“I assess the power of a will by how much resistance, pain, torture it endures and knows how to turn to its advantage.” -Friedrich Nietzsche

“I assess the power of a will by how much resistance, pain, torture it endures and knows how to turn to its advantage.” -Friedrich Nietzsche

When one considers the “pain and torture” involved in securing coverage and reimbursement for new technologies, it’s easy to assume Nietzsche was thinking about the long and tortuous path that innovative device companies must endure to secure payer acceptance.

Not to mention the victimization and harassment of physicians who wish to incorporate an innovative new device into their practice before codes are assigned, coverage policy is updated, and fair reimbursement is set. Manufacturers and their physician partners endure a great deal indeed.

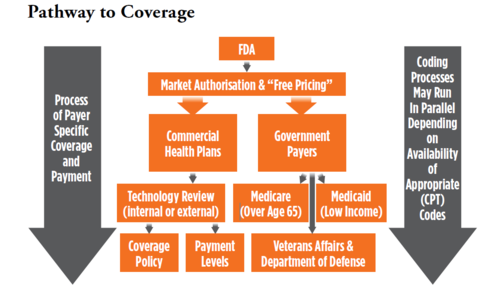

A common misperception is that FDA approval is all that is needed to win reimbursement. Unfortunately, for those who secure hard-won FDA approval, payers can inflict the indignant refusal to cover the device and accompanying procedures by deeming them “Experimental and Investigational.”

The unfortunate truth is that FDA approval is nothing more than a ticket to the dance, so to speak. Authorization is given to market the device, but payers consider safety and efficacy as determined by the FDA approval process as a given. This in no way provides evidence of value for money that drives payer coverage. In the absence of that evidence, payers default to not covered.

A friend, who was once a top decision maker at Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS), told me a story about how a steady procession of hopeful device executives visited his office to show him their new innovation during his tenure. These were well intentioned people who sunk their life savings and/or secured venture funding and were seeking an early read on the pathway to coverage and reimbursement.

He described the pain of having to tell many of them that the data and evidence were not sufficiently aligned with CMS requirements to cover the device. Regrettably, device makers may not discover this sad fact until long after market entry and associated expenses when the assumption that reimbursement is a fait accompli after FDA approval.

“The reporting begins January 1, 2017. Practices that are not participating with Medicare or begin participating with Medicare in 2017 do not have to report. Likewise, practices that treat fewer than 100 Medicare patients during the year do not have to report.”

With a gloom so characteristic of our dark philosopher friend (which can be like the gloom of uncertainty around reimbursement), one might wonder how reimbursement success is achievable. Success is achievable if the pathway and barriers are understood well before submission to FDA, and anticipated headwinds and solutions are incorporated into the reimbursement plan.

First, it is important to understand the elements of market access.

Coding:

The AMA generally requires that a new procedure/device demonstrate:

- Widespread use (nationally)

- A prescriptive number and quality of five publications

- The procedure that incorporates the device is not described by an existing code

Other notes:

- The assignment of a Category 1 CPT code is nothing more than a way for claims to be processed in automated fashion by payers and reimbursed according to an assigned dollar amount (as proposed by Societies and approved and published by CMS).

- A CPT code in no way implied that a device or procedure will be covered or paid. There are many examples of CPT approved procedures which are not covered by payers.

- The miscellaneous vascular CPT 37799 code is often referred to the 37799 black hole because the payer receiving the claim has no way to identify the specific device, casting the claim into a black hole of denials and appeals and non-payment or underpayment. If using the 37799 code the “black hole” effect can be reduced by noting the device name on the claim form as well as in the documentation supporting the claim.

Coverage:

Payers make a decision whether or not to include a new technology in their coverage policies along with specific requirements which must be fulfilled for a claim to be valid.

Other notes:

- Coverage policy decisions are often made based on a score that independent technology assessment firms assign based on their assessment of the strength and quality of the published literature. Many commercial carriers are not staffed to do internal assessments on the many new technologies that come to market. Thus they rely on these services to provide a score. If evidence is weak or low quality the score will be low. A non-covered decision (experimental and investigational) is the most common result.

- Hayes, Inc. is the most prominent tech assessment firm

- Inclusion in coverage policy can be accelerated if Society Guidelines include the technology.

- Society guidelines are not updated frequently.

- Widespread physician demand for the technology can drive positive policy decisions.

- Inclusion in coverage policy is an indication that the payer is concerned about overuse or inappropriate use and, as a result intends to manage claims closely.

Reimbursement

During the interim coding period when CPT 37799 is utilized, it is extremely important to match requirements of specific payer coverage policy to the documentation. Each claim is processed manually and reimbursement is dependent on a clean claim that is defensible when challenged by the payer claim staffer. CPT valuation is set by CMS and applies to Medicare claims. Commercial carriers typically assign a higher value than Medicare rates.

Behind the Scenes Drivers

As noted previously, the most openly stated limiting factor in terms of limited coverage and reimbursement or delayed decision making by payers is the need for peer reviewed published evidence that covering and reimbursing the new technology will result in a better outcome than the standard of care. The evidence bar is often elevated to require such evidence to be comparable to standard of care when it is known that few of these types of studies are done.

This is often because the standard of care is not well defined from an evidence standpoint. The demand for such data and the fact that such expensive and time-consuming studies are not typically part of an FDA approval process is a de facto justification for casting new technologies into the dreaded “Experimental and Investigational” category of non-coverage. There are ways to deal with this common problem which we discuss later.

“Coverage policies are one of the most effective ways to manage spending and limit spending.”

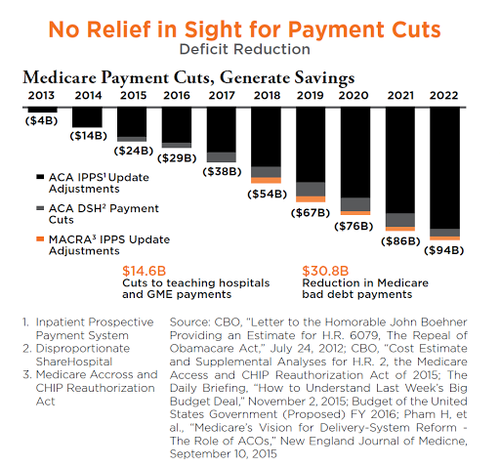

Payers are often publically-traded companies with shareholder expectations on revenue and profit growth. Even the Medicare contractors are commercial companies with internal financial goals who have won a bid from CMS to manage benefits for Medicare recipients. The Medicare Trust Fund, the pool of money that the government allocates for Medicare beneficiaries, is under constant pressure and the Medicare carriers are charged with ensuring that it is spent efficiently.

Coverage policies are one of the most effective ways to manage spending and limit spending. The planned Medicare cuts exacerbate the challenges in dealing with Medicare carriers when seeking coverage and reimbursement.

No Relief in Sight for Payment Cuts

New Pathway to Earlier CMS Coverage

On October 24, 2016, the FDA and CMS announced the full implementation of the Program for Parallel Review of Medical Devices. The program, which is intended to reduce the time between FDA marketing approval and Medicare coverage decisions through CMS’s National Coverage Determination (NCD) process, facilitates earlier access to innovative medical technologies. It allows the agencies to review information about a medical device concurrently with making their premarket review and coverage decisions consistent with their respective statutory authority.

In support of this decision, the program benefits manufacturers by giving them the opportunity to receive and address input from both agencies during pivotal clinical trial design, and that concurrent review can reduce the time from the end of the FDA review process to an NCD. To be considered for the program, manufacturers must submit the following information before beginning the pivotal clinical trial design development phase:

-

Basic information about the product, disease or condition the device and its state (stage) of development

-

Manufacturer’s statements:

-Regarding its intent to meet jointly with both FDA and CMS to gather and incorporate feedback in clinical trial design

- That the device will require an original or supplemental PMA or for FDA to grant a “de novo” request

- That the device addresses the public health needs of the Medicare population

As was the case during the pilot program phase, the agencies will accept a maximum of five devices into the program per year. When deciding whether to accept a device, the agencies will prioritize innovative medical devices and devices expected to have the most impact on the Medicare population.

As to whether to apply for the program, manufacturers should consider the following:

- Whether the device can be covered by a Medicare regional contractor without a NCD, i.e., whether the device can otherwise be reimbursed under existing codes or through local coverage determinations (LCDs)

- Whether an adverse NCD would create obstacles to obtaining an LCD or thirdparty payer coverage and reimbursement

- If there are separate coding and reimbursement considerations that are not addressed by the Parallel Review Program

- If the device will be primarily used in patient populations not covered by Medicare

- Whether the FDA’s decision to decline clearance or approval of an indication could affect Medicare coverage of off-label indications (and to what extent)

- Whether FDA knowledge of the company’s intent to obtain Medicare coverage for an unapproved indication could delay FDA approval as it applies scrutiny to those prospective indications

Coverage with Evidence Development

Coverage with evidence (CED) is a paradigm whereby Medicare covers items and services on the condition that they are furnished in the context of approved clinical studies or with the collection of additional clinical data.

In making coverage decisions involving CED, CMS decides after a formal review of the medical literature to cover an item or service only in the context of an approved clinical study or when additional clinical data are collected to assess the appropriateness of an item or service for use with a particular patient.

Although Medicare generally does not cover experimental or investigational items and services as reasonable and necessary, the Medicare program has adopted coverage policies that relate to clinical studies before the formal release in 2006 of the CED paradigm. In 1995, CMS (then known as the Health Care Financing Administration) established coverage for certain items furnished in FDA-approved IDE trials.

CMS updated the coverage criteria for certain items and services in IDE trials effective January 1, 2015. In response to a June 7, 2000 Executive Memorandum, CMS (then HCFA) issued an NCD for coverage of routine costs in clinical trials, commonly referred to as the Clinical Trial Policy. The Clinical Trial Policy was revised in 2007 through the NCD reconsideration process.

In 2005, CMS began to implement NCDs requiring study participation (for example: NCD Manual §50.3 Cochlear Implantation Moderate Hearing Loss; NCD Manual §220.6.13 FDG PET for Dementia and Neurodegenerative Diseases). Subsequently, CMS issued guidance on the CED paradigm in the 2006 guidance document entitled National Coverage Determinations with Data Collection as a Condition of Coverage: Coverage with Evidence Development.

The 2006 document introduced two arms of CED which included Clinical Study Participation (CSP), and Coverage with Appropriateness Determination (CAD). While the concepts behind both arms are described in this document, CMS no longer uses this terminology to distinguish the two.

While CMS has embraced an evidence-based medicine coverage paradigm, CMS is increasingly challenged to respond to requests for coverage of certain items and services when they find that the expectations of interested parties are disproportionate to the existing evidence base.

At the same time, it is believed that CMS should support evidence development for certain innovative technologies that are likely to show benefit for the Medicare population, but where the available evidence base does not provide a sufficiently persuasive basis for coverage outside the context of a clinical study, which may be the case for new technologies, or for existing technologies for which the evidence is incomplete.

Coverage in the context of ongoing clinical research protocols or with additional data collection can expedite earlier patient access to innovative technology while ensuring that systematic patient safeguards, including assurance that the technology is provided to clinically appropriate patients, are in place to reduce the risks inherent to new technologies, or to new applications of older technologies.

Commercial insurers, especially those who are integrated with medical groups, may also have in-house or partnership programs to assess new technologies on a CED basis. Major national and regional payers such as Aetna, Humana, Kaiser, Wellpoint, BSBS Association, MACs (Palmetto, Novitas and others) and CMS participate in a Center for Technology Policy program called the Green Park Collaborative which describes itself as “working to improve clinical research by cultivating collaboration between drug and device developers, private and public payers, clinicians, researchers, regulators, and the patients that they all serve.

A multi-stakeholder forum, GPC develops condition and technology-specific study design recommendations to guide the creation of evidence needed to inform both clinical and payment decisions.”

“As we have seen, FDA approval does not drive coverage or reimbursement.”

Other Potential Solutions

As we have seen, FDA approval does not drive coverage or reimbursement. It is a proverbial ticket to the dance, but without published health economic and outcomes evidence and physician demand the technology will stand in the corner with no dance partners. RCTs and large comparative studies are not feasible in most cases, especially devices approved under a 510(k).

There are, however, options and solutions which may provide enough proof of value that coverage and reimbursement may be granted, or at least the timeline between FDA approval and reimbursement can be shortened. It is always best to develop strategies for evidence development well before approval and launch. Those strategic initiatives include:

- Development and publication of Comparative Effectiveness and/or Budget Impact Assessment - Technical analyses developed by the health economist

- Retrospective claims analyses from large claims databases such as Truven, Premier or CMS Society registries may also be a good source

- Collaboration with select commercial payers to conduct studies which provide value or outcomes data that can support coverage decisions

There is no easy path to secure coverage and reimbursement and success can take years. When new technologies are brought to market without a prior understanding of the barriers to coverage and reimbursement, physicians are hobbled and patients are denied the opportunity to benefit from innovation. It is important to persevere, find alternative pathways and partnerships and suffer through.

“When new technologies are brought to market without a prior understanding of the barriers to coverage and reimbursement, physicians are hobbled and patients are denied the opportunity to benefit from innovation.”