Studies show mental illnesses are tied to vascular disease. Here is what you need to know.

ACCORDING TO DATA from the 2018 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), chronic disease affects one in two people.1 Mental health disorders and chronic disease, such as vascular disease, predispose people to develop significantly more mental health disorders and more chronic disease.2, 3 Good mental health is “a dynamic state of internal equilibrium which enables individuals to use their abilities in harmony with universal values of society.” 4 A mental health disorder is therefore “a syndrome characterized by clinically significant disturbance in an individual’s cognition, emotion regulation, or behavior that reflects a dysfunction in the psychological, biological, or developmental processes underlying mental functioning.”5 Women’s mental health issues are most often mood and/or anxiety disorders while men have higher rates of antisocial and substance use disorders.6 Mental health disorders are under-identified by healthcare professionals and by people themselves.

Even if they know they have a mental illness such as depression, the stigma surrounding mental illness, especially for people of color, makes them reluctant to seek help.7 Persistently depressed people are less likely to adhere to behaviors that reduce the risk of recurrent chronic disease such as quitting smoking, taking medications, or exercising.8

Physical disease can lead to mental health disorders

Although they have not reached the level of awareness of chronic diseases such as diabetes, heart failure or hypertension, healthcare providers should be aware of mental health problems experienced by people with other long-standing cardiovascular diseases including chronic venous disease, lymphedema, or lipedema (a form of lymphedema).9 These diseases are dominated by women. While it might not be obvious that a bulging vein on a leg can worsen a person’s mental health, in fact, for women only, the entire range of venous diseases of the leg, including conditions with symptoms or telangiectasias only, or with varicose veins (VV) with and without concomitant disease, are associated with compromised mental quality of life.10

Conditions associated with chronic venous disease (CVD), including, venous insufficiency, lymphedema (swelling), and chronic wounds or ulcers, can force people into isolation with very poor social engagement.11 For example, while pain was the most profound experience had by people living with chronic leg ulceration, their anxiety and depression, both mental health disorders, were significantly associated with odor and exudate from their wounds.12 The risk of additional trauma and the stigmatizing effect of an offensive wound were also reasons people withdrew from social activities.

High affective reactivity can lead to health issues

Physical disease can result in anxiety and depression, but the reverse can also be true. Good mental health is a state of well-being that allows people to cope with normal stresses of life and function productively.13 Stressors can be predictable or unexpected, and no matter which, some people take them in stride despite huge physical challenges, while others have heightened affective reactivity to any stressor.14 Affective reactivity is the magnitude of a person’s change in affect (outward expression of internal emotions) on days of stressors, compared to stressor-free days.

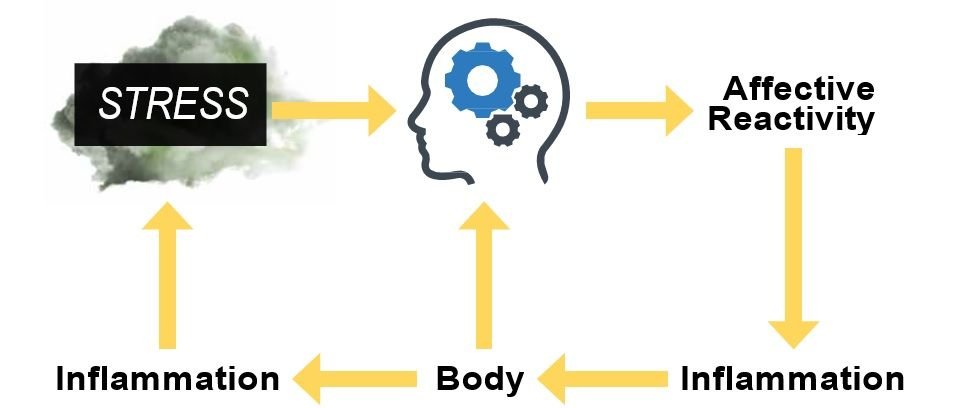

In a study of 4,242 individuals in the Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS) survey, people with higher affective reactivity increased their long-term risk of developing a chronic physical health condition.14 The link between affective reactivity and development of disease may be inflammation. Adults who fail to maintain a positive affect when faced with minor stressors in every- day life had significantly elevated levels of IL-6, a marker of inflammation (see Figure 1). Women who experience increased negative affect when faced with minor stressors may be at particular risk for inflammation.15 A fast way to assess affective reactivity risk in your clinic patients is a six-item questionnaire, copyrighted, but free for use at this link: https://github.com/transatlantic-comppsych/ Affective-Reactivity-Index (Table 1).16

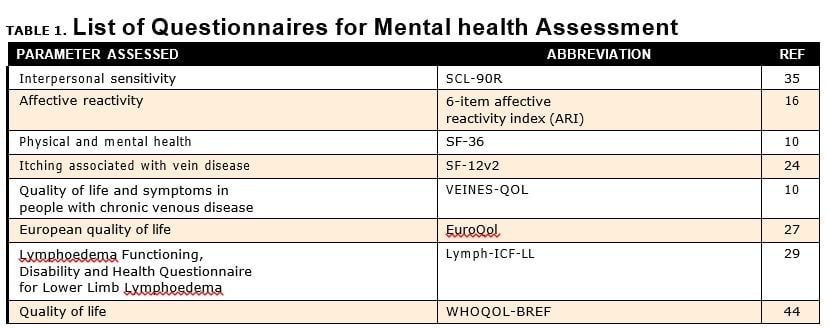

SF-12v2 = 12 questions selected from the short form 36 health questionnaire (SF36);

SCL-90R=Symptom Checklist-90-Revised instrument;

WHOQOL-BREF = abbreviated generic Quality of Life Scale developed through the World Health Organization

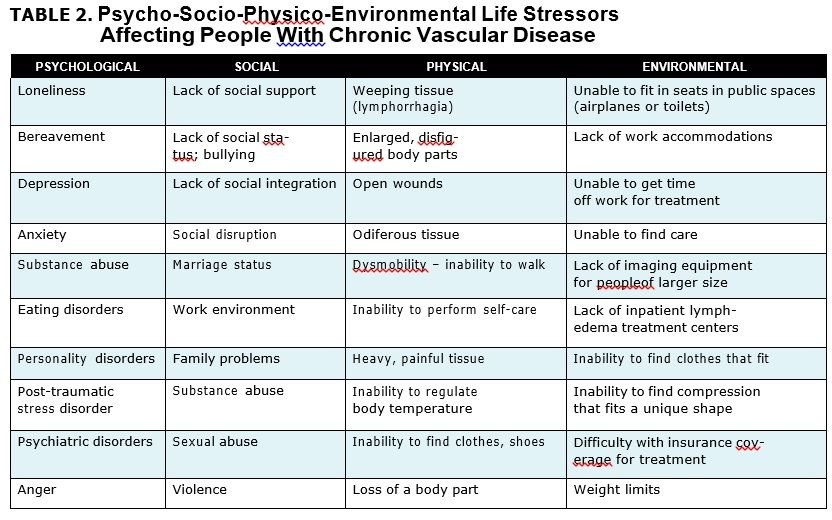

In addition to withdrawing socially, people living with vascular disease can find it difficult to care for their disease due to psychosocial stressors from psychological factors and the surrounding social environment.17 Psycho-social stress results when we look at a perceived threat in our lives (real or imagined) and discern that it may require resources we don’t have.18 Physical (vascular) disease is, therefore, a stressor, so while mental illness can be attributed to biogenetic causes, it is worsened by affective reactivity and psycho-socio-physical factors (Table 2).

When people are first diagnosed with a disease, they may experience acute stress disorder, a mental health diagnosis within trauma and stressor-related disorders in the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition (DSM-V). People with high grief symptoms when presented with acute stress developed ~20% higher IL-6 levels than people with lower initial grief levels, confirming again the association between stress and inflammation.19

There may be better grief models, but the five stages model of death and dying by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross when applied to the living situation of people with vascular disease, can illustrate how people feel when they present to you at your office (Table 3).20, 21 Thinking about another person’s stress is a form of empathy, the opposite of narcissism.22

Three vascular diseases

CVD and lipedema are chronic vascular diseases that can cause lymphedema. The development of lymphedema can lead to co-morbidities that cause significant illness including obesity, chronic ulcers, and cellulitis and all three can lead to the need for unrelenting care to treat current issues and prevent progression. Care for these diseases includes daily compression garments of many types, sometimes nighttime garments, the need to see certified lymphedema therapists for manual lymphatic drainage therapy and other manual therapies, and the use of an intermittent pneumatic compression pump for an hour once and sometimes twice a day, mobility assist devices, frequent health care visits and often the need for caregiver assistance. These diseases are known to be associated with mental health disorders.

Chronic venous disease

Chronic venous disease is a broad spectrum of changes in the structure and function of the venous system in which blood return is seriously compromised, of- ten due to elevated venous pressure, resulting in clinical manifestations and other serious concerns affecting millions of people.23

Investigators in a 2001 study on 1,054 patients with and 259 people without VV, administered the questionnaire, VEINES-QOL, a disease-specific measure of chronic venous disorders of the leg that produces two summary scores: the VEINES-QOL, an overall estimate of quality of life (QOL), and the VEINES-SYM, an overall estimate of symptom frequency of CVD of the leg. Physical and mental scores for men and women with VV were lower (worse) than population norms. The largest difference between mean VEINES-QOL scores was for those with healed or active ulcers with VV versus those without, meaning VV reduced QOL even further. The largest differences in mean VEINES- SYM scores were found in patients with edema or an ulcer with VV compared to patients without VV.24 When a person has VV and edema or an ulcer or history of an ulcer, especially if they have VV, a mental health assessment should be considered followed by supportive care which can include a referral to a mental health specialist.

Is venous itching associated with mental health issues?

Something considered clinically minor, such as itching, can signal a problem in mental health. In a study of 700 individuals with VV and itch compared to those with VV without itch, based on the SF-12v2, consisting of 12 questions selected from the short form 36 health questionnaire (SF-36), persons with leg or feet itch had significantly poorer physical quality of life, more comorbid conditions, and higher leg pain, and were more than one standard deviation below the mean for the United States for their mental and physical health scores.24 Asking about itching and taking notice of a positive answer is a simple addition to any clinic intake questionnaire.

A negative and a positive for mental health in CVD

Not all studies support mental health issues in people with CVD. In a 2003 study using the physical and mental component scores of the SF-36, investigators found in 2,404 men and women, that venous disease affects function (what a person can do) but does not seem to affect well-being (how a person feels).26

However, surgical intervention can improve mental health in people with CVD suggesting the presence of mental health issues that can be improved upon in this population. After eighty-five patients underwent surgery on the saphenous system, nine had short saphenous vein surgery, and fifteen had both long and short saphenous vein surgery, SF-36 scores improved at 6 weeks post-surgery in all domains of health but only mental health reached significance for improvement.27 Similarly, after vein ablation for 83 patients with chronic venous insufficiency, quality of life by the EuroQol descriptive system (EQ-5D) questionnaire was significantly better in all domains: pain/discomfort (58%), mobility (42%), anxiety/depression (38%), usual activities (19%), and self-care (9%).28

Lymphedema

Lymphedema is a chronic disease whose care requires multiple resources. There is no curative treatment, though surgical options are promising. Primary lymphedema is characterized by intrauterine malformation or genetic deformity with impaired lymphatic transport. Secondary lymphedema is caused by an ineffective lymphatic flow, most frequently the result of traumatic or iatrogenic lymphatic vessel interruption or overload from obesity or chronic venous insufficiency. Because of reduced lymphatic transport, interstitial fluid bound and unbound to glycosaminoglycans accumulates resulting in chronic swelling, inflammation, fibrosis, and lymphedema.29

Mental health and lymphedema

There are multiple studies demonstrating compromised mental health for people living with lymphedema. For example, twenty-five patients with unilateral lymphedema of the lower limb completed the Lymphoedema Functioning, Disability and Health Questionnaire for Lower Limb Lymphoedema (Lymph-ICF-LL) domain scores. Mobility and mental function were the most compromised domains and both correlated with corresponding domains in the SF-36.30

In a meta-analysis of 23 studies, with twelve articles utilizing qualitative methodology and 11 quantitative methodologies, the quantitative studies showed statistically significant poorer social well-being in persons with lymphedema, including perceptions related to body image, appearance, sexuality, and social barriers. No statistically significant differences were found between persons with and without lymphedema in the domains of emotional well-being (happy or sad) and psychological distress (depression and anxiety). All 12 of the qualitative studies consistently described negative psychological impact (negative self-identity, emotional disturbance, psychological distress) and negative social impact (marginalization, financial burden, perceived diminished sexuality, social isolation, perceived social abandonment, public insensitivity, non-supportive work environment).31 The authors of this study found that people are absolutely negatively affected by lymphedema.

In an analysis of 15,926 health survey interviews and 1,597,258 electronic health records (EHRs), with 52% women, average age 47 years, anemia, depression or anxiety, migraine or frequent headaches, osteoporosis, thyroidal dis- eases and varicose veins were more than twice as prevalent in women, yet varicose veins were not as often identified in EHRs compared to handwritten health records.32 There is a question on whether these diseases are judged by healthcare providers to be clinically relevant enough to be added to the EHR.33 An appeal of this paper is to please document varicose veins in EHRs even if the patient has no complaints; they could be a sign of more significant disease.34

Treatment of lymphedema

Treatment of mental health can improve lymphedema. In a study of women with breast-cancer-associated lymphedema, 15 received complete decongestive therapy (CDT) and 16 received CDT plus a relaxation technique described as 15 minutes of contraction of different muscle groups for 5±7 seconds then relaxation for 10 seconds which was continued by the women at home. There was a significant reduction in depression and anxiety scores in the group that underwent the relaxation technique compared to the group that did not. 35 The reverse is also, true. Physical treatment of people with unilateral lower limb lymphedema by complex decongestive therapy over 20 sessions significantly decreased limb volume, mobility, the SF-36 Physical Component Summary score, the Social Appearance Anxiety Scale score, and the Beck Depression Inventory score.36

Lipedema

Lipedema is the abnormal deposition of subcutaneous fat (loose connective tissue), leading to disproportionate and symmetric enlargement of the lower body, and, in 80%, the arms. This vascular disease overwhelmingly affects women and is probably due to a genetic predisposition and the location of tissue linked to sex hormone changes. Hypersensitivity of the tissue is present in most where severe daily pain is common and can distinguish women with lipedema from people with lymphedema.37 Hematoma formation is also common (easy bruising). While lipedema is not the same as obesity, obesity may be present, especially in later stages, and obesity increases the risk of depression.38-40 Some women with lipedema have obesity, lymphedema, and CVD, sometimes called lipophlebolymphedema.

Figure 1. Cycle of stress affecting brain function which due to affective reactivity causes inflammation in the body which in turn creates stress that affects the brain.

Quality of life and mental health in lipedema

Mental health is prevalent in women with lipedema. Rates of self-reported depression range from 17-30% and self-reported anxiety from 18-30%.41-43 In a single clinic, women with lipedema had more self-reported depression than patients with paralysis.44 In a lipedema surgical clinic, of 100 women with lipedema, one out of eight had attempted suicide at least once.45

Quality of life measured by the WHO-QOL-BREF, an abbreviated generic Quality of Life Scale developed through the World Health Organization (WHO), was lower in all domains for women with lipedema than the general population.46 Lower quality of life in women with lipedema was predicted by higher symptom severity, lower mobility, higher appearance-related distress, and higher depression severity. Appear- ance-related distress and depression are important when trying to understand the experience of women with lipedema.47

Interpersonal sensitivity and lipedema

Interpersonal sensitivity is the undue and excessive awareness of, and sensitivity to, the behavior and feelings of others. Individuals with this trait are sensitive to perceived or actual criticism or rejection. Interpersonal sensitivity has been proposed as one of the vulnerability factors leading to depression and also as an underlying personality trait in anxiety disorders.48,49 The interpersonal sensitivity scale of the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised instrument (SCL-90R) differentiated between women with lipedema and people with lymphedema, where women with lipedema scored lower (more symptoms).50 High interpersonal sensitivity changes the physical body by shortening telomeres; this can also happen with cellular aging, mood disorders, and a multitude of other physical diseases.51 Inflammation drives telomere reduction, which may be why shorter telomeres are found in the tissue microenvironment in VV.52,53

Treatment of lipedema improves mental and physical health

Women with lipedema had improved quality of life, pain, bruising, edema, appearance, and multiple other measures after lipedema reduction surgery.54,55 Quality of life for women with lipedema was also improved after the use of an intermittent pneumatic compression de- vice, the ketogenic or Mediterranean diets, and manual lymphatic drainage therapy and vibration.56-59 These and additional recommendations and references can be found in the Standard of Care for Lipedema in the US.60

How can we promote good mental health for our patients?

The WHO defines mental health promotion as actions to create living conditions and environments that support mental health and allow people to adopt and maintain healthy lifestyles.61 To promote mental health literacy among the public in China, the saying “mental illness is

like any other illness” has become pervasive, and should be considered worldwide.62 Young people describe barriers to seeking mental health treatment including perceived stigma and embarrassment, problems recognizing symptoms (poor mental health literacy), and a preference for self-reliance.63 However, they perceived positive past experiences, social support, and encouragement from others as aids to the help-seeking process.64

Addressing and improving mental health is import- ant to healthcare as a population-based cohort study of 991,445 adults in Canada found that people with mental health disorders have substantially higher resource utilization and health care costs among patients with chronic diseases.65

We first need to recognize there is a disease. Questionnaires are one way to accomplish this. Clinical practices are different, therefore the choice of which questionnaire to use should be personalized. There are at least 29 adult and 20 youth questionnaires that are free, can be accessed through a website or by emailing the author, and contain less than 50 items each.66 These questionnaires cover anxiety, worry, depression, suicide risk, recovery, trauma, and overall mental health risk. (See also Table 1.)

Once a mental health disease is identified in our patients with vascular disease, the next step can be improving the physical and mental health of your patients with personalized care planning, a conversation, or a series of conversations, in which you and your patient both agree on goals and actions; in essence, empower your patient to manage their health problems. Knowing that mental health issues can be different in men and women can help guide your conversation.67 Personalized care planning is a conversation or series of conversations in which you and your patient both agree on goals and actions; in essence, empower your patient to manage their health problems.68 Conversations are more effective if they happen frequently, which can be difficult in today’s healthcare setting. Conversational agents might help support personalized care planning. Conversational agents are software programs that use artificial intelligence to simulate a conversation with a user through written text or voice, such as Siri (Apple) Cortana (Microsoft), Google Now, and Alexa (Amazon). There is early evidence suggesting that conversational agents are

acceptable, usable, and may be effective in supporting self-management.69 The style of the conversational agent can vary between paternalistic, informative, interpretive, or deliberative.70 There are no conversation agents for CVD, lymphedema or lipedema but it would not be surprising if the development of these programs were underway.

Conclusion

Most people with chronic venous disease, lymphedema, or lipedema are women. These vascular diseases are serious health conditions that can affect mental health and be affected by mental health, linked through inflammation in both directions. Women have different mental health issues than men, but both can benefit from having their disorders identified and supported by the community of mental health professionals and also by increased education on mental health, early diagnosis, and personalized care planning. Find the questionnaires that are best for your practice and help your patients with mental health issues — it’s just a disease. V

References

- Boersma, L.I. Black, and B.W. Ward, Prevalence of Multiple Chronic Conditions Among US Adults, 2018. Prev Chronic Dis, 2020. 17: p. E106.

- Novak Sarotar, B. and M. Lainscak, Psychocardiology in the elderly. Wien Klin Wochenschr, 2016. 128(Suppl 7): p. 474-479.

- Chen, C.M., et al., The longitudinal relationship between mental health disorders and chronic disease for older adults: a population-based Int J Geriatr Psychiatry, 2017. 32(9): p. 1017-1026.

- Association, A.P., Diagnostic and statistical manual for mental disorders. DSM-IIIR 精神障害の分類と診断の手引, 1987: p. 3-24.

- American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. 2013, Washington, DC.

- Eaton, R., et al., An invariant dimensional liability model of gender differences in mental disorder prevalence: evidence from a national sample. J Abnorm Psychol, 2012. 121(1): p. 282-8.

- Conner, O., et al., Mental health treatment seeking among older adults with depression: the impact of stigma and race. Am J Geri- atr Psychiatry, 2010. 18(6): p. 531-43.

- Kronish, M., et al., Persistent depression affects adherence to secondary prevention behaviors after acute coronary syndromes. J Gen Intern Med, 2006. 21(11): p. 1178-83.

- Crescenzi, R., et al., Subcutaneous Adipose Tissue Edema in Lipedema Revealed by Noninvasive 3T MR Lymphangiography. J Magn Reson Imaging, 2022. 3(10): p. 28281.

- Kurz, X., et al., Do varicose veins affect quality of life? Results of an international population-based J Vasc Surg, 2001. 34(4):641-8.

- Fu, R., et al., Psychosocial impact of lymphedema: a systematic review of literature from 2004 to 2011. Psychooncology, 2013. 22(7): p. 1466-84.

- Jones, E., et al., Impact of exudate and odor from chronic venous leg ulceration. Nurs Stand, 2008. 22(45): p. 53-4, 56, 58 passim.

- Fusar-Poli, P., et al., What is good mental health? A scoping review. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 31: p. 33-46.

- Piazza, R., et al., Affective reactivity to daily stressors and long-term risk of reporting a chronic physical health condition. Ann Behav Med, 2013. 45(1): p. 110-20.

- Sin, L., et al., Affective reactivity to daily stressors is associated with elevated inflammation. Health Psychol, 2015. 34(12): p. 1154-65.

- Stringaris, A., et al., The Affective Reactivity Index: a concise irritability scale for clinical and research settings. J Child Psychol Psychiatry, 2012. 53(11): p. 1109-17.

- Chakraborti, S., Women with mental illness. A psychosocial perspective in gender and mental health. Combining theory and practice., M. Anand, Editor. 2020, Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.: Singapore.

- Organization, W.H., Mental health: strengthening our response. 2018.

- Brown, L., et al., Grief Symptoms Promote Inflammation During Acute Stress Among Bereaved Spouses. Psychol Sci, 2022. 33(6):859-873.

- Stroebe, , H. Schut, and K. Boerner, Cautioning Health-Care Professionals. Omega (Westport), 2017. 74(4): p. 455-473.

- Kübler-Ross, E., On death and dying. Bull Am Coll Surg, 1975. 60(6): p. 12, 15-7.

- Carré, A., et al., The Basic Empathy Scale in adults (BES-A): factor structure of a revised form. Psychol Assess, 2013. 25(3): p. 679-91.

- Ligi, D., L. Croce, and F. Mannello, Chronic Venous Disorders: The Dangerous, the Good, and the Diverse. Int J Mol Sci, 2018. 19(9).

- See 10

- Paul, J.C., B. Pieper, and T.N. Templin, Itch: association with chronic venous disease, pain, and quality of life. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs, 2011. 38(1): p. 46-54.

- Kaplan, M., et al., Quality of life in patients with chronic venous disease: San Diego population study. J Vasc Surg, 2003. 37(5): p. 1047-53.

- Smith, J., et al., Evaluating and improving health-related quality of life in patients with varicose veins. J Vasc Surg, 1999. 30(4): p. 710-9.

- Siribumrungwong, B., et al., Quality of life after great saphenous vein ablation in Thai patients with great saphenous vein Asian J Surg, 2017. 40(4): p. 295-300.

- Roberts, A., et al., Increased Hyaluronan Expression at Distinct Time Points in Acute Lymphedema. Lymphatic Research and Biology, 2012. 10(3): p. 122-128.

- Pedrosa, B.C.S., et al., Functionality and quality of life of patients with unilateral lymphedema of a lower limb: a cross-sectional study. J Vasc Bras, 2019. 18: p. e20180066.

- See 11

- Violán, C., et al., Comparison of the information provided by electronic health records data and a population health survey to estimate prevalence of selected health conditions and multimorbidity. BMC Public Health, 2013. 13(251): p. 251.

- van den Akker, M., et al., Multimorbidity in general practice: prevalence, incidence, and determinants of co-occurring chronic and recurrent diseases. J Clin Epidemiol, 1998. 51(5): p. 367-75.

- Mäkivaara, A., et al., The risk of congestive heart failure is increased in persons with varicose veins. Int Angiol, 2009. 28(6):452-7.

- Abbasi, B., et al., The effect of relaxation techniques on edema, anxiety and depression in post-mastectomy lymphedema patients undergoing comprehensive decongestive therapy: A clinical trial. PLoS One, 13(1): p. e0190231.

- Şahinoğlu, E., G. Ergin, and D. Karadibak, The efficacy of change in limb volume on functional mobility, health-related quality of life, social appearance anxiety, and depression in patients with lower extremity Phlebology, 2022. 37(3): p. 200-205.

- Angst, F., et al., Cross-sectional validity and specificity of comprehensive measurement in lymphedema and lipedema of the lower extremity: a comparison of five outcome instruments. Health Qual Life Outcomes., 2020. 18(1): p. 245. doi: 10.1186/ s12955-020-01488-9.

- Felmerer, G., et al., Increased levels of VEGF-C and macrophage infiltration in lipedema patients without changes in lymphatic vascular morphology. Sci Rep, 2020. 10(1): p. 10947.

- AL-Ghadban, S., et al., Dilated Blood and Lymphatic Microvessels, Angiogenesis, Increased Macrophages, and Adipocyte Hypertrophy in Lipedema Thigh Skin and Fat Tissue. Journal of Obesity, 2019.

- Blasco, V., et al., Obesity and Depression: Its Prevalence and Influence as a Prognostic Factor: A Systematic Review. Psychiatry Investig, 2020. 17(8): p. 715-724.

- Ghods, M., et al., Disease progression and comorbidities in lipedema patients: A 10-year retrospective analysis. Dermatol Ther, 33(6): p. e14534.

- Herbst, L., et al., Survey Outcomes of Lipedema Reduction Surgery in the United States. PRS Global Open, 2021. 9:e3553.

- Herbst, L., L. Abu-Zaid, and M.T. Fazel, Question-based Self-re- ported Experience of Patients with Subcutaneous Adipose Tissue (SAT) Disease Prescribed Sympathomimetic Amines. Medical Research Archives, 2019. 7(6): p.1-17.

- Fife, C.E., E.A. Maus, and M.J. Carter, Lipedema: a frequently misdiagnosed and misunderstood fatty deposition Adv, 2010. 23(2): p. 81-92; quiz 93-4.

- Stutz, J., All about lipedema. human med AG, 2015.

- Dudek, J.E., W. Białaszek, and M. Gabriel, Quality of life, its factors, and sociodemographic characteristics of Polish women with lipedema. BMC Women’s Health, 2021. 21: p. 1-9.

- Dudek, E., et al., Depression and appearance-related distress in functioning with lipedema. Psychol Health Med, 2018. 3: p. 1-8.

- Zhao, X., et al., The relationship of interpersonal sensitivity and depression among patients with chronic atrophic gastritis: The mediating role of coping styles. J Clin Nurs, 2018. 27(5-6): p. e984-e991.

- Boyce, J.A., et al., Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Food Allergy in the United States: Summary of the NIAID-Spon- sored Expert Panel Report. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2010. 126(6):1105-18.

- See 35

- Suzuki, A., et al., Relationship between interpersonal sensitivity and leukocyte telomere length. BMC Medical Genetics, 2017. 18(1):112.

- Wolkowitz, O.M., et al., Leukocyte telomere length in major depression: correlations with chronicity, inflammation, and oxidative stress--preliminary PLoS One, 2011. 6(3): p. e17837.

- Palmieri, D., et al., Telomere shortening and increased oxidative stress are restricted to venous tissue in patients with varicose veins: A merely local disease? Vasc Med, 19(2): p. 125-130.

- See 40

- Baumgartner, A., et al., Improvements in patients with lipedema 4, 8 and 12 years after Phlebology, 2020. 26(268355520949775): p. 0268355520949775.

- Atan, and Y. Bahar-Özdemir, The Effects of Complete Decongestive Therapy or Intermittent Pneumatic Compression Therapy or Exercise Only in the Treatment of Severe Lipedema: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Lymphat Res Biol, 2021. 19(1): p. 86-95.

- Sørlie, V., et al., Effect of a ketogenic diet on pain and quality of life in patients with lipedema: The LIPODIET pilot study. 2021.

- Di Renzo, L., et al., Potential Effects of a Modified Mediterranean Diet on Body Composition in Lipoedema. Nutrients, 2021. 13(2).

- Schneider, R., Low-frequency vibrotherapy considerably improves the effectiveness of manual lymphatic drainage (MLD) in patients with lipedema: A two-armed, randomized, controlled pragmatic trial. Physiother Theory Pract., 2020. 36(1): p. 63-70. doi: 10.1080/09593985.2018.1479474. Epub 2018 May 30.

- Herbst, L., et al., Standard of care for lipedema in the United States. Phlebology, 2021. 36(10): p. 779-796.

- See 18

- Li, Y. and Q. He, Is Mental Illness like Any Other Medical Illness? Causal Attributions, Supportive Communication and the Social Withdrawal Inclination of People with Chronic Mental Illnesses in China. Health Commun, 2021. 36(14): p. 1949-1960.

- Gulliver, A., K.M. Griffiths, and H. Christensen, Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: a systematic BMC Psychiatry, 2010. 10: p. 113.

- Coulter, A., et al., Personalised care planning for adults with chronic or long-term health conditions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2015. 2015(3): p. Cd010523.

- Sporinova, B., et al., Association of Mental Health Disorders With Health Care Utilization and Costs Among Adults With Chronic JAMA Netw Open, 2019. 2(8): p. e199910.

- Beidas, R.S., et al., Free, brief, and validated: Standardized instruments for low-resource mental health Cogn Behav Pract, 2015. 22(1): p. 5-19.

- See 6

- See 69

- Griffin, A.C., et al., Conversational Agents for Chronic Disease Self-Management: A Systematic Review. AMIA Annu Symp Proc, 2020: p. 504-513.

- Schachner, T., et al., Deliberative and Paternalistic Interaction Styles for Conversational Agents in Digital Health: Procedure and Validation Through a Web-Based Experiment. J Med Internet Res, 2021. 23(1): p. e22919.