiency, or “low output lymphatic failure,” which occurs due to paralysis, inadequacy, orobstruction of the lymph vessels secondary to trauma, radiation, surgery, or underdeveloped lymphatics. In this scenario, a normal lymphatic load cannot be effectively processed by the dysfunctional lymphatics (e.g., lymphadenectomy, primary lymphedema);

- Combined insufficiency, or a composite of the two (chronic venous insufficiency [CVI ] is a classic example whereby both an excessive lymphatic filtrate and inflammatory associated lymphatic obstruction eventuate in clinical lymphedema).

Traditionally, lymphedema classification schemes have exclusively labeled affected patients with either a primary or secondary cause. Primary lymphedema due to a congenital malformation or dysplasia was considered rare, whereas the secondary type associated with cancer treatment (lymph node dissection, radiation therapy), trauma or infection was significantly more common. However such classification is simplistic and becoming obsolete as mounting research demonstrates that genetic mutations can lead to both primary and secondary lymphedema.5,6 While there remains a classification continuum wherein primary lymphatic disorders (Milroy disease) reside at one end and true secondary lymphedema (filariasis) at the other, evolving data suggests that minor or moderate genetic defects of the lymphatics occur more frequently than previously understood and as a result, the line between primary and secondary lymphedema will progressively blur.7

Lymphatic Vasculature Function

Recalling the important and sometimes overlooked functions of the lymphatic vasculature is necessary to bolster interest and understanding of lymphedema and to facilitate effective treatment. The lymphatic system plays a fundamental role in maintaining health through fluid homeostasis, regulation of immunity, and digestion.

Lymphatic vasculature consists of a series of vessels, lymph nodes and lymphatic organs (spleen, thymus) that act as a drainage system connecting interstitial spaces to the central circulation. As blood moves through the circulatory system, approximately 10% of the fluid filtered by blood capillaries becomes trapped in interstitial tissues along with vital proteins. In contrast to blood capillaries, whose structure precludes entry of large protein molecules, lymphatic vessels’ specialized structure and function facilitate entry and transport of macromolecules and accompanying fluid, returning it to the circulatory system. In addition to its role in homeostasis, the lymphatic system is instrumental in immune function through its production and transport of lymphocytes and removal of cellular debris. Further, the lymphatic vessels in the gastrointestinal lining actively participate in lipid absorption and transport.

Etiology

Lymphedema related to cancer treatment, especially breast cancer treatment, has been widely discussed in the literature and, to a relative degree, cancer-related lymphedema is recognized and treated. In contradistinction, other prevalent forms are often not recognized and therefore not adequately treated, including:

- Lymphedema secondary to advanced chronic venous insufficiency (figure 2)

- Lymphedema secondary to obesity (figure 3)

Figure 2: Evidence of coexistent chronic venous insufficiency (extensive stasis hyperpigmentation and atrophy within the distal gaiter distribution) and lymphedema (foot/toe swelling, peau d’ orange appearance along the medial calf, exaggerated skin creases and lymphostatic verrucosis) are evident in this patient with long standing leg swelling.

Figure 3: This 428 pound man displays massive disfiguring lymphedema including marked bipedal (note obscuration of the left sided toes by the overlying “buffalo hump”), calf, and thigh swelling with deep, exaggerated skin creases. Four months prior he had undergone resection and skin grafting of refractory medial calf ulceration with an adjunctive medial thighplasty. His only lymphedema risk factor was morbid obesity.

Phlebolymphedema: Lymphatic Failure in Venous Disease

Lymphedema secondary to CVI (so-called “phlebolymphedema”) is an accumulation of excess fluid in the interstitial tissues caused by a combination of interrelated venous and lymphatic dysfunction.8,9 In the presence of early venous hypertension, the lymphatic vasculature compensates by increasing lymph drainage which prohibits the development of edema. If not corrected, the excessive lymphatic water load overwhelms the transport capacity of the lymphatic vessels yielding a low protein orthostatic edema.10 In many cases, venous procedures rectify the underlying venous disorder to the point the edema sufficiently resolves. However, when venous procedures are inappropriate or are ineffective in addressing the lymphatic component of the disorder, the longstanding “high output” overload in lymph flow, often accompanied by inflammatory lymphangiothrombosis, eventuates in a traditional “low output” lymphatic system failure. Consequently, extravasation of proteins into the interstitial tissue ensues leading to a cascade of inflammation with leu kocyte migration and activation, as well as impaired capillary flow, and thrombosis resulting in cutaneous and subcutaneous fibrosis, as well as adipose deposition. By this stage, CVI has progressed with associated distinctive skin changes and worsening non-pitting swelling. This progressive constellation of manifestations is referred to as “phlebolymphedema.” Additionally, affected patients are at an increased risk of cellulitis and lymphangitis because the edema creates a culture medium for bacteria growth in the setting of regional and systemic immune dysfunction.10 Clearly the development of phlebolymphedema is associated with significant disability and morbidity. Recognition that the persistent edema in a CVI patient may actually represent concurrent lymphedema is integral to appropriate treatment.

Figure 4: Elephantiasis nostras verrucosis is exemplified within the right calf of this morbidly obese woman. A chronically draining foul smelling lymphostatic ulceration overlies the foot.

Figure 5: Massive localized lymphedema along the right distal medial thigh in a morbidly obese subject. Note the tumor like nodule overlying the large pendulous mass, or “pseudotumor.”

Lymphedema Secondary to Obesity

Obesity may be the most common cause of secondary lower extremity lymphedema in the United States. While the link between obesity and lower extremity lymphedema has not been well-documented in the medical literature, a 2008 publication documented data for approximately 15,000 patients from 17 wound centers across the U.S. and found a staggering 74% prevalence of lymphedema in morbidly obese patients.11 Another study on 21 patients with Stage III lymphedema (elephantiasis) found that all subjects were obese, with 91% (19 patients) of them fulfilling criteria for morbid obesity with an astounding average BMI of 55.8.12 A recent small study suggests that as BMI increases, there might be a threshold above which lymphatic flow becomes impaired. All patients with a BMI higher than 59 kg/m² had lymphedema, while lymphatic function was normal for all those with a BMI below 54 kg/m².13

The definitive pathophysiological link between obesity and lymphedema is unknown but various hypotheses have been discussed including structural lymphatic changes in the interstitium, impaired diaphragmatic movement, increased abdominal pressure, lymphatic obstruction due to overhanging abdominal pannus, and/or arteriovenous proliferation within oxygen demanding fat tissue without proportional lymphatic proliferation.

Extreme Presentations

An often grotesque subset of lymphedema patients present with extreme skin and vascular changes. Elephantiasis nostra verrucosa (ENV ) is an uncommon and disfiguring condition that arises as a complication of Stage III lymphedema. Synonyms include lymphostatic verrucosis and “mossy leg and foot.” Typically bilateral, and generally associated with obesity, it is characterized by profound hyperkeratosis, lichenification, and dermal fibrosis with verrucous, papillomatous, and tumor-like nodules. Large draining mephitic ulcerations can occur, as well (figure 4). The causal events in ENV are uncertain, but are likely associated with recurrent streptococcal cellulitis/lymphangitis in the setting of obesity. A vicious cycle of recurrent infection and progressive swelling ensues, eventually culminating in the classic ENV presentation.

Massive localized lymphedema (MLL) is a term used to describe the benign overgrowths of lymphatic tissue in morbidly obese patients. Sometimes referred to as pseudosarcomas, these enormous, often pendulous tumors composed of fibrotic, inflammatory and edematous fibroadipose tissue, commonly affect the medial thighs, popliteal area, inguinal and abdominal regions (figure 5). Patients tend to seek treatment when the masses interfere with daily life or when excoriation or skin breakdown occurs.14 Similar to ENV , MLL tends to be a unique lymphedema subtype of the morbidly obese patient.

Figure 6: Due to the marked fibrotic papillomatous changes within the toes, it would not be possible to pinch the dorsal skin of the digit fulfilling the definition of a positive Stemmer sign.

Figure 7: Squared and “sausage” appearing toes of a patient with lymphedema. Dorsally located exaggerated skin creases exist as well.

Diagnosis and Clinical Manifestations

The diagnosis of lymphedema and the aforementioned subtypes can be made in the majority of patients through an adequate history and physical. Classic clinical manifestations specific to lymphedema are well-documented in medical literature15,16,17,18 including:

- Positive Stemmer’s sign – inability to tent or pinch the skin on the dorsum of the digit (figure 6)

- Swollen and squared off toes (“sausage toes”) (figure 7)

- “Orange peel” skin changes (also called peau d’orange) (figure 8)

- Swelling of dorsum of foot (“buffalo hump’)

- Hyperkeratosis

- Papillomatosis; verrucous appearing papules and nodules, sometimes with a “cobblestoned” appearance (figure 9)

- Lymph vesicles

- Lymphorrhea (lymph fluid leakage)

- C utaneous and subcutaneous fibrosis

- Swelling - may be pitting in early stages; non-pitting in middle to late stages

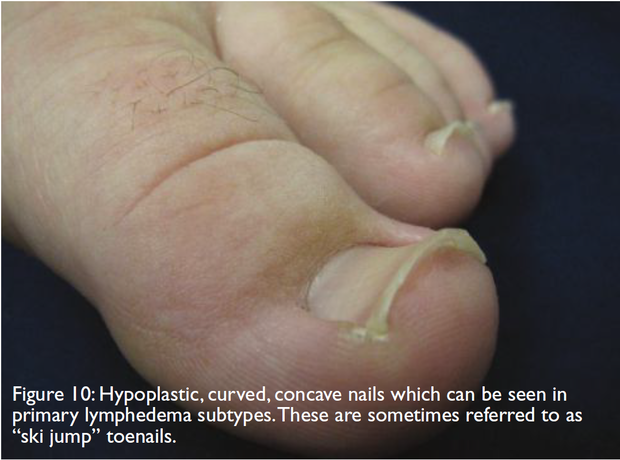

- Hypoplastic and concave toenails - seen in

- subtypes of primary lymphedema (figure 10)

- Ulcerations - late stage lymphedema

Figure 8: The distinctive peau d’ orange or orange peel appearance along a lateral thigh pseudotumor.

Figure 9: Extensive confluent papules and nodules overlie the right medial thigh exhibiting the “cobblestoned” appearance sometimes seen in elephantiasis.

When the diagnosis remains in question, lymphoscintigraphy is the most commonly used imaging modality. Computed axial tomography and magnetic resonance imaging can also be used to visualize the structural changes seen in lymphedema.

Cellulitis: Complication or Predictor?

Cellulitis is a well-recognized complication of lymphedema, with approximately one-third of patients suffering episodes, sometimes recurrently.19 Microbial growth is promoted by the excess protein-rich fluid in the interstitium and impaired immune response characteristic of lymphatic impairment. Recurrent cellulitis leads to progressive damage to lymphatic capillaries, exacerbating pathological skin changes and edema.

Many patients without clinically manifested lymphedema who present with cellulitis may have pre-existing subclinical or “occult” primary lymphedema that predisposes them to developing soft tissue infection. In a study of 40 patients with a first time episode of unilateral lower extremity erysipelas

and no pre-existing lymphedema, 80% of the patients had an abnormal lymphoscintigraphic scan in the affected limb. Surprisingly, lymphoscintigraphic abnormalities were detected in the unaffected limb, as well.20 Another study of 15 patients who presented with an index episode of unilateral cellulitis but no lymphedema diagnosis documented similar findings: an abnormal lymphoscintigraphy was identified within the affected leg in 87% of the patients, yet in 62% of the patients, the scan was abnormal bilaterally.21 Consequently, cellulitis may be a predictor of an occult primary lymphedema, as well as a complication of known lymphedema.

Differential Diagnosis

A number of conditions can be responsible for chronic edema of the leg including congestive heart failure, renal or hepatic malfunction, acute DVT , medication side effects and thyroid disease, to name a few. Chronic venous insufficiency may present with hemosiderin staining, dependent venous swelling, varicosities and ulcerations and, thus, be confused with lymphedema. Unlike lymphedema, uncomplicated CVI tends to be foot sparing with skin changes most notable in the gaiter area. Certainly, advanced CVI can result in coexistent lymphedema (phlebolymphedema) with associated foot/toe swelling, as previously discussed.

Lipedema, also known as the “painful fat syndrome,” is a condition in which there is an abnormal accumulation of fatty tissue resulting in symmetrical swelling of both legs. Seen almost exclusively in women, lipedema generally affects the area between the waist and malleoli, with sparing of the feet. Often these patients have fairly normal dimensions from the waist up where their torso and lower extremities appear “mismatched.” (figure 11) Patients tend to present with a history of lower extremity swelling onset in puberty that progresses and persists despite elevation, compression or profound weight loss. This lack of response to elevation and compression indicates the enlargement is due to deposition of fatty tissue (lipohypertrophy) more than to excess fluid deposition. Patients often report associated pain, significant sensitivity to cutaneous pressure, and easy bruising. Lipedema is not uncommonly misdiagnosed as lymphedema, despite the fact the foot is usually spared and the swelling is symmetric and soft. However, longstanding lipedema in an obese patient can eventually result in secondary lymphedema or lipo-lymphedema which can be identified by associated acral swelling that may include a positive Stemmer’s sign (figure 12).

Figure 12: A 57 year old woman with stereotypical lipedema since her mid 20s presented with a six-year history of new onset dorsal foot swelling suggestive of evolution to lipo-lymphedema.

Treatment

Lymphedema is a chronic, often progressive condition that requires management throughout the patient’s lifetime. First and foremost, weight loss is critical when lymphedema complicates obesity. It is unlikely that a dramatic reduction in leg swelling will occur until affected patients lose considerable weight. Bariatric surgery may be required. If signs of chronic venous insufficiency are present, the patient should be assessed for potentially remedial superficial venous axial reflux.

Compression is the cornerstone of lymphedema treatment. Upon initial diagnosis, treatment by a trained therapist using a multifaceted approach called Complete Decongestive Therapy (CDT ) is useful to reduce edema volume. During CDT , the therapist educates the patient on good skin care and appropriate exercise, performs manual lymphatic drainage therapy (MLD) and applies a complex wrapping of short stretch bandages. Pneumatic compression devices may be used during therapy sessions to augment the compression and MLD components. Once initial volume reduction is achieved, the patient is then fitted for an appropriate compression garment. The end goal of CDT is to prepare the patient to manage the lymphedema at home via “self care.”

Manual lymphatic drainage is an empirically devised therapy intended to move lymph fluid from dysfunctional to healthy regions. Its gentle, specialized massage technique enhances filling of initial cutaneous lymphatics, increases lymphatic contractility and facilitates regeneration of superficial lymphatic vessels. Focused MLD methods can break down fibrotic tissue. MLD sessions must be followed immediately by application of compression bandaging or garments.

Compression bandaging and garments are well established as the foundation of lymphedema treatment. Upon discharge from CDT , patients are encouraged to wear compression garments for up to 20 hours per day to help maintain the reductions achieved in therapy. Generally, it is recommended that compression be applied at a minimum of 30 mm Hg, though stockings and garments that apply higher pressure are available and may be more effective in controlling edema. The main obstacle to daily compression is the difficulty that patients have in donning and doffing the garments, with increasing inconvenience when using a high pressure stocking over a massively swollen disfigured limb. Assistive devices aid stocking application yet are not helpful with removal. Many garments lose their elasticity after 3-6 months and must be replaced.

Long-term self-care presents many challenges for lymphedema patients. When discharged from CDT , patients are encouraged to perform self-manual lymphatic drainage and to apply compression wrapping or garments daily. While highly effective in the clinical setting, there are significant limitations to effectively performing CDT components in the home setting. Self-application of manual lymph drainage is often simply not possible for many patients, especially those who are obese, elderly or dealing with other significant comorbidities. Effective MLD is physically demanding and it should be noted that therapists undergo lengthy training to master the technique. The expectation that a patient will be able to master that technique and provide effective self-MLD for a lifetime is not reasonable for many patients. Application of compression bandaging or garments is not an option for patients who cannot reach to put on their own shoes. Caregiver application of MLD and compression is similarly difficult; caregivers are elderly, unavailable, or simply cannot provide effective treatment.

Pneumatic compression devices (lymphedema pumps) provide a good option for patients who cannot manage their lymphedema through more conservative home treatments. While the evidence base for pumps is not particularly robust, these devices have been used successfully as a home therapy for upper and lower extremity lymphedema for many years. More recent research demonstrated that an advanced pneumatic compression pump actually stimulates the lymphatic system.22 Further, a 12-week study comparing an advanced programmable pump to a traditional nonprogrammable device showed that the group using the advanced device had a 29% reduction in edema compared to a 16% increase in the group using the standard nonprogrammable device.23

Advanced programmable pumps provide a number of treatment options to meet various patient needs, including tolerable yet effective wave-like pressure profiles, bariatric sizing, ability to treat swelling in the abdomen, chest and torso, as well as in the limb, and specialized programs to retreat problem areas. Pumps are fairly easy to don and doff, offering the patient a practical, easily tolerated daily treatment solution, leading to enhanced compliance.23

Conclusion

Based on the aforementioned information, the patient represented in figure 1 was diagnosed with combined chronic venous insufficiency and secondary lymphedema. Signs of advanced lymphovenous hypertension were clinically evident including stasis mediated subcutaneous atrophy within the calves combined with overlying lymphostatic verrucosis (early elephantiasis). Like many of these patients, the subject was morbidly obese.

When the vascular clinician encounters a patient with limb swelling, they should remain vigilant for causative lymphedema, either in isolation or in combination with CVI or lipedema. By recognizing the characteristic physical findings, lymphedema can be easily identified. Lymphedema can be mitigated with appropriate compression modalities including gradient stockings, complete decongestive physiotherapy including manual lymphatic drainage, and/ or advanced pneumatic pumps. The critical importance of weight loss cannot be overstated.

References

- Lymphoedema Framework. Best Practices for the Management of Lymphoedema. International Consensus. London:MEP Ltd. 2006.

- Rockson SG. The Unique Biology of Lymphatic Edema. Lymphat Res Biol. 2009;7(2):97-100.

- Rockson SG. Diagnosis and management of lymphatic vascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol.2008;52(10):799-806.

- Bunke N, Brown K, Bergan J. Phlebolymphedema: Usually unrecognized, often poorly treated. Perspectives in Vascular Surgery and Endovascular Therapy 2009;21(2):65-68.

- Pain. EJSO 2004; 30:508-14.

- David N. Finegold, Vivien Schacht, Mark A. Kimak, Elizabeth C. Lawrence, Etelka Foeldi, Jenny M. Karlsson, Catherine J. Baty, and Robert E. Ferrell. HGF and MET Mutations in Primary and Secondary Lymphedema Lymphatic Research and Biology. June 2008, 6(2): 65-68.

- Rockson, op cit. at Piller N. Phlebolymphoedema/chronic venous lymphatic insufficiency: an introduction to strategies for detection, differentiation and treatment. Phlebology 2009;24:51-55.

- Cavezzi A. Diagnosis and Management of Secondary Phlebolymphedema. In: Lee BB, Bergan J, Rockson SG, eds. Lymphedema: A Concise Compendium of Theory and Practice. 1st ed. Springer London, 2011:547-556.

- Mortimer PS. Implications of the lymphatic system in CVI-associated edema. Angiology 2000;51(1)6-7.

- Fife CE, Carter MJ. Lymphedema in the morbidly obese patient: unique challenges in a unique population. Journal of Ostomy and Wound Management 2008 Jan;54(1):44-56.

- Dean SM, Zirwas MJ, Vander Horst A. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: An institutional analysis of 21 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011 Jun;64(6):1104-10

- Greene A et al. Lower-Extremity Lymphedema and Elevated BodyMass Index N Engl J Med. 2012; 366: 2136-2137.

- Fife CE, Carter MJ. Lymphedema in the morbidly obese patient: unique challenges in a unique population. Journal of Ostomy and Wound Management 2008 Jan;54(1):44-56.

- Lee BB, Andrade M, Bergan J, Boccardo F, Campisi C, Damstra R, Flour M, Gloviczki P, Laredo J, Piller N, Michelini S, Mortimer P, Villavicencio JL. Diagnosis and treatment of primary lymphedema. Consensus Document of the International Union of Phlebology (IUP)- 2009. International Angiology 2010;29(5) 454-470.

- Mortimer PS. Implications of the lymphatic system in CVI-associated edema. Angiology 2000;51(1)3-7.

- Rockson SG. Diagnosis and management of lymphatic vascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol.2008;52(10):799-806.

- Cohen SR, Payne DK, Tunkel RS. Lymphedema: Strategies for Management. Cancer 2001 Aug 15:92(4Suppl):980-987.

- Mortimer PS. Implications of the lymphatic system in CVI-associated edema. Angiology 2000;51(1)3-7.

- Damstra RJ, van Steenself MA, Boosma JH. Nelemans P, Veraart JC. Erysipelas as a sign of subclinical primary lymphoedema: a prospective quantitative scintigraphic study of 40 patients with unilateral erysipelas of the leg. Br. J Dermatol 2008;158(6):1210-15.

- Soo - Br. J Dermatol 2008;158(6):1350-53

- Adams KE, Rasmussen JC, Darne C, Tan IC, Aldrich MB, Marshall MV, Fife CE, Maus EA, Smith LA, Guilloid R, Hoy, S, Sevick-Muraca EA. Direct evidence of lymphatic function improvement after advanced pneumatic compression device treatment of lymphedema. Biomedical Optics Express August 2010; Vol 1, No. 1; 114-125.

- Fife CE, Davey S, Maus EA, Guilliod R, Mayrovitz HN. A randomized controlled trial comparing two types of pneumatic compression for breast cancer-related lymphedema treatment in the home. Support Care Cancer 2012 May 2. [Epub ahead of print] PMID: 22549506

- Ridner SH, McMahon E, Dietrich MS, Hoy S. Home based lymphedema treatment in patients with and without cancer-related lymphedema. Oncology Nursing Forum, July 2008;35(4):671-680.