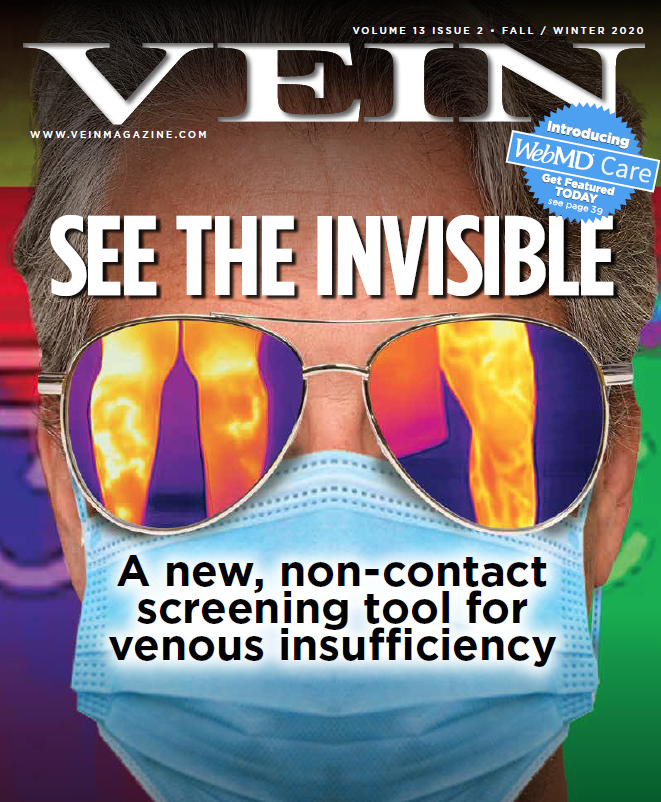

Introducing a new, non-contact screening tool for venous insufficiency

The medical use of thermography is, amazingly, ancient. As far back as 400 BC, physicians commonly applied a thin coat of mud to a patient’s body, observed the patterns made by the different rates of mud drying, and attributed those patterns to temperatures on the surface of the body. As Hippocrates himself described it: “In whatever part of the body excess of heat or cold is felt, the disease is there to be discovered.”

The medical use of thermography is, amazingly, ancient. As far back as 400 BC, physicians commonly applied a thin coat of mud to a patient’s body, observed the patterns made by the different rates of mud drying, and attributed those patterns to temperatures on the surface of the body. As Hippocrates himself described it: “In whatever part of the body excess of heat or cold is felt, the disease is there to be discovered.”

More than two thousand and four hundred years later, thermography is a highly refined science with standardized applications in neurology, vascular medicine, sports medicine, breast health, and many other specialties. Powered by infrared technology, today’s thermography devices offer physicians and patients a way to visualize disease that is indeed waiting to be discovered.

Dr. Ariel Soffer, a triple-board, nuclear-certified cardiologist and peripheral vascular medicine specialist, can attest to thermography’s power to discover the unseen. As one of the founders of ThermPix™—a new clinical application of thermography—Dr. Soffer tells the story of one of the first patients who helped him to see thermography’s potential within venous care five years ago. The patient—an aerobics instructor and mother of three in her thirties—had been suffering from what she believed was restless leg syndrome as well as an intolerance to the medications.

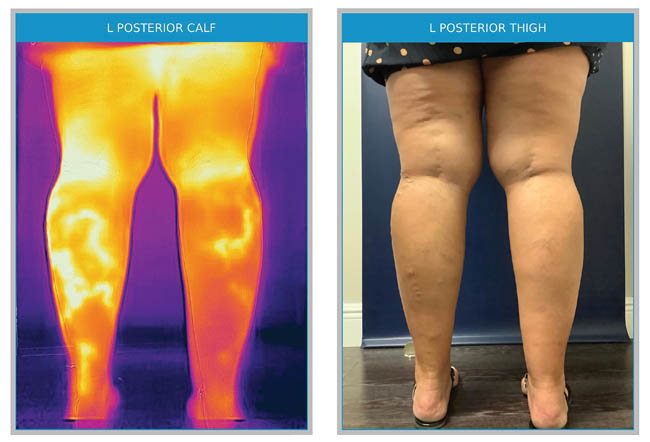

Dr. Soffer saw her in his cardiovascular practice, but as an entrepreneur exploring thermography in venous care, he had the use of a $20,000 bulky thermography camera system by Flir. He took a look at her GSV (great saphenous vein) territory out of curiosity, as the ultrasound lab was backed up that day. “Low and behold, she had very obvious venous insufficiency completely unseeable to the naked eye. In fact, no one had even thought of using compression; she was in such good shape, and her legs seemed flawless. Nevertheless, there it was, ‘screaming’ at us,” he says, “showing an increased temperature radiating in a linear pattern right where we would expect the GSV to reflux. A few hours later, an ultrasound confirmed the diagnosis. She underwent thermal ablation and had immediate and long-standing resolution of symptoms.”

Thermography is proving to be incredibly helpful in spotting chronic venous insufficiency (CVI), according to original research conducted by USA Therm, Inc., the company developing ThemPix.TM The concept is simple: core blood in the body is always measurably hotter than superficial blood. As readers of this magazine know, normal venous flow is typically from superficial to deep veins; venous reflux causes blood to flow in the opposite direction from the deeper trunk and leg vessels to the veins nearer the skin. As Dr. Soffer, his colleagues, and others have found, this abnormal blood flow produces a distinct temperature pattern, and this pattern of higher temperatures, relative to the surrounding tissues, can be used to detect and map venous insufficiency at the surface level.

Dr. Soffer recalls: “The first time I saw veins under ultrasound, I said, ‘Wow, this is really amazing.’ But the first time I saw a thermographic picture of the heat patterns of core blood flowing backward— showing me the nice insufficient vein on the leg—my head really exploded. Just like when I heard my first heart sounds with a stethoscope or saw my first echocardiogram, I felt the same sense of amazement when I saw my first vascular thermogram.”

Since the time Dr. Soffer first became interested in using thermography for venous insufficiency, thermography has undergone a number of important advancements. Five years ago, the device Dr. Soffer had in his office was large and quite expensive. Since then, the devices have become mobile, affordable, and free of radiation. In addition, they are contact-free— they can be used completely remotely if needed. Even more recently, the COVID pandemic has brought thermography to the forefront, as it has become commonly used to read temperatures in malls and restaurants. With the increased visibility, the FDA and

CDC has gotten involved and has started suggesting particular guidelines around thermography—moving adoption of the technology years ahead. All this bodes well for the future of thermography, and Dr. Soffer is very excited about the possibilities.

According to him, there’s a revolutionary advancement in medicine coming—future doctor’s offices with thermography devices as commonly used as the stethoscope and blood pressure cuff. Because of how readily and reliably venous insufficiency shows up on thermography, he sees veins leading the way. As for himself, he’s just looking to be a part of it: “I hope USA Therm is involved in this evolution because that would help me to be part of it. But if it’s not, hey, I’ve added something to the earth, and that’s also gratifying.”

Here we talk to Dr. Soffer about his company, USA Therm, Inc., and the future of medical thermography. Venture into his vision below.

Vein Magazine: Before we talk about thermography, tell us a little bit about you, your professional background, and past ventures.

AS: I am a board-certified cardiologist. I trained at the University of Miami and then Cedar-Sinai for many years. I got extra training in venous pathology and have been doing that for over ten years now.

I became interested in veins early on and was lucky to be a principal investigator in some of the early Varithena trials with David Wright. That led me to really understand the peripheral circulation in its entirety—not only the arterial circulation but the importance of veins—which a lot of us really didn’t focus on until about ten years ago when it started to really take off. I was super lucky to be involved in some of the early teachings that came out around it.

Today, I practice in Miami. Thankfully, I have been able to maintain a nice private practice with a group of clinics that have been relatively successful down here—we were some of the first to do that. We span the gamut from cosmetic work all the way to complicated venous and even arterial pathology in the South Florida area.

VM: You’ve had businesses in this space before; you’ve been an innovator and an entrepreneur. Tell us about that.

AS: When I first got into veins, my mind did enlarge, if you will. I started to think of all the possibilities. Prior to the first intravenous ablations, all we had were some rudimentary surgical techniques and compression socks. When the first radiofrequency and lasers came out, it really started to explode.

I saw this happening in the late 90s, and I was able to find the areas of opportunity and engage with them. I noticed patients really are very happy after an ablation, both cosmetically and from a medical perspective, but often they wouldn’t remember how bad their condition once was. So I started taking a lot of before and after pictures.

In those days, we really didn’t have anything but the big cameras, and it was hard to actually do a quick before and after on a case to show someone, “Hey, you really did make a lot of progress.” When the iPhone came out (I think it was the iPhone 6 that had a camera that was really good), we started using it to take before and afters of vein patients. And then patients went from being kind of happy to, “Oh my God, look at my veins, they look so much better, they feel better but look so much better.” Sometimes looks in those cases were very important because once you feel better, you don’t really remember how you used to feel. But when you look better, you can actually say, “Hey, I look better, and now I feel better.” So my colleagues and I took some software and made it specifically for the iPhone 6, initially. We patented the ability to do before and after photos. We called it “ghosting” and added some other features to make it HIPAA compliant. It was a big deal in those days—because HIPAA had just come out—and then we hosted it on this new thing called the Cloud. All that was really new in the early 2000s when we made a company out of it. Initially, it was called AppwoRx. Since then AppwoRx became an international company, got capitalized, and moved to Boston where it became RxPhoto.

VM: Tell us about your new venture USA Therm. It’s still in an early stage of development. Tell us how it got started and what the mission is.

AS: We have been working on the clinical application of thermography, called ThermPix,™ for nearly five years. The idea for ThermPix™ came from a chance meeting with Dr. David Wright (at that time, the CSO for Varithena at BTG plc) at a Principal Investigator Meeting in California. Because I had previously co-founded a clinical photography software application company, David was interested in how thermography might be applied in a working vein clinic and how these images might add value to patients, physicians, and vascular technicians.

This led to David visiting the Soffer Health offices in South Florida, where we began investigations by comparing thermographic pictures alongside our routine clinical photography and correlating them to ultrasound results. It was immediately apparent that this was an entirely new way of seeing CVI. For the first time, what was clear to the physician utilizing ultrasound evaluation could be communicated to the patient, with a single thermographic image. Because a thermographic picture clearly “lights up” reflux hotspots in the leg, thermography establishes a means to expedite the diagnostic workup with ultrasound for the technician and enables the vascular technologist to pay particular attention to certain areas of insufficiency.

Right anterior accessory vein that connects all the way to the ankle, invisible to the naked eye, very symptomatic, missed by the original ultrasound mapping, but after thermography became very obvious to the technician.

After successful ablation of the truncal greater saphenous vein, this patient was found to have a residual anterior accessory vein that was not obvious to the naked eye, but was highly symptomatic and subsequently treated with complete resolution of symptoms and thermographic temperature gradients.

This patient had been treated prior with successful ablation of the small saphenous vein on the right. Notice the remaining branch on the right and the clear small saphenous territory remaining on the left.

VM: That sounds like a Eureka! moment— what happened next?

AS: We presented our early results with a poster at the American Vein and Lymphatic Society (AVLS) and at the New Cardiovascular Horizons (NCVH) Vein Forum in New Orleans in 2018. Memorably, at that meeting, we also gave a “double act” performance whereby we contrasted David’s veiny, athletic, legs with mine. As expected, David’s legs, which are superficially competent, did not reflect under thermography.

My legs, however, lit up due to my insufficient vasculature. Competent veins are thermographically silent because they are the same temperature as the surrounding tissues. Incompetent veins “light up” due to the relative temperature difference between the skin temperature and their deeper, core blood source. The clarity of such a comparison was very inspiring, as very few things in medicine are as easy to visualize.

Upon our return to Florida, we serendipitously had a small stand at a local health fair. We quickly saw a long queue of symptomatic patients who were eager to see their leg veins light up. They responded with an increased demand for compression stockings after seeing their thermographic image and gaining a better understanding of their potential leg issues.

Despite the reception at the health fair, we recognized the available technological solutions were bulky, expensive, and immobile. At the time we had reviewed the literature about clinical thermography, there had been some skepticism due to recent, flawed data in the mammography space. Because breast tissue is inherently deeper and denser, heat patterns are less likely to be as consistently evident. Thus, thermography is not as well-suited for mammography, but it is perfectly suited for use with CVI.

We sought to do two things: investigate technological solutions that are portable, affordable and FDA approved, and to develop robust clinical evidence of the utility of thermography with CVI. We are making great progress on technology,

and we have patents pending both nationally and internationally. We look forward to some near-term announcements on our R&D progress.

VM: Besides you and David Wright, who else has involved in USA Therm?

AS: We were lucky early on to get lots of interest from a variety of corporate partners. Ultimately, we chose to work with Juzo, the international compression garment company. Juzo immediately saw the benefit of being able to help diagnose and educate more people with appropriate venous insufficiency using such visual technology. Because of its exceptional user ability and opportunity to make a difference in CVI awareness. As Juzo is already a world leader in compression socks, they seemed like the perfect partner for us to develop this technology properly.

AS: We were lucky early on to get lots of interest from a variety of corporate partners. Ultimately, we chose to work with Juzo, the international compression garment company. Juzo immediately saw the benefit of being able to help diagnose and educate more people with appropriate venous insufficiency using such visual technology. Because of its exceptional user ability and opportunity to make a difference in CVI awareness. As Juzo is already a world leader in compression socks, they seemed like the perfect partner for us to develop this technology properly.

Dr. Craig Walker, the founder of NCVH, was also an initial enthusiast and collaborator, and we are grateful for his involvement. We are currently working with a few leading, large vein franchise clinics to optimize the protocols for more and more vein doctors to best utilize for their specific practices.

Dr. Steve Elias, whom many in the vein community know, is heading our scientific advisory board.

VM: Tell us a little more about your insights from clinical development?

AS: With several thousand cases available for comparative analysis, we have conducted a retrospective study that has been submitted for review and will be made available as a reprint on our website, www.usatherm.com.

Comparing the efficacy of thermography to duplex ultrasound for detecting superficial venous insufficiency in a consecutive group of 100 patients, we were stunned by the correlation. Our sensitivity was 95 percent, and our specificity was 100 percent! This meant we had no “false negatives.” We were not surprised; other than incompetent veins, nothing can really leave such a heat signal on the leg. Thermography is incredibly consistent and efficient at picking up this subtle, relative temperature difference.

We then compared two sets of 101 patients from 2017 (prior to our use of thermography), versus 2019 (when thermography was used in each case). Not surprisingly, after the introduction of thermography, we found 24 percent more clinically relevant and incompetent veins overall (as documented by ICAVL ultrasound). Despite the increase, we found the throughput in our labs increased due to the technicians being able to more efficiently map the venous anatomy by using thermography prior to the ultrasound. The net result was patients utilizing compression earlier and the optimization of clinically appropriate procedures. These results, in turn, improved the clinical outcome of that patient population.

Dr. Soffer demonstrates thermal imaging to most of his patients. He found this leads to better understanding, satisfaction, and ultimately compliance with compression and other treatment recommendations.

VM: Let’s switch gears and talk a little about timing. Generally speaking, how has COVID- 19 affected clinical thermography?

AS: I don’t want to sound too grandiose, but COVID-19 was the 9/11 moment for thermography. In the same way 9/11 advanced security measures like airport screening post-9/11, COVID-19 has brought temperature screening and the use of technologies, like thermography, to the forefront to measure relative temperature difference in a contactless way. Thermal imaging had been advancing nicely over the last ten years, but after the pandemic, changes have been made in record time. How many times have you seen pictures of people getting their temperature with thermographic cameras from afar in malls, restaurants, hospitals, etc.? It wasn’t really happening before COVID, but now it’s commonplace. We feel thermography will become commonly used in medicine going forward.

Unfortunately, it took a watershed moment like a global catastrophe to make us all realize just how much information was available by understanding skin temperature patterns. It seems incredible how we might have ignored the information the human body is trying to tell us in situations like infectious disease, certain cancers, rheumatologic disease, and, of course, circulation irregularities. When I walk into a patient room and get to see the thermographic patterns a patient has, I feel like I finally put on my glasses and can see ever so much more clearly and efficiently!

VM: What insights have you developed from the use of Thermography during COVID?

AS: It has been gratifying to see that the world recognizes the potential for thermography to make a difference in health care. Clearly, thermography is useful from a typical social distance (1–2 meters), as non-contact image acquisition, and can detect subtle temperature differentials within one degree Celsius. The benefits of thermography in what we call the “new normal COVID-19” environment are just now being understood. We have been working with scientists from all over the world (Israel, South Africa, the UK, Eastern Europe, etc.). These international collaborations have allowed USA Therm to add benefit to the world experience of thermographic pattern recognition, particularly as it relates to the vascular clinic. We have been closely working with others that are developing “fever- detection methods” to aid in the current pandemic.

VM: What does that look like in practice?

AS: Particularly, in this “new normal COVID-19” setting, we have developed some innovative techniques. Our technicians now utilize ThermPix™ prior to each ultrasound, as it has become an indispensable tool in performing more comprehensive mapping studies.

It allows our technicians to work more efficiently, which means less contact time with the patient, and it gets patients in and out faster. This ensures less risk and exposure for all. In some practices, we have set up ThermPix™ in the front offices to capture the interest of our patients as they walk by, and it often leads to additional dialogue. At other sites, medical assistants capture photographs and thermographic images simultaneously with the snap of one button by utilizing dual-lens technology.

Clinicians that have used it often say that they now feel “blind” without it and that their patients easily relate to and understand the thermographic images much better than with ultrasound images alone or a written report.

VM: Besides COVID, what are some of the other significant thermography developments?

AS: As the worldwide use of the technology has increased, particularly during the pandemic, we have begun to identify certain patterns of skin temperature in normal and abnormal human functions. For example, a colleague of ours in South Africa has identified a unique thermographic pattern seen with COVID-19 ICU patients that may soon prove clinically useful.

In the past, clinical abnormalities have often been diagnosed by visual, subjective, and objective analysis of the anatomy and, more recently, by clinicians looking at the thermograms. However, no matter what the diagnostic methodology, human-based diagnoses are likely to be influenced by many subjective factors. Recent advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning have opened a new path for effective computer-aided medical diagnosis, particularly using technology as elegant and reproducible as thermography. While we have been focused on the venous circulation for thermographic pattern recognition, our collaborators and colleagues have begun looking at arterial disease, rheumatological disorders, and even cancers of the skin.

Ultimately, we believe that clinical thermography aided by pattern recognition and AI will continue to grow as an indispensable non-contact, radiation-free, mobile, and inexpensive adjunctive diagnostic tool.

VM: How do you foresee the future of clinical thermography?

AS: In my opinion, given all that is happening now around the world in understanding the power of thermography and all the data that is being collected at USA Therm, I see the transformation of the basic clinical office. We believe our device will lead the way and end up right next to the blood pressure cuff, stethoscope, otoscope, etc. in every examination. Just as we take a visual inspection of every patient we see (with our eyes), then assess the pressure put on the circulatory system (with BP Cuff), we will be able to assess the temperature patterns of the entire body (with thermography). By collecting this data in a meaningful way and correlating it with known pathologies, we can harness machine learning and AI to augment the clinician’s ability to “see” disease in its earliest stages.

Catching a person with a fever walking into a crowded mall is what drives much of the interest today. But many of those folks walk into our office settings with significant venous insufficiency or other circulatory issues that may be similarly easily identified by us. Thus, we might be able to finally close the gap of access and diagnoses for many of the yet undetected patients with venous insufficiency and other circulatory disorders.

VM: You are currently doing research and development on some newer indications and uses for venous thermography. How can people become involved?

AS: We continue to receive interest from new clinicians daily and have added new beta sites to our ever-growing group of users. We hope to fully commercialize our newest software and hardware in 2021, and then we will begin to look at some other very interesting disease processes (dermatological, orthopedic, rheumatological, etc.). If anyone is interested in getting involved with us at an early user or investigator level, we are accepting applications, so feel free to drop us a message at usatherm.com.