As most of us know, Hippocrates wrote more than 30 medical books during his lifetime. One was devoted to the care of patients with various wounds and venous ulcers. In this book, he instructs patients to stop strenuous activities and elevate their legs. For physicians, he instructs them to apply various compression dressings, salves and even how to perform phlebectomies.

As most of us know, Hippocrates wrote more than 30 medical books during his lifetime. One was devoted to the care of patients with various wounds and venous ulcers. In this book, he instructs patients to stop strenuous activities and elevate their legs. For physicians, he instructs them to apply various compression dressings, salves and even how to perform phlebectomies.

Two and a half thousand years later, we had our first major technological advancements. The age of biologic wound dressings and endovenous technologies provided new modalities to treat venous ulcers. Despite this, the global incidence of venous ulceration has not changed.

Venous disease leaders from around the world met in 2005 at the last Pacific Vascular Symposium with the intention of decreasing the incidence of venous ulceration by 50 percent in 10 years. Sadly, this goal has not been accomplished; I believe the primary reason for our failure was in our approach. Many guidelines were published, government agencies were lobbied for research funding, attempts to increase awareness were made, and efforts to form a Joint Venous Council are currently under way.

Although these efforts are noble and useful, they do not address the real need—to rid ourselves of this debilitating disease. We need to focus on the underlying pathophysiology at the tissue level, and get beyond focusing on ways to merely correct the macrocirculatory venous hypertension. In my opinion, those of us who are thought and opinion leaders need to invest more time and energy into seeking the assistance of the pharmaceutical and tissue engineering manufacturing industry to achieve our stated goals.

This is what we currently know about the pathophysiology of venous ulceration:

- Venous reflux and/or obstruction leads to the development of venous hypertension. This hypertension is transmitted to the dermal microcirculation where macromolecules, proteins, fluid and red blood cells (RBCs) are forced out of the circulation and into the dermal interstitium.

- These molecules and RBCs cause an intense and chronic injury stimulus that activates circulating white blood cells. In the beginning, these activated cells clean up the debris that leaks into the interstitium through the production of pro-inflammatory, tissue-destroying chemicals, followed by an orderly process of tissue remodeling.

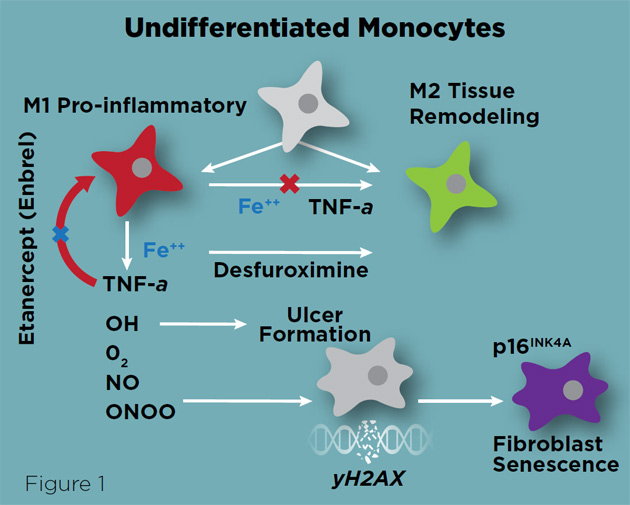

- In venous disease the process goes into hyperdrive, resulting in tissue destruction and fibrosis. We now know that in venous ulcer patients, this pathologic process is caused by an inability of macrophages to switch from a tissue destruction M1 phenotype, to a tissue repair M2 phenotype (Figure 1).

- This inhibition is secondary to iron overload from degrading, extravasated red blood cells. Iron overload stimulates the production of TNF-α from macrophages. TNF-α keeps macrophages in an M1 phenotype and stimulates the production of free radicals and peroxi-nitrates that perpetuate tissue necrosis. It has been demonstrated that dermal injection of Etanercept (a TNF-α inhibitor used to treat Psoriasis, Enbrel or Humira) accelerated wound healing in an iron overload mouse model,.

- In addition, the iron chelator, Desferrooxamine also accelerated wound healing. Finally, we know that living biologic wound dressings like Apligraf placed on surgically-debrided, clean venous ulcers also accelerate wound healing.

Given our current understanding of venous ulceration pathophysiology, I propose that our venous disease leaders lobby Congress, the pharmaceutical and tissue engineering industry to develop products that alter the underlying pathological processes outlined above.

Given our current understanding of venous ulceration pathophysiology, I propose that our venous disease leaders lobby Congress, the pharmaceutical and tissue engineering industry to develop products that alter the underlying pathological processes outlined above.

For example, I propose the following interventions for clinical trial investigation:

- Complete the EVRA trial to determine if surgical or endovenous elimination of venous hypertension accelerates wound healing and increases ulcer-free recurrence intervals

- Approach the makers of Enbrel and Humira and encourage a clinical trial of subdermal peri-wound injection of the TNF-α

- Consider a clinical trial of an iron chelator in acute venous ulcers

- Approach companies like Johnson & Johnson and ask them to develop a biologic wound dressing with an iron chelator or one that produces inhibitors of pro-inflammatory cytokines

- Develop topical pro-inflammatory inhibitors that can be used simultaneously with compression dressings

- Develop non-biologic wound dressings with pro-inflammatory inhibitors that can be placed on the wound and covered with a compression dressing

To achieve these goals, I propose that our national venous societies develop a joint lobbying effort. Specifically I recommend the following:

- Develop a joint societal lobbying group that will advocate on behalf of venous insufficiency patients. Perhaps the Joint Venous Council or American Vein Association.

- Lobby the Blood Division of the National Institutes of Health’s National Heart, Lung and Blood Institutes for venous ulcer funding directed at attacking the pathological processes outlined above.

- Encourage each society’s membership to apply for clinical trial funding to investigate the use of TNF-α inhibitors.

- Target large pharmaceutical and tissue engineering companies to invest research dollars for the development of medications and other biologics to address venous ulceration.

- Provide matching funds from our national venous disease societies to the NIH for funding Venous Disease KO8 training grants.

As stated at the beginning, it is time for a new approach. End-stage advanced venous disease is no longer the black sheep of vascular surgery. In order to decrease the incidence and prevalence of venous ulceration we need to elevate our degree of research, re-engage our government partners and recruit more industry allies. It’s time for a new beginning. We can only accomplish this together as a joint coalition between venous societies and the vein industry.