An Update From Two Leading Vein Specialists

Introduction from Dr. Meissner

PELVIC VENOUS DISORDERS, defined as the spectrum of symptoms and signs arising from the veins of the pelvis(the gonadal veins, the internal iliac veins and their tributaries, and the venous plexuses of the pelvis) and their primary drainage pathways (the left renal vein, the iliac veins, and the pelvic escape points)1 are a complex group of disorders that may include renal symptoms of flank pain and hematuria; chronic pelvic pain in females; symptoms related to pelvic origin, non-saphenous varices in the vulva, posteromedial thigh, and scrotum (varicocele); and lower extremity symptoms including pain, swelling, and venous claudication. Although formerly described by a number of historical syndromes (e.g., pelvic congestion, May-Thurner, and Nutcracker syndrome), the recently described Symptoms-Varices- Pathophysiology (SVP) classification,1 an international project led by the American Vein & Lymphatic Society, provides a much more accurate description of clinical symptoms and underlying pathophysiology.

Among the problems with the older nomenclature is a focus on isolated anatomic and pathophysiologic derangements, such as pelvic venous reflux or venous compression, rather than on the patient’s clinical presentation and the complex and interconnected pelvic venous circulation. This is illustrated by a consideration of venous origin chronic pelvic pain in women. Venous origin pain arises from varices involving the ovarian and uterovaginal venous plexuses. However, as these plexuses are extensively interconnected, similar varices may arise from primary reflux in the ovarian and internal iliac veins, secondary left ovarian reflux associated with left renal vein compression, or secondary left internal iliac venous reflux due to common iliac venous obstruction. The complex nature of pelvic venous disorders, as well as misunderstandings engendered by the continued use of misleading nomenclature, has led to a number of controversies surrounding these disorders.

Understanding the controversies around pelvic venous disorders through research, education and continued conversation is an important focus for the American Vein & Lymphatic Society in 2021 and the years to come. In addition to further research, discussions between AVLS members around these controversies are important for the continued growth and education of our society and the venous and lymphatic specialty.

Introduction from Dr. Pappas

Our understanding of Pelvic Venous Disorders (PeVD) has changed dramatically over the past ten years. Dr. Meissner has nicely outlined the venous anatomy of the abdomen and pelvis and emphasized the inter-connectivity of the pelvic venous plexus. He has stated his strong belief that a thorough venographic assessment of the renal and pelvic venous reservoirs, including the internal iliac veins, must be performed in order to determine appropriate treatment strategies. It is difficult to argue that a thorough anatomic assessment is not necessary to assist the interventionalist with clinical decision-making. In point of fact, there are no clinical trials utilizing current endovascular technologies and little data on the effectiveness of our current treatment algorithms. I would therefore like to spend some time on the controversies regarding the treatment of Pelvic Venous Insufficiency (PVI).

Discussion 1: Pelvic Venous Insufficiency and Pelvic Venous Disorders

Dr. Meissner: Pelvic Venous Disorders are underappreciated as a cause of pelvic pain.

Although chronic pelvic pain, defined as “pain symptoms perceived to originate from pelvic organs/structures typically lasting more than 6 months”2, has a multitude of causes as reviewed by Dr. Pappas, at least some data suggests that pelvic varices are second only to endometriosis as a cause of chronic pelvic pain.3 Despite this, venous disorders are often underappreciated or even discounted as a source of chronic pelvic pain in women. At least some of the blame for this misconception rests with our continued use of misleading nomenclature and failure to educate ourselves about chronic pelvic pain. Pelvic varices may be present in 10- 18% of asymptomatic women, with some evidence suggesting that the development of symptoms is related to levels of inflammatory peptide neurotransmitters.4 However, even among symptomatic women, other potential pain generators are frequently present, perhaps accounting for the observation that 10 – 30% of women fail to improve after a pelvic venous intervention. Successful intervention often requires treatment of these sources of pain as well as the concurrent venous sources. There is also an underappreciation of pelvic pain as a chronic condition that may be associated with dysfunctional pain processing (central sensitization) that requires a multidisciplinary approach to treatment.5 While we clearly need to educate others regarding venous origin pelvic pain, meaningful conversation requires that vein specialists also become familiar with the mechanisms of chronic pelvic pain and its multidisciplinary management.

Dr. Pappas: Is PVI a cause of PeVD?

If you are a venous specialist, this question appears absurd. In reality, the majority of non-venous specialists either don’t know of the clinical syndrome or flat out don’t believe it exists.

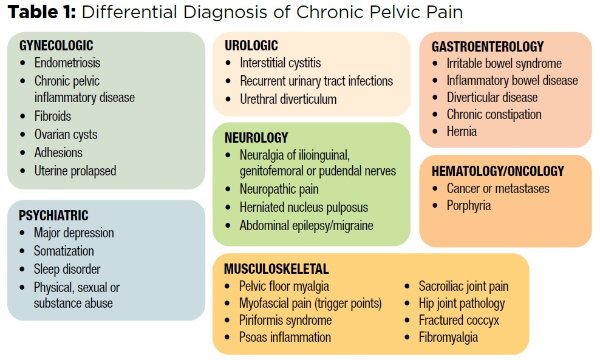

Table 1 provides a short differential diagnosis for chronic pelvic pain.15, 16 Pelvic venous insufficiency is noticeably absent from this list. A recent bulletin published by the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) clearly states that insufficient evidence exists for the existence of Pelvic Congestion Syndrome and that referring patients for treatments is NOT recommended. ACOG’s official position is essentially that the disorder doesn’t exist. Part of the problem is that ACOG is solely focusing on chronic pelvic pain, which is only one aspect of the syndrome. As Mark pointed out, the definition of Chronic Pelvic Pain is non-cyclical pain that exists for greater than six months. This definition is too narrow and ignores symptoms like dyspareunia, flank pain, painful vulvar varicosities, bloating, pelvic fullness, urinary frequency and mid-epigastric pain; all symptoms that don’t fit into the traditional definition for Chronic Pelvic Pain. The term PeVD is a broader term that more broadly encompasses the signs and symptoms consistent with the spectrum of this disorder.

Why is there a lack of consensus on the existence of PeVDs? The three primary barriers to consensus are the following: 1) Lack of a standardized classification system, 2) lack of a survey instrument that measures severity and quality of life impairment, and 3) no randomized clinical trials comparing treatment strategies. As Mark pointed out, the first issue has been addressed by the development of the SVP classification system that was created through a multi-disciplinary effort of various stakeholders.17

The same group is working on a survey instrument to measure severity and quality of life impairment. With the development of a classification system and survey instrument, meaningful clinical trials can be implemented. Our group at the Center for Vascular Medicine is working on a clinical trial and plans to utilize these instruments.

Discussion 2: Clinical presentation and demographics

Dr. Meissner: Demographics are important.

Treatment of pelvic venous disorders is too often treated based on imaging findings without regard for clinical presentation and demographics, both of which are valuable in distinguishing among potential causes of venous origin chronic pelvic pain. Accumulating evidence suggests that patients presenting with pelvic pain as a primary complaint differ from those with both lower extremity and pelvic complaints. Chronic pelvic pain secondary to primary ovarian and/or internal iliac venous reflux tends to primarily affect multiparous women of child- bearing age, many of whom have no leg complaints. The mean age of patients in most series with primary pelvic venous reflux has ranged from 34 – 37 years.

Primary pelvic reflux is unusual in nulliparous women, and among symptomatic women, symptoms tend to improve with menopause. In contrast, patients with primary iliac obstruction tend to be older (average age 39 – 46.4 years) with a high prevalence of concurrent leg signs or symptoms (56% - 79%). 6, 7 In general, patients presenting with pelvic origin leg symptoms, regardless of the pelvic venous etiology, seem to be somewhat older than those presenting with primary pelvic pain. 8, 9 Given

the older patient population and high prevalence of leg symptoms in series demonstrating a benefit from iliac stenting, it is difficult to extrapolate these findings to younger patients having primary pelvic complaints.

Dr. Pappas: Pelvic symptoms vary with age.

Mark and I agree on this topic. As Mark stated, “The mean age of patients in most series with primary pelvic venous reflux has ranged from 34 – 37 years. Primary pelvic reflux is unusual in nulliparous women, and among symptomatic, parous women, symptoms tend to improve with menopause. In contrast, patients with primary iliac obstruction tend to be older (average age 39 – 46.4 years) with a high prevalence of concurrent leg signs or symptoms (56% - 79%) 15, 24

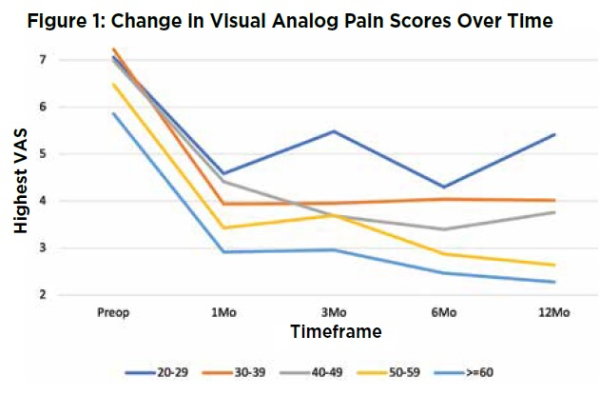

In addition, lower extremity reflux is observed concurrently with PVI in over 50% of women.25 Our group recently analyzed the results of 1,280 women who were treated for PVI and stratified them according to decile age range. 19 We noted that women in their 20s demonstrated an initial response to treatment that was not sustained (Figure 1) beyond three months. This observation strongly suggests that the pathophysiology of pelvic pain in young women is different compared to older women. It also suggests that pregnancy may physiologically protect women from developing severe pelvic pain. The cognitive perception of pelvic pain is extremely complex and discussed in Mark’s exposition.

Discussion 3: Embolization or Stenting

Dr. Meissner: Appropriate treatment algorithms for venous origin pelvic pain remain poorly defined.

Given the misconceptions arising from historical nomenclature, the overlapping pathophysiology of pelvic venous disorders and the lack of rigorously controlled trials, it is perhaps not surprising that treatment algorithms are evolving and that the appropriate management of an individual patient often remains poorly defined. However, algorithms based solely on isolated anatomic or physiologic findings lead to suboptimal results. In patients with appropriate demographic and clinical features, as discussed above, hemodynamically significant obstruction of the left renal or common iliac veins should probably be treated first. However, it must be clearly recognized that these lesions are quite common in asymptomatic women and that hemodynamically significance is not equivalent to simply a ≥ 50% anatomic obstruction. In the case of iliac venous obstruction, hemodynamic significance should be supported by filling of the uterine and vaginal venous plexuses on selective internal iliac venography, in which case filling of the ovarian plexus via the broad ligament as well

Dr. Pappas that ovarian vein dilation may be an adaptive response to iliac outflow obstruction, but in such cases, antegrade flow in the ovarian vein is often seen on selective internal iliac injection and should be considered evidence of the hemodynamic significance of such a lesion. In contrast, reflux in the ovarian vein (on selective ovarian injection) which fills the uterovaginal plexus and internal iliac vein in an antegrade fashion, argues against the significance of an iliac obstruction. Similarly, anatomic compression of the left renal veins may be supported by findings of robust renal vein collaterals, including the left ovarian vein; rapid flow through the pelvic venous plexuses with little contrast stagnation; and antegrade flow in the right ovarian vein.

In cases of primary pelvic reflux, reflux and associated varices in all axial venous trunks, not just the left ovarian vein, should be appropriately evaluated and treated. This does not imply that all of the primary draining trunks of the pelvis (bilateral ovarian and internal iliac veins) should be routinely treated but that their communications with the venous plexuses of the pelvis and associated varices should be routinely interrogated. Inferior results have been reported for isolated embolization of the left ovarian vein without evaluating the right ovarian or internal iliac veins.12 Among 520 women treated with a strategy of routine embolization of all refluxing pelvic venous trunks (bilateral ovarian and internal iliac veins), the visual analog pain scale decreased from 7.63 ± 0.9 before the procedure to 0.91 ± 1.5 after the procedure (p = .0016).13 Although the patient populations are likely not strictly comparable, inferior results have been reported for isolated left ovarian vein embolization with a reduction in VAS pain scores from 7.41 ± 1.33 to 3.15 ± 3.10. 7 Others have similarly reported that symptoms do not substantially improve if all refluxing pathways, particularly those involving the internal iliac veins, are not treated.8

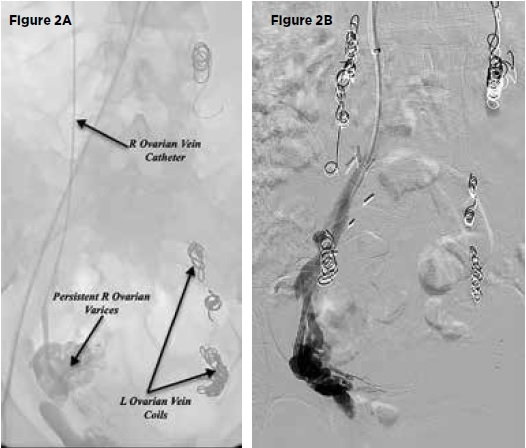

The limited efficacy of isolated left ovarian vein embolization is likely secondary to inadequate penetration of sclerosant through the extensively interconnected venous plexuses of the pelvis. This is supported by the observation that persistent varices can frequently be visualized from selective injection of the right ovarian and internal iliac veins after isolated left ovarian vein embolization. (Figure 2) Among 106 patients undergoing bilateral ovarian embolization, 95 (90%) were found to have residual pelvic varices on follow-up internal iliac venography 4 – 6 weeks later.14

Figure 2: Residual pelvic varices are frequently observed after embolization of one pelvic venous trunk, likely related to both inadequate sclerosant penetration through the pelvic venous plexus as well as altered hemodynamics related to occlusion of an individual trunk.

A. Persistent right ovarian varices after foam and coil embolization of the left ovarian vein and associated left pelvic venous plexus.

B. Persistent right internal iliac varices after foam and coil embolization of both ovarian veins and associated pelvic varicosities.

As discussed above, it can be hypothesized that embolization of an isolated primary draining vein, such as the left ovarian vein, might change pelvic hemodynamics such that persistent varices are now filled by other trunks that were not previously seen to reflux. Dr. Pappas has made the interesting observation that women in their 20’s fail to show a sustained improvement in pelvic symptoms after isolated left ovarian embolization and suggests that this may be due to differing pathophysiology in younger patients. While this could be a consequence of other concurrent generators of pelvic pain in younger women, it is equally plausible that incomplete embolization results in initial improvement followed by deterioration as the hemodynamics change after partial treatment.

While Dr. Pappas is entirely correct that the extent of embolization has not been rigorously evaluated in randomized trials, the treatment group in any future trials should be based on complete elimination of reflux in all trunks communicating with varices of the pelvic venous plexuses. In contrast to Dr. Pappas’ implication, this is not a question of unilateral versus bilateral embolization, but of complete elimination of reflux and associated varices based upon venographic findings in the individual patient rather than proscribed treatment algorithms that do not consider a patient’s clinical presentation or anatomy, which is highly variable. To blindly compare isolated left ovarian embolization with any other treatment modality (medical management, hysterectomy, venous stenting, etc.) will never adequately address questions regarding the value of embolotherapy. Questions regarding the extent of embolization cannot really be answered until the value of complete treatment of all refluxing trunks and associated varices is established. Notably, data is also lacking regarding the relative importance of complete elimination of all pelvic varices with sclerosant versus mechanical occlusion of the associated refluxing trunks, and this will need to be considered in the development of future trials.

Dr. Pappas: What intervention should be utilized to treat PeVD?

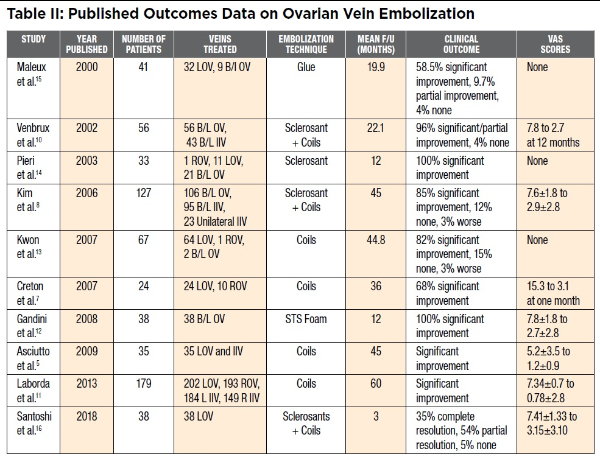

Why is this even a question? Well, up until the last three years, ovarian vein embolization (OVE) has been the standard and primary method utilized to treat PVI. In 2018, our group published our experience treating women with PVI.15 We treated 217 women and divided them into six treatment groups: OVE alone, iliac venous stenting alone, OVE with simultaneous iliac vein stenting, OVE with delayed iliac venous stenting, venoplasty with OVE and venoplasty alone. We reported that 80% of women presenting with symptomatic PVI had an iliac vein obstructive lesion. Only 17% had isolated ovarian vein reflux. This observation is consistent with previously published investigations.18,19 In addition, women who were treated with OVE followed by iliac vein stenting did not report an improvement in their visual analog pain scores in the interval between their OVE and scheduled stenting procedure. Improvement in scores was only observed after the stenting was performed. One criticism of this investigation was that unilateral left OVE alone was performed and that balloon occlusion venography of the internal iliac veins was not assessed, suggesting that residual disease may have been left untreated. Mark points out that two investigations report inferior results when bilateral OVE and balloon occlusion venography are not utilized.20, 21 What he fails to tell you is that the majority of investigations reporting results on OVE employed unilateral OVE without balloon occlusion venography of the internal iliac veins or utilized a combination of unilateral, bilateral and internal iliac vein occlusion regimens. There are no investigations comparing unilateral OVE versus bilateral OVE. Similarly, the role of balloon occlusion venography and its necessity to assess pelvic varices has not been tested in randomized trials either. Table II outlines the results of investigations that assess various endovascular techniques and the outcome tools utilized to analyze success.

Therefore, contrary to Mark’s strong recommendation for comprehensive venographic assessments, it is unclear whether or not bilateral OVE, embolization of a pelvic reservoir and/or balloon occlusion interrogation of the internal iliac veins results in superior and sustainable long-term results compared to more limited approaches.

To try and determine the effectiveness and necessity of OVE, our group analyzed 38 women with combined iliac vein stenoses and ovarian vein reflux.22 All 38 were treated with iliac vein stenting alone, and 78% reported complete resolution of their symptoms. Of the 38 patients, 17 had evidence of a pelvic reservoir. Ten of the 17 patients had asymptomatic ovarian vein reflux after stenting, and six reported partial responses with stenting alone.22 Asymptomatic ovarian vein dilatation and reflux has been previously reported, yet OVE is still proposed as a mainstay of therapy for PVI.23 These observations indicate that ovarian vein dilatation and/or reflux in a significant number of women is not the cause of pelvic symptoms.

Mark would have you believe that when an ovarian vein dilates, flow is always retrograde, leading to pelvic venous hypertension and symptoms. We hypothesize that ovarian vein dilatation is an adaptive response to iliac vein outflow disease. In this circumstance, the ovarian vein acts as an internal escape vein. The vein dilates to accommodate the increased volume and flow of blood now shunted through the ovarian veins. Flow is prograde and would explain why these women are often asymptomatic.

Discussion 4: Non-invasive Imaging

Dr. Meissner: Treatment should not solely be based on non-invasive imaging.

The treatment of pelvic venous disorders is often guided by anatomic findings (ovarian vein dilation, renal vein compression, iliac vein compression) on non-invasive imaging studies. Such studies give little or no information regarding the hemodynamic significance of these findings. While ultrasound may better quantify the degree of reflux or obstruction, it is less good at defining the relative importance of concurrent lesions, which are frequent. As Dr. Pappas notes, determining the relative importance of pelvic venous reflux versus iliac vein compression can be difficult. Additionally, many ultrasound studies focus on the left ovarian and common iliac veins without a thorough evaluation of all reflux pathways, including the right ovarian and internal iliac veins.

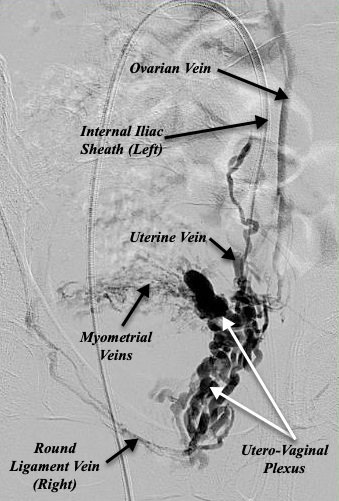

As elsewhere in the venous system, the clinical manifestations of pelvic venous disorders arise from either reflux or obstruction. Symptoms such as pelvic pain arise from varices of the venous plexuses of the pelvis, which drain primarily through the ovarian and internal iliac veins. However, understanding the pathways by which underlying reflux or obstruction communicates within the extensively interconnected pelvic venous circulation is at least as important as identifying the more proximal sources of reflux and obstruction. The internal iliac veins are formed by parietal tributaries, including the obturator, internal pudendal, and superior and inferior gluteal veins, and visceral tributaries, including the uterine, vaginal, and vesicle veins draining the uterine, vaginal, and vesicle plexuses. Not only are varices of these venous plexuses responsible for symptoms, but they also function to connect the ovarian and internal iliac veins on both the ipsilateral and contralateral side of the pelvis. (Figure 3) The utero-vaginal plexus communicates with the internal iliac vein through the uterine and vaginal veins, with the ovarian plexus through the broad ligament, and with the vulva and upper thigh through the pelvic escape points. The ovarian plexus, which normally drains through the ovarian vein, communicates not only with the uterine plexus through the broad ligament but also with the veins of the round ligament. It is likely, although unproven that pressure gradients across the extensively interconnected venous plexuses of the pelvis are changed with isolated intervention on any individual pelvic venous trunk and that, over time, additional trunks may develop reflux and fill any untreated pelvic varices. This may account for the often incomplete response and frequent recurrence of symptoms with simple left ovarian embolization.

Figure 3: Selective left internal iliac venography in a patient with chronic pelvic pain secondary to left common iliac compression. The figure demonstrates the extensive communications of the uterovaginal venous plexus, functionally connecting the tributaries of the internal iliac vein (uterine vein) with the ovarian vein and with contralateral tributaries of the internal iliac and ovarian veins through the myometrial and round ligament veins.

Although optimally guided by ultrasound findings, detailed venography currently provides the best assessment of the extensive interconnections of the pelvic venous circulation. This should include an evaluation of the venous plexuses of the pelvis and their interconnections; an evaluation of reflux in the primary draining veins including both ovarian and both internal iliac veins; and if suggested by ultrasound, an assessment of obstruction in the left renal or common iliac veins. Assessment of the significance of any identified obstruction should be supported by findings of robust collateral drainage pathways. For example, the presence of renal-azygous-lumbar and left gonadal collaterals are suggestive of hemodynamically significant left renal vein obstruction, while ascending lumbar collaterals and reflux into the uterovaginal venous plexus may suggest significant left common iliac venous obstruction. In the case of iliac venous obstruction, this often requires selective internal iliac venography, and balloon occlusion techniques can be helpful in assessing the distal tributaries of the internal iliac veins and pelvic escape points. The role of intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) in defining the underlying etiology of venous origin chronic pelvic pain should be regarded with some skepticism. Although clearly valuable in identifying compressive lesions of the iliac veins and in guiding treatment, its role in predicting the clinical significance of such lesions is limited. For example, among 64 patients undergoing iliac venous stenting for C4 – C6 disease of the lower extremities, the positive predictive value of a ≥ 50% cross-sectional area reduction (IVUS) for clinical improvement, defined as a > 4 point reduction in revised Venous Clinical Severity Score (rVCSS), was < 50%. (Calculated from Gagne PJ et al. 10) As iliac compressive lesions are common among asymptomatic women11, IVUS findings must be supported by features of the patient’s clinical presentation as well as a direct association with varices of the uterovaginal venous plexus on venography. Simply demonstrating reflux into the parietal tributaries of the internal iliac veins, without demonstrable varices in the visceral venous plexuses, should not be regarded as robust evidence of an iliac vein obstruction as a cause of pelvic pain.

If primary reflux is suspected based on ultrasound, venographic evaluation should include both ovarian and internal iliac veins as well as an assessment of flow patterns through the venous plexuses of the pelvis. More than half of patients with pelvic venous reflux have been found to have reflux involving more than one venous trunk.8 Additionally, as discussed above, given the extensively inter-connected venous plexuses of the pelvis, it is possible that veins not initially refluxing on pre-interventional studies may develop reflux as pelvic hemodynamics change after embolization of another venous trunk.

Concluding notes from Dr. Pappas

In conclusion, our understanding of PVI has significantly increased over the past 3-5 years. There is clearly a difference in presentation and response to treatment based upon age of presentation and parity. Women in their 20s should have a thorough evaluation for Gynecologic causes of their pain and don’t respond well to current endovenous therapies. For older women, the current evidence suggests that iliac vein outflow disease is more prevalent than ovarian vein reflux and a significant number of women have asymptomatic ovarian vein dilatation/reflux. In women who require OVE, it is currently unknown whether bilateral OVE with or without internal iliac vein balloon occlusion is necessary or superior to unilateral embolization. Furthermore, to what degree the presence of a pelvic reservoir contributes to pelvic symptoms is currently unknown. With the development of the SVP clinical classification system and a forthcoming clinical severity instrument, meaningful clinical trials will soon be possible.

Concluding notes from Dr. Meissner

The origin of symptomatic pelvic varices is complex, and ovarian/internal iliac vein embolization, stenting of obstructive lesions of the common iliac veins, and treatment of left renal vein compression all have a role in appropriately selected patients with chronic pelvic pain. However, it is concerning that treatment selection is too often based on anatomic criteria such as the degree of venous compression or ovarian vein dilation without a thorough consideration of the patient’s presenting features and detailed venographic evaluation of the associated pelvic varices and their reflux pathways. Determining the significance of either venous reflux or obstruction depends on demonstrating the precise pathways by which such findings are associated with pelvic varices. It is also clear that the extent of embolization is important and that simple, routine embolization of the left ovarian vein is often inadequate. The literature is currently quite difficult to apply to individual patients based on highly variable patient populations (primary pelvic symptoms, predominant lower extremity symptoms or both), imprecise definition of the underlying pathophysiology, and variable extent of pelvic venous embolization.

As evidence accumulates and randomized trials are eventually developed, the importance of defining precise patient populations based on modern classifications such as the SVP instrument cannot be overemphasized.

References:

- Meissner MH, Khilnani NM, Labropoulos N, Gasparis AP, Gibson K, Greiner M, et al. The Symptoms-Varices-Pathophysiology (SVP) Classification of Pelvic Venous Disorders A Report of the American Vein & Lymphatic Society International Working Group on Pelvic Venous Disorders. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2021.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ReVITALize. Gynecology data definitions (version 1.0) Washington, D.C.: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2018 [Available from: https://www.acog.org/-/media/project/ acog/acogorg/files/pdfs/publications/revitalize-gyn.pdf.

- Soysal ME, Soysal S, Vicdan K, Ozer S. A randomized controlled trial of goserelin and medroxyprogesterone acetate in the treat- ment of pelvic congestion. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:931-939.

- Gavrilov SG, Vasilieva GY, Vasiliev IM, Efremova OI. Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide and Substance P As Predictors of Venous Pelvic Pain. Acta Naturae. 2019;11:88-92.

- Hoffman D. Central and peripheral pain generators in women with chronic pelvic pain: patient centered assessment and treatment. Curr Rheumatol Rev. 2015;11:146-166.

- Daugherty SF, Gillespie DL. Venous angioplasty and stenting improve pelvic congestion syndrome caused by venous outflow obstruction. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2015;3:283-289.

- Santoshi RKN, Lakhanpal S, Satwah V, Lakhanpal G, Malone M, Pappas PJ. Iliac vein stenosis is an underdiagnosed cause of pelvic venous insufficiency. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2018;6:202-211.

- Asciutto G, Asciutto KC, Mumme A, Geier B. Pelvic venous incompetence: reflux patterns and treatment results.

Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;38:381-386. - Sulakvelidze L, Tran M, Kennedy R, Lakhanpal S, Pappas PJ. Presentation patterns in women with pelvic venous disorders differ based on age of presentation. Phlebology. 2021;36:135-144.

- Gagne PJ, Gasparis A, Black S, Thorpe P, Passman M, Vedantham S, et al. Analysis of threshold stenosis by multiplanar venogram and intravascular ultrasound examination for predicting clinical improvement after iliofemoral vein stenting in the VIDIO trial.

J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2018;6:48-56 e41. - Kibbe MR, Ujiki M, Goodwin AL, Eskandari M, Yao J, Matsumura J. Iliac vein compression in an asymptomatic patient population.

J Vasc Surg. 2004;39:937-943. - Monedero JL, Ezpeleta SZ, Perrin M. Pelvic congestion syndrome can be treated operatively with good long-term results. Phlebology. 2012;27 Suppl 1:65-73.

- De Gregorio MA, Guirola JA, Alvarez-Arranz E, Sanchez-Ballestin M,

Urbano J, Sierre S. Pelvic Venous Disorders in Women due to Pelvic Varices: Treatment by Embolization: Experience in 520 Patients. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2020;31:1560-1569. - Kim HS, Malhotra AD, Rowe PC, Lee JM, Venbrux AC. Embolotherapy for pelvic congestion syndrome: long-term results. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006;17:289-297.

- Santoshi RKN, Lakhanpal S, Satwah V, Lakhanpal G, Malone M, Pappas PJ. Iliac vein stenosis is an underdiagnosed cause of pelvic venous insufficiency. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2018;6(2):202-11.

- O’Brien MT, Gillespie DL. Diagnosis and treatment of the pelvic congestion syndrome. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2015;3(1):96-106.

- Meissner MH, Khilnani NM, Labropoulos N, Gasparis AP, Gibson K, Greiner M, et al. The Symptoms-Varices-Pathophysiology (SVP) Classification of Pelvic Venous Disorders A Report of the American Vein & Lymphatic Society International Working Group on Pelvic Venous Disorders. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2021.

- Larkin TA, Hovav O, Dwight K, Villalba L. Common iliac vein obstruction in a symptomatic population is associated with previous deep venous thrombosis, and with chronic pelvic pain in females. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2020;8(6):961-9.

- Sulakvelidze L, Tran M, Kennedy R, Lakhanpal S, Pappas PJ. Presentation patterns in women with pelvic venous disorders differ based on

age of presentation. Phlebology. 2020:268355520954688. - Monedero JL, Ezpeleta SZ, Perrin M. Pelvic congestion syndrome can be treated operatively with good long-term results. Phlebology. 2012;27 Suppl 1:65-73.

- De Gregorio MA, Guirola JA, Alvarez-Arranz E, Sanchez-Ballestin M, Urbano J, Sierre S. Pelvic Venous Disorders in Women due to Pelvic Varices: Treatment by Embolization: Experience in 520 Patients. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2020;31(10):1560-9.

- Lakhanpal GK, R.; Lakhanpal, S.; Sulakvelidze, L.; Pappas, P.J. Pelvic venous insufficiency secondary to iliac vein stenosis and ovarian vein reflux treated with iliac vein stenting alone. J Vasc Surg. 2021:in press.

- Rozenblit AM, Ricci ZJ, Tuvia J, Amis ES, Jr. Incompetent and dilated ovarian veins: a common CT finding in asymptomatic parous women. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176(1):119-22.

- Daugherty SF, Gillespie DL. Venous angioplasty and stenting improve pelvic congestion syndrome caused by venous outflow obstruction. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2015;3(3):283-9.

- Scotti N, Pappas K, Lakhanpal S, Gunnarsson C, Pappas PJ. Incidence and distribution of lower extremity reflux in patients with pelvic venous insufficiency. Phlebology. 2019:268355519840846.