by Paul Pittaluga, MD & Sylvain Chastanet, MD

We published some years ago a new approach for the treatment of varicose veins (VVs) called ASVAL (Ambulatory Selective Varices Ablation under Local anesthesia), which showed that single phlebectomies improve the hemodynamics of the venous system and the clinical outcomes even in presence of a saphenous vein (SV) reflux.

Theoretical Foundations

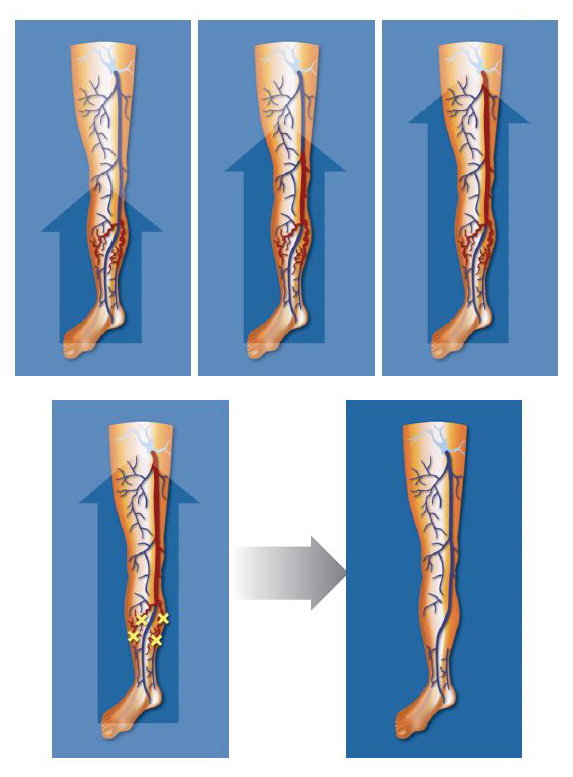

A new physiopathological concept has been brought to light recently; varicose disease could begin at the level of the subfascial tributaries, which are the most superficial and the most exposed, and whose walls are the thinnest.1 The subfascial veins could be the first to dilate through decompensation of their parietal weakness. Progression could initially remain subfascial, creating a dilated and refluxing venous network. When this refluxing network becomes large enough, it could create a “suction” effect in the intrafascial SV, leading to the decompensation of the SV wall, moving forward to reach the saphenofemoral or popliteal junction (fig. 1). In the last decade, numerous publications challenged the theory of descending progression, citing the possibility of local or multifocal early distal evolution, sometimes ascending or anterograde, based on precise and detailed echo Doppler explorations.2,3

Philosophy of Treatment

This physiopathological theory has two consequences:

- Before the emergence of saphenous reflux, early treatment of VVs would be useful in order to prevent it spreading to the SV.

- In presence of saphenous reflux, and up until a certain stage of the disease, first-line therapy should include ablation of the varicose reservoir (VR) and not stripping/ablation of the saphenous vein for which the reflux is potentially reversible (fig. 1).4

Saphenous stripping or ablation would only be indicated in cases where saphenous reflux seems to be irreversible. This approach involves a selective management of the superficial venous refluxes, depending on the clinical and hemodynamic context found in each individual.

Briefly, the best candidates for an ASVAL treatment are the ones with a limited alteration of the SV at the ultrasounds–duplex assessment (limited dilatation of the SV, presence of a segmental truncal reflux, presence of a voluminous/unique varicose tributary ideally at the thigh) and a mild chronic venous disease (CVD) (asymptomatic, cosmetic concern, non complicated C2), especially for young patients and nulliparous women.

The worst patients are those with a severe CVI (C4-C6), with extended damages on the SV (large diameter on a long length, focal dilatations, history of SV thrombosis) or in absence of a large VR.

Fig. 1: Concept of ascending evolution of the varicose disease and effect of the treatment by ASVAL technique.

Diffusion of the Technique

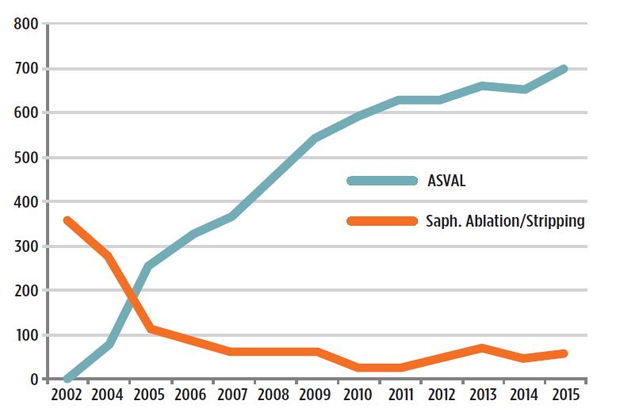

The ASVAL method is nowadays well-known and accepted as an option of treatment for varices in the vascular community. We have 10 years of successful experience in daily practice, with a continuous increase in favor of ASVAL compared to saphenous ablation (fig. 2). We have published 53 original contributions, 34 book chapters, and presented over 400 oral communications about this saphenous sparing approach. Despite all of these elements, there are a limited number of vascular specialists who perform it, especially in the US. Several explanations can be evoked to explain the limited spread of the ASVAL technique, including the absence of strong scientific evidence for criteria to choose the good indications. The American guidelines published in 2011 gave a grade of recommendation/level of evidence 2C mentioning that “although promising results in a group of patients with largely cosmetic concerns, the technique is not generalizable and has to be evaluated in any comparative studies against well-validated surgical techniques.”5 Thanks to new publications about ASVAL, the European guidelines published in 2015 recommended the performance of ASVAL with a class/level of evidence 2B, saying that “in selected patients, with less evolved varicose veins (C2-C3) single phlebectomies with preservation of the saphenous trunk should be considered.”6 Therefore RCTs against other techniques are mandatory to improve the grade of recommendation and the level of evidence for the ASVAL method in the guidelines.

Fig. 2: Evolution of ASVAL and stripping/ endothermal ablation procedures from 2003 at the Riviera Vein Institute.

There are many obstacles for the realization of such studies:

- Most of the varicose veins procedures are performed in private practice and it is hard to randomize a patient between ablation/ conservation of the SV in private practice.

- There is no financial support from the industry for conducting such studies since ASVAL doesn’t need any device.

- It is very difficult to enroll a vascular surgery academic department for a study on VVs, because they may be more focused rather on the arterial disease or the deep venous insufficiency than on the treatment of superficial venous insufficiency.

In addition, because the ASVAL is not exclusive and leaves a place for other techniques according to the indications, an ASVAL “community” doesn’t exist, as it exists for CHIVA which is the unique technique to use for its partisans. Therefore, there are a very limited number of centers/institutions offering workshops/training sessions to learn the ASVAL technique. The indications and the microsurgical technique should be taught to enable the physicians to master the ASVAL technique properly.

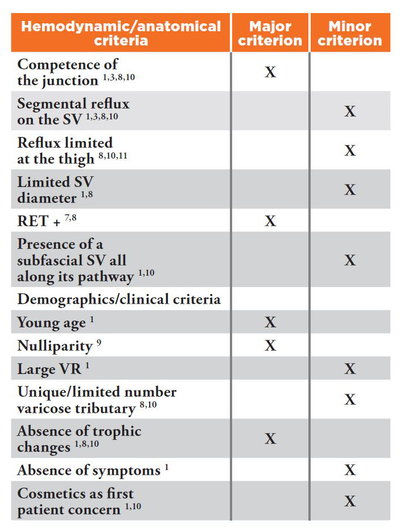

How to Select the Patient in Practice for an ASVAL

According to more than 10 years of experience, and according to the results published in literature,1,3,7-11 we can highlight some simple hemodynamic and clinical criteria in order to determine the patients that can be treated by ASVAL (table 1). These criteria have been divided into hemodynamic or anatomical (US duplex findings) and demographics or clinical (clinical examination findings). We have determined major and minor criteria for each type of criterion depending on their importance for the success of an ASVAL procedure. To simplify, at least one major and one minor (hemodynamic and/ or clinical) criterion should be associated in order to perform an ASVAL. The more criteria there are, the clearer the indication of ASVAL. For instance, the perfect case could be a young nullipara having a 6 mm GSV with a competent JSF and a segmental truncal reflux limited at the thigh, a positive reflux elimination test, a unique and voluminous varicose tributary at mid-thigh extended below the knee and consulting for a cosmetic concern. In this case the patient would have mostly all the major and minor criteria. And it is not uncommon to get such a patient!

Table 1: Major and minor criteria for the selection of patients eligible for an ASVAL procedure.

SV: Saphenous vein.

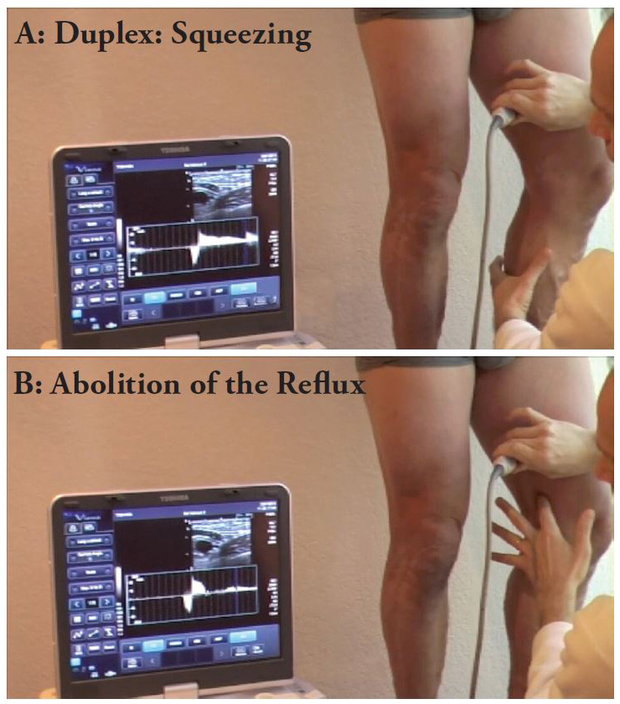

RET +: The Reflux Elimination Test (RET) is considered positive if the reflux of the SV is completely abolished by the compression of the varicose tributary at the moment of the sudden release of manual compression on the calf, during a duplex-ultrasound examination performed with the patient standing upright (fig. 4). We have reported that the positive predictive value of the RET for the abolition of reflux of the GSV was 95.7% and 94.7% at one and two years of follow-up.7

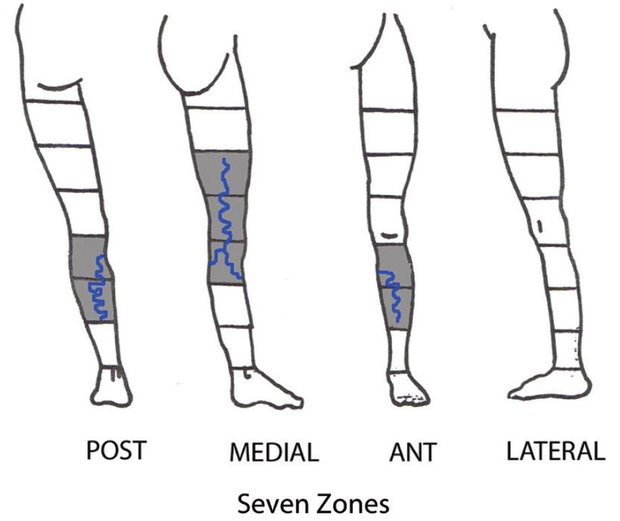

VR: Varicose reservoir. We have reported that the extent of the VR is a determinant factor for the hemodynamic and clinical efficiency of ASVAL.1 The extent of the VR was evaluated according to the number of zones to be treated (NZT) by phlebectomy, with each limb divided into 32 zones in the preoperative clinical mapping (fig. 3). This arrangement reflects our clinical examination technique, in which we examine each lower limb in a standing position, from the front, the back, and each of its profiles (medial and lateral). Each limb is divided into four surface areas (anterior, posterior, lateral and medial), and then each surface area was divided in eight zones: the thigh into three zones (the upper third, middle third and lower third), the calf into three zones (the upper third, middle third and lower third), plus one zone for the knee and one zone for the foot. We draw on the virgin figure the VVs that are visible or palpable during the examination of each side. We calculate this volume of VR according to NZT. In the example in (fig. 3), the NZT is seven, which means that there are seven zones occupied by VVs. We observed a significant linear trend between the outcomes after ASVAL and the NZT: when the NZT was above seven an abolition of the saphenous reflux was 6.81 times more likely obtained (P=0.037) and a symptom relief 2.91 times more likely achieved (P=0.004).1

Fig. 3: Preoperative clinical mapping shows the limb divided in 32 zones. Example shows seven zones to be treated for varices.

Fig. 4: Reflux elimination test. The reflux provoked by the squeezing maneuver on the calf (A) is abolished by the digital compression of the varicose tributary (B).

Communication About ASVAL

MDs should communicate with patients/media/social networks about ASVAL, explaining the advantages of keeping the SV in order to preserve the venous drainage in the limbs with venous insufficiency. A lot of patients have relatives/friends who have been treated surgically and they know that VVs relapse despite the ablation of the SV. “Saving” the SV could be felt as an added value in favor of ASVAL, especially in absence of competitors around who are performing ASVAL.

The other huge advantage to highlight is the cosmetic outcomes of micro-phlebectomy with immediate results including the absence of inflammation/ pigmentation as compared to sclerotherapy.

How to Perform the Technique

- The skin marking before the surgery is mandatory to perform a thorough ablation of the VR.

- The performance of tumescent local anesthesia is essential for doing ASVAL. It is very efficient for the anesthesia and it dramatically reduces the bleeding by the subcutaneous high-pressure thanks to a large infiltration of liquid. It gives the surgeon an excellent comfort level for removing the VVs. It has been reported that the use of isotonic bicarbonate further improves the efficiency of the lidocaine and reduces the amount of lidocaine necessary, enabling large injection volume of tumescence and the ability to treat a large surface on the lower limb (fig. 5).12

Fig. 5: Tumescent local anesthesia with lidocaine 1% + epinephrine usingisotonic bicarbonate 1.4% as exclusive solution for dilution.

- The VVs are removed by micro-phlebectomy. The incisions are done with an 18-gauge needle (fig. 6). The bevel of the needle makes a flap on the skin that facilitates the penetration of the hook through the skin and gives an excellent cosmetic result. The smaller the hook is, the better the cosmetic result will be. In our experience the best tool is a specific micro hook. The phlebectomy should be atraumatic thanks to a precise skin marking that allows for a micro-incision in front of the vein, avoiding scratching the subcutaneous tissues to get the veins. It is recommended to avoid leaving pieces of VVs in order to get the best cosmetic result since it limits the risk of staining

- The use of magnification glasses is mandatory to properly perform the micro-phlebectomy.

- The use of stitches is not necessary thanks to the limited size of the micro-incisions performed with the 18-gauge needle. The use of stretch strips is recommend in order to avoid blisters.

- Walking is immediate at the end of the procedure and the patient can leave the hospital/office one hour afterwards.

- In our experience wearing a stocking is not necessary after the postoperative day following a mini-invasive procedure.13

Conclusion

The ASVAL technique calls into question the usual approach to systematically treat the SV by stripping, or by endothermal or chemical ablation in presence of VVs with a SV reflux. It is opposite to a modern concept of an individualized “à la carte treatment” since every patient has a different clinical and hemodynamic situation of the disease at the time of treatment, which cannot match to a traditional “one size fits all” strategy. Our 10 years of experience with ASVAL taught us that a treatment focused on the VR can improve the clinical and hemodynamic status, preserve the venous drainage and prevent a predictable deterioration at mid-term in a large group of selected patients.

In addition there is a cosmetic approach for the treatment of VVs with a microsurgical technique. Despite the absence of strong recommendations in the guidelines and before new studies precising them, we now have at our disposal simple tools to evaluate the patients, select the good indications and properly perform the ASVAL technique. We must continue to enroll new centers and institutions that will help further this technique.

References

- Pittaluga P, Chastanet S, Réa B, Barbe R. Midterm results of the surgical treatment of varices by phlebectomy with conservation of a refuxing saphenous vein. J Vasc Surg 2009 ;50 : 107-118

- Labropoulos N, Kokkosis AA, Spentzouris G, Gasparis AP, Tassiopoulos AK. The distribution and significance of varicosities in the saphenous trunks. J Vasc Surg. 2010 ;51:96-103.

- Chastanet S, Pittaluga P. Influence of the competence of the sapheno-femoral junction on the mode of treatment of varicose veins by surgery. Phlebology. 2014; 29(IS): 61-65

- Pittaluga P, Chastanet S, Locret T, Barbe R. The effect of isolated phlebectomy on reflux and diameter of the great saphenous vein: a prospective study. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2010;40:122-8

- Gloviczki et al.The care of patients with varicose veins and associated chronic venous diseases: clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery and the American Venous Forum. J Vasc Surg 2011;53(5 Suppl):2S-48S

- Wittens C et al. Editor’s Choice - Management of Chronic Venous Disease: Clinical Practice Guidelines of the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS). Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2015 Jun;49:678-737.

- Pittaluga P, Chastanet S. Predictive value of a preoperative test for the reversibility of the reflux after phlebectomy with preservation of the great saphenous vein. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord 2014; 2: 105 [abstract]

- Biemans A, van den Bos R, Hollestein LM, et al. The effect of single phlebectomies of a large varicose tributary on great saphenous vein reflux. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord 2014;2:179-187.

- Pittaluga P, Chastanet S. Varicose vein recurrence after pregnancy: influence of the preservation of the saphenous vein in nullipara patients. Blucher Medical Proceedings 2014;1:81-82

- Pittaluga P, Chastanet S. Persistent incompetent truncal veins should not be treated immediately. Phlebology 2015;30:98-106

- Zolotukhin, IA, Seliverstov EI, Zakharova EA, Kirienko AI. Short-term results of isolated phlebectomy with preservation of incompetent great saphenous vein (ASVAL procedure) in primary varicose veins disease Phlebology 2016 ; DOI: 10.1177/0268355516674415

- Creton D, Rea B, Pittaluga P, Chastanet S, Allaert FA. Evaluation of the pain in varicose vein surgery under tumescent local anaesthesia using sodium bicarbonate as excipient without any intravenous sedation. Phlebology 2012;27:368-73

- Pittaluga P, Chastanet S. Value of postoperative compression after mini invasive surgical treatment of varicose veins. J Vasc Surg: Venous and Lym Dis 2013;1:385-91