I recently visited a primary care office that strongly supports our practice to share a couple of interesting cases and a recent acute thrombosis that was sent to our office one month after initial diagnosis. I spent the first 15 minutes with staff members reviewing some compression garments we fit for their patients, a case of Blue Rubber Nevis Syndrome, and superficial phlebitis.

I recently visited a primary care office that strongly supports our practice to share a couple of interesting cases and a recent acute thrombosis that was sent to our office one month after initial diagnosis. I spent the first 15 minutes with staff members reviewing some compression garments we fit for their patients, a case of Blue Rubber Nevis Syndrome, and superficial phlebitis.

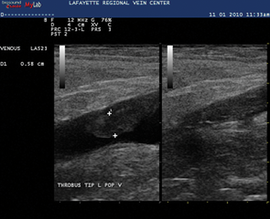

Once the physicians were free, we discussed an extensive, unprovoked iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis (DVT) case, and addressed questions of current prophylaxis guidelines for total joint replacement, venous leg ulcer care, differentiating edema from venous hypertension vs. lymphedema and, ultimately, the congestive heart failure patient with swollen legs.

I personally cherish the opportunities to sit with other physicians and never arrive with a set agenda. I knew the DVT case I had recently evaluated offered a teaching opportunity, yet the questions we addressed went far beyond a C2 patient. Primary care providers and other specialist physicians are hungry for knowledge that helps manage patients more effectively, refer appropriately, and recognize when urgent evaluations are indicated.

This office visit, and the questions posed by the physicans, offered me the opportunity to arm them with a venous thromboembolic event (VTE) risk assessment tool, acute management of VTE skills, and long-term prevention strategies, e.g., the three phases of DVT.

The following offers insight into the three phases of DVT and opportunities to elevate the standard of care in your community, while growing the thrombotic event portion of your practice.

Preventing acute DVT/prophylaxis strategies

Prevention strategies have recently emerged and have been accompanied by governmental pressures to minimize occurrence with hospitalization. We see so many people whose lives are turned upside down after an acute lower extremity DVT.

We evaluate many patients who want to know their risk or be advised for risk reduction before total knee/hip surgery. There are many ways, in theory, to help minimize thrombotic events simply by avoiding features of Virchow’s triad. Simple recommendations for healthy vein habits are as follows:

- Walking is better than sitting/standing

- Wear compression stockings when in it makes sense:

-Occupations involving prolonged sitting or standing

-Prolonged car/plane rides - Target walking 10,000 steps/day – this is a standard philosophy. This is not always easy, but many patients get no activity, and starting a walking habit offers many opportunities.

- Maintain a normal weight, if possible. If a patient’s body mass index is over 40, the risk of developing a blood clot is three times the normal weight person all other things being equal.

These are merely generic steps that all persons should strive for to help reduce their risk of acute thrombotic events, yet none of them should be minimized for their benefits.

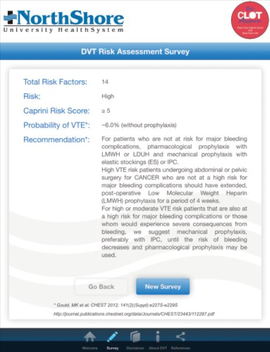

Keep in mind, however, that the risk of developing blood clots is an INDIVIDUAL risk. We cannot look at someone and see his/her risk. The Caprini DVT Score has proven quite useful in our practice when patients want to know their baseline risk.

We employ this tool for all patients preparing for total knee or hip replacement surgery and assist in prophylaxis recommendations. The Caprini DVT Score is a free and user-friendly app at the Apple App Store. When patients are engaged, they consciously own his/her risk for developing a DVT, and many will help to educate loved ones who may also be at risk.

“The Caprini DVT Score is a free and user-friendly app at the Apple App Store. When patients are engaged, they consciously own their risks for developing DVTs, and many will help to educate loved ones who may also be at risk.”

Prophylaxis measures may be tailored to individualized risk. The meeting I shared in the opening paragraph allowed the PCPs to review the Caprini Score on an iPad and apply their typical patient seeking surgical correction. They were able to identify that in the majority of instances (e.g., major abdominal, total joint replacement, etc.), their patients are considered high risk.

They additionally recognized the importance of personal and family history of thrombotic events. A discussion of prophylaxis standards ensued and based upon the literature, the following may be assumed for total joint replacement: ASA reduces VTE incidence over placebo by 25%, LMWH reduces the VTE incidence by 33% vs. placebo, and rivaroxaban reduces the VTE incidence by 66%.

Prophylaxis options also include early ambulation, sequential compression devices, and compression therapy. The key, if offering prophylaxis counseling, is recognizing that not all surgeries need pharmacologic intervention, and that not only orthopedic patients are at risk.

Patients should be educated about their risk, and there should be considerations with appropriate supportive documentation to the PCP and specialist. Individualized risk assessment has a role in every vein practice. Patients must own their risk and recognize how they can minimize this threat.

This documentation helps to change practice, with the ultimate goal of minimizing potentially preventable thrombotic events. We cannot prevent all events, yet when a patient is engaged and shares this concern, there is always an opportunity to help narrow the education gap.

“The three principles of blood clot management have been proven in randomized trials to arrest the clotting process and help to limit complications. These involve walking, compression, and either anti-inflammatories/blood thinners.”

Acute management principles

The three principles of blood clot management have been proven in randomized trials to arrest the clotting process and help to limit complications. These involve walking, compression, and either anti-inflammatories/blood thinners.

-

Walking & Compression Therapy – Randomized clinical trials have proven that patients subjected to compression and walking do better than when placed at bedrest and elevation. The benefits include less pain, swelling, and complications when compared to the bedrest population. Walking enhances blood flow, while bedrest offers a recipe for thrombus extension. When we think about what leads to blood clots, three factors are known: injury to a vessel; stasis/stagnant flow (immobilized limb); and blood chemistry, such as a clotting disorder that shifts the curve toward clotting.

The combination of walking and compression is widely accepted, and many believe it speeds recovery. We’ll learn more about the role of compression when it comes to reducing the risk of long-term complications. In patients with extensive edema, we often employ Unna boots for two days and transition subjects to compression appropriate for their symptoms and extent of thrombus. -

Anticoagulation – This depends largely upon two things: the burden of clot and the risk of bleeding. The chart below combines the current guidelines as reported by the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP). The ACCP studies the world literature regarding deep and superficial thrombosis and updates their guidelines every four years. We expect to see new guidelines in 2016.

The choice of approach is guided by the burden of disease. When options exist, providers must weigh what is in the best interest of the patient. The importance of this phase is simply to halt the clotting process and prevent complications of the acute event. The outcomes, however, are tied to the intensity and duration of anticoagulation. The guide below highlights our current practice that largely mirrors the Chest guidelines.

"Acute DVT management is rarely easy. A patient-centered approach involving a multidisciplinary team will allow a comprehensive way to address any thrombotic pattern."

When you are managing the acute thrombotic process, patients have questions and it is imperative to have educational material. Patients and family members want to know why a clot developed, and it takes time to address the concerns. In many instances, we will bring patients back within one week to reassess symptoms and discuss future testing when unprovoked.

We also coordinate care with a hematologist/oncologist for a team approach. Although thrombophilia testing remains controversial, acute testing for Factor V Leiden, prothrombin gene mutation, and homocysteine levels offer a reliable opportunity to address concerns patients have at a fraction of the cost of formal testing, which is not indicated acutely.

Acute deep vein thrombosis management is often complex, and yet an organized approach helps reduce patient anxiety and build confidence in the team providing coordinated care. The following objectives will help a provider meet current standards of a vein practice:

- Personal access to perform or colleague who can be reached urgently for iliocaval/iliofemoral events in need and eligible for mechanicopharmacologic thrombolysis

- Anticoagulation supplies in the office

-LMWH vs. Xa inhibitor/direct thrombin inhibitor samples

-Allows treatment to begin in the office

-Many pharmaceutical companies offer samples for this indication. Many of the same companies offer prescription assistance when cost may prove to be an issue. - Educational material about DVT and principles of care that parallel what patients are learning in the office. Many EMR templates share archaic recommendations for patients. Make sure you have current material readily available with your contact numbers should symptoms or the condition worsen.

- Compression supplies

-Compression has so many roles in vein care, yet its role in acute DVT management cannot be overlooked, as symptoms are so readily reduced. The reduction in incidence of post-thrombotic syndrome make it an important service for a vein practice to offer.

-We will often provide Unna boot therapy for 3-4 days for acute decompression, and then transition to compression garments at follow up. The reduction of symptoms is often dramatic and allows a patient to appreciate near-term relief for a complex problem.

Acute DVT management is rarely easy. A patient-centered approach involving a multidisciplinary team will allow a comprehensive way to address any thrombotic pattern. Recognize that patients need counseling on how this event has potentially changed his/her life. Additional follow up may occur within a week to address new questions or concerns.

This is merely the first visit for a complex problem that may include testing for malignancy. Educational handouts are important to share, in addition to warning signs, should symptoms worsen.

Recurrent DVT & post-thrombotic syndrome prevention

Of all things to consider after the acute event has been managed, it is the prevention of a new event that could bring the same risk. Long-term management involves the safe transition from full anticoagulation to aspirin and acquiring healthy vein habits to help reduce the incidence of post-thrombotic syndrome.

Of all things to consider after the acute event has been managed, it is the prevention of a new event that could bring the same risk. Long-term management involves the safe transition from full anticoagulation to aspirin and acquiring healthy vein habits to help reduce the incidence of post-thrombotic syndrome.

Generally speaking, the amount of additional testing for someone with a DVT varies on whether it was provoked vs. unprovoked. A patient with a provoked blood clot (e.g., something triggered the event like total replacement knee surgery, a long car ride, etc.) does better than when compared to the patient with an unprovoked event. Unprovoked events must truly consider potential underlying pathology. The 67-year-old patient with an unprovoked acute femoral vein thrombosis has a far different workup vs. the provoked event.

Provoked events simply fare better in near-term mortality and in long-term limb health. If we know there is a defined trigger, (surgery, long plane ride) very little workup or additional testing is often needed. The important part becomes stopping anticoagulation after the appropriate duration in a controlled manner. More on this in the next segment.

Unprovoked events fare more poorly and are commonly associated with an underlying condition, including underlying blood-borne thrombophilia and/ or cancer. Depending upon age, comorbidity, family history, and additional detailed questioning, a plan will ultimately need to be developed to help determine what incited the potentially limb-threatening event.

Thrombophilia testing for acquired and inherited thrombophilias are commonly performed. Acute testing, with rare exceptions, is simply unreliable, as many of the agents tested will be artificially low. This is difficult to understand for many patients, yet common things are common.

The three most common disorders that may be tested at any time are: homocysteine level, prothrombin gene mutation, and Factor V Leiden. We generally do not advocate for immediate assessment of blood disorders. We prefer an organized approach, timed with plans to remove patients from blood thinner, or soon thereafter.

“Post-thrombotic syndrome is a common condition that occurs after a significant thrombosis of the lower extremity. The bigger the clot burden and more proximal the obstruction, the higher the incidence of this debilitating condition.”

Preventing recurrent DVT is a multifactorial process. The duration of anticoagulation is generally established by current guidelines. If the reason for developing a clot is ever present (e.g., malignancy), oral anticoagulation is often continued until the process is resolved. The risk of recurrent DVT has been shown to be dependent upon the intensity and duration of anticoagulation.

At the time we wish to discontinue Coumadin or one of the Xa inhibitors, we will order a D-dimer test to assess for any ongoing thrombotic activity. If this test is negative, we transition to aspirin therapy, recommending 162 mg (two baby aspirin) per day. If the test is positive, we will continue anticoagulation for another 6-12 weeks, then repeat the D-dimer at that time.

Studies have shown that patients with an elevated Factor VIII activity or a positive D-dimer that turns (after previously being normal) at one month are at greater risk of developing another event. If the Factor VIII and D-dimer are negative, transition to aspirin is recommended and is proven to help reduce recurrence.

Post-thrombotic syndrome is a common condition that occurs after a significant thrombosis of the lower extremity. The bigger the clot burden and more proximal the obstruction, the higher the incidence of this debilitating condition. Characterized by painful, swollen, discolored, and often ulcerated limb, the incidence may be reduced by 50% by simply wearing calf-high 30-40 mmHg compression garment.

Conclusion

In summary, the specialist in venous and lymphatic pathology has the ability to make a big impact for patients presenting with acute thrombotic pathology. Patients and communities need a reliable place to send patients with this complex condition. In order to effectively manage these patients, it is important to be skilled in all three phases of VTE management. Grassroots marketing is never easy, yet when you are ultimately helping providers more effectively address their patient concerns, you are making a difference in the community and, in theory, saving lives.

There are subscribers of Vein Magazine who merely address C1 & C2 patients. I would suggest there are far greater opportunities for us to take a role in all venous and lymphatic care in elevating quality, while narrowing an education gap. Whether a one-on-one encounter over lunch or a physician newsletter, there is a hunger in understanding when to send someone for catheter-directed mechanicopharmacolysis, what compression options are most suitable for a given condition, and even how to workup the acute DVT patient.

Take the time to shape how your practice will participate.