In 1985, I became the fifth Dr. Fronek. The medical background of each member of my husband’s family provided an amusing backdrop for many dinner table conversations. While most families might be concerned with the cholesterol content of a food, our conversations centered around whether certain shellfish had higher or lower amounts of sphingomyelins.

In 1985, I became the fifth Dr. Fronek. The medical background of each member of my husband’s family provided an amusing backdrop for many dinner table conversations. While most families might be concerned with the cholesterol content of a food, our conversations centered around whether certain shellfish had higher or lower amounts of sphingomyelins.

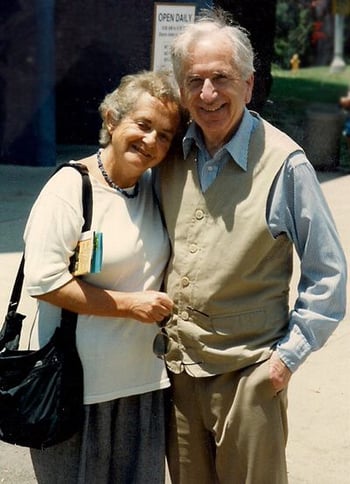

At the time, I didn’t yet realize the significant contributions my new parents-in-law made to what was to become my own field of practice. Drs. Kitty and Arnost Fronek both had illustrious careers expanding the applications of technology in order to add to the understanding of cardiovascular physiology. Few people know of their creativity, tenacity or the importance of their work. As their daughter-in-law, I’ve long admired what they contributed and how they did it—with a consistent attitude of intellectual curiosity, dedication to progress and truth, humility and the highest ethical standards.

Many in the world of phlebology know Arnost Fronek, MD, PhD, as a founding member of the American College of Phlebology. He was born in Slovakia, first displaying his aptitude and unending curiosity for electronics while performing electronic installations and radio repairs as a young teenager. With the spread of Nazism in the 1930s making his future uncertain, his parents sent him to Israel, where he found work in a metal shop before attending the Israel Institute of Technology to study the theory of wireless systems.

Many in the world of phlebology know Arnost Fronek, MD, PhD, as a founding member of the American College of Phlebology. He was born in Slovakia, first displaying his aptitude and unending curiosity for electronics while performing electronic installations and radio repairs as a young teenager. With the spread of Nazism in the 1930s making his future uncertain, his parents sent him to Israel, where he found work in a metal shop before attending the Israel Institute of Technology to study the theory of wireless systems.

As WWII broke out and upon hearing that his parents had been deported to Auschwitz, Arnost joined the Czech brigade of the British Army, where he was tasked with repairing wireless systems in tanks. He still recalls having to leave the relative safety of the tank to perform repairs in the midst of active fighting. When the war ended in 1945, he traveled to Prague to attend medical school at Charles University. His interest in cardiology was heightened during a stint as a general practitioner in a large hospital in Bohemia. This inspired him to join the Cardiovascular Research Institute in Prague, where he became passionate about quantitatively measuring cardiovascular processes.

As WWII broke out and upon hearing that his parents had been deported to Auschwitz, Arnost joined the Czech brigade of the British Army, where he was tasked with repairing wireless systems in tanks. He still recalls having to leave the relative safety of the tank to perform repairs in the midst of active fighting. When the war ended in 1945, he traveled to Prague to attend medical school at Charles University. His interest in cardiology was heightened during a stint as a general practitioner in a large hospital in Bohemia. This inspired him to join the Cardiovascular Research Institute in Prague, where he became passionate about quantitatively measuring cardiovascular processes.

He eventually set his sights on creating a method for determining cardiac output. Using his background in electronics, he initially considered measuring the change in electrical conductivity of a probe after a saline bolus, but settled on thermodilution as a more reliable metric. He imagined that a catheter positioned in the pulmonary artery would offer a way to sample the temperature change that would allow a calculation of cardiac output, but wondered how to reliably position it there. By experimenting with inflated condoms in the bathroom sink, he realized that flowing blood would carry an inflated balloon and eventually allow it to lodge the catheter in a pulmonary vessel. Thus, the pulmonary artery balloon catheter was born.

Later work on this project was done with Dr. William Ganz, a junior member of the institute. Ganz eventually partnered with Dr. Jeremy Swan in Los Angeles to produce the Swan-Ganz catheter after both Fronek and Ganz escaped from Czechoslovakia. While it never bore his name, it was Arnost Fronek who envisioned and created the catheter that was widely used for decades to measure cardiac output, allowing accurate diagnoses and guiding therapy in millions of patients.

Kitty Fronek MD, PhD, began her life in Grenoble, France, and moved to Prague at age 3. After losing both parents by her mid-teens, she was deported to the concentration camp Terezin (Theresienstadt), where her cleverness, tenacity, and superb manual skills allowed her to survive the harrowing years she spent imprisoned there.

Once she was liberated, she returned to Prague with a commitment to resume her education. As a Jew, she had not been permitted to attend school for several years before her deportation, so she had years of curriculum to make up. Three weeks after wondering whether she would survive another day, she was in a classroom trying to focus on the fall of Sparta while suffering from nightmares, digestive problems and difficulty concentrating. It was a testament to her legendary determination and keen intellect that she passed all of her classes in just three months.

Once she was liberated, she returned to Prague with a commitment to resume her education. As a Jew, she had not been permitted to attend school for several years before her deportation, so she had years of curriculum to make up. Three weeks after wondering whether she would survive another day, she was in a classroom trying to focus on the fall of Sparta while suffering from nightmares, digestive problems and difficulty concentrating. It was a testament to her legendary determination and keen intellect that she passed all of her classes in just three months.

She then entered medical school at Charles University, where she met Arnost, her future husband and collaborator. After graduation, she also joined the Cardiovascular Research Institute and began to study hypertension. By externalizing the carotid artery in a skin loop and modifying a blood pressure cuff, Kitty was able to measure the blood pressure of dogs. She studied the effects of conditioned reflexes on blood pressure and then began to measure blood pressure fluctuations when the animals were running, sleeping, eating and after various pharmacologic stressors. It had not been done before.

Although the Froneks were quite happy in their careers at the institute, the communist system did not allow children of educated parents to obtain an education; therefore, their children would have limited opportunities for their future. For this reason, they decided to accept the risk of being apprehended and jailed. In a daring escape, they fled from Czechoslovakia with their children on the pretense of taking a vacation in Bulgaria. Fortunately, they were able to cross the border into Yugoslavia and made their way to Vienna, where the family lived with Kitty’s friend from the concentration camp until they successfully immigrated to the United States, securing jobs in Philadelphia.

Arnost worked at the University of Pennsylvania while Kitty was placed in charge of the experimental surgery lab at Temple University, where she honed her considerable surgical skills and trained surgical residents. The lab provided the necessary facilities and equipment that allowed her to implant blood pressure probes inside major arteries in dogs, and she became adept at performing this procedure so the animals tolerated the probes without change in their activity or comfort.

Arnost worked at the University of Pennsylvania while Kitty was placed in charge of the experimental surgery lab at Temple University, where she honed her considerable surgical skills and trained surgical residents. The lab provided the necessary facilities and equipment that allowed her to implant blood pressure probes inside major arteries in dogs, and she became adept at performing this procedure so the animals tolerated the probes without change in their activity or comfort.

The duo then relocated to San Diego. Arnost joined the newly-formed University of California, San Diego in the Department of Bioengineering, where he turned his attention to peripheral vascular diagnostics. The eminent UCSD vascular surgeon, Dr. Eugene Bernstein, was enthusiastic about collaborating with someone who had Arnost’s understanding of electronics, bioengineering and cardiovascular physiology. He lamented the lack of a laboratory that could be used to measure arterial blood flow.

Meanwhile, also at UCSD, Kitty carried out a series of experiments in which she implanted probes in the aorta, renal, iliac and mesenteric arteries of dogs. This allowed her to study the distribution of cardiac output under different conditions, such as when the dogs were running, sleeping or eating. This groundbreaking work became the basis for later measurements of cardiac output with ultrasound.

As a child, my mother frequently reminded us that we should not exercise for an hour after eating. Little did I know that it was my future mother-in-law who first demonstrated the mesenteric steal phenomenon that my mother based her parental recommendations on!

Kitty’s next area of focus was to experimentally create hypertension. Using Pavlovian theory, she conditioned dogs to expect and thus avoid certain noxious stimuli, and then confused them by providing responses to their behavior that were different than what they had been conditioned to expect. This caused the dogs to become hypertensive.

Kitty’s next area of focus was to experimentally create hypertension. Using Pavlovian theory, she conditioned dogs to expect and thus avoid certain noxious stimuli, and then confused them by providing responses to their behavior that were different than what they had been conditioned to expect. This caused the dogs to become hypertensive.

Discovering this exciting research, a Swiss pharmaceutical company asked her to test their new antihypertensive agent, Rauwolfia. By using this same experimental system, Kitty was able to conclusively demonstrate the antihypertensive efficacy of Rauwolfia.

Following his interest in developing quantitative techniques, Arnost established the first vascular laboratory in San Diego. His comprehensive and richly-referenced 1989 text, Noninvasive Diagnostics in Vascular Disease, provided a thorough description of state-of-the-art techniques used throughout vascular surgery practices and in vascular laboratories throughout the world. Bernstein was also intrigued with Arnost’s experience performing sclerotherapy for varicose veins; Arnost thus began a successful sclerotherapy practice that continued for over a decade. In fact, it was not unusual for me to encounter former patients who fondly recalled his gentle, kind nature and conscientious approach to their care.

Immersed in the field of venous disorders, Arnost collaborated with many European colleagues, most notably Jaroslav Strejcek of Prague and Vladimir Blazek of Aachen, Germany, with whom he worked on expanding the utility of photoplethysmography in the diagnosis of CVI. In recognition of his many contributions over the years, Arnost was honored with Germany’s Humboldt Prize as well as the Conrad Jobst Research Award and the Honorary Member Award from the American College of Phlebology.

Having known these giants of medicine and science for over 30 years, I am humbled by their endless curiosity and dedication to the advancement of whatever aspect of science they found themselves in. Their pursuit of knowledge and drive to answer important questions in science and medicine has been consistently unmarred by scientific competition, ego or financial gain. That they both dedicated their careers to cardiovascular disease is fortunate and a true inspiration for all of us who learned from and followed in their footsteps.

Personally, they are quiet, reserved and disinterested in calling attention to themselves. Given this unassuming presentation to the world and their tremendous service and example, they are quite the vascular dynamic duo.

Personally, they are quiet, reserved and disinterested in calling attention to themselves. Given this unassuming presentation to the world and their tremendous service and example, they are quite the vascular dynamic duo.

After a long and debilitating illness, Kitty Fronek passed away on January 11th, 2018, just before her 93rd birthday. She is greatly missed by many people. Arnost rises every day to the realization that his life partner of 67 years is gone, yet his curiosity and dedication to learning shine through in regular visits to the library and in his avid following of the news. His greatest joy remains spending time with his grandchildren.