Recently, the debut of three novel anticoagulants has made a ripple effect throughout the medical community. In this article, Dr. Malay Patel gives us an overview of the individual medications and their impact as a whole, as the world gets ready to integrate these new choices into daily practice.

The new orally active anticoagulants (NOACs), also known as direct anticoagulants (DAs), are challenging oral vitamin K antagonists (OVKAs), which for six decades dominated treatment and management in four clinical settings:

- To minimize or prevent stroke and systemic embolization in adult non-valvular atrial fibrillation (AF);

- To prevent venous thromboembolism (VTE) following hip and knee replacement surgery;

- To treat acute deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE); and

- To prevent recurrent acute DVT and pulmonary embolism (PE).

Early in the last decade, two classes of NOACs/DAs passed clinical trials and became available as prescription drugs to minimize or prevent strokes and systemic embolization in adults with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Further development and extension of their use began in clinical trials to encompass three more indications: to prevent venous thromboembolism (VTE) following hip and knee replacement surgery, to treat acute DVT and PE, and prevent recurrent acute DVT and PE.

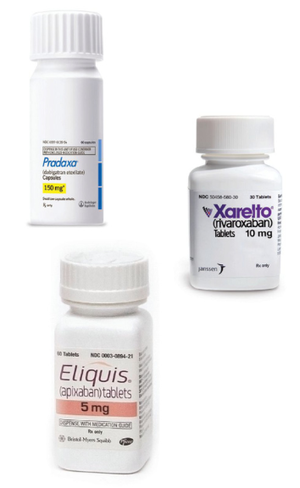

One class of NOACs/DAs consists of the direct thrombin inhibitor, dabigatran (Pradaxa®). The other class consists of the direct factor Xa inhibitors, rivaroxaban (Xarelto®) and apixaban (Eliquis®). Both classes have direct, rapid and predictable onset of anticoagulant activity on oral intake and reliable offset of action. Stable anticoagulation with a wider therapeutic window is achieved due to convenient dosing schedules, fewer probable food and drug interactions, and the appearance that they are not affected by genetic makeup. They do not require laboratory monitoring and are suitable for long-term use.

Rivaroxaban has regulatory clearance in a few countries for the treatment of all four indications. Dabigatran and apixaban, on the other hand, have only been approved for use in the prevention of stroke and systemic embolization in adults with non-valvular AF, and for prevention of VTE following hip and knee replacement surgery. It is simply a matter of time before results from newer clinical trials will convince regulatory authorities to approve current NOACs/ DAs for all four clinical settings.

The question to ask then is, “Will OVKAs lose their stronghold?” Historically, the hold OVKAs have had on the four clinical settings was challenged by low molecular weight heparins (LMWHs), but they stood their ground.

Let us explore this further…

OVKAs have a slow onset of action with a narrow therapeutic window due to interactions with certain drugs and foods containing vitamin K. The individual’s genetic makeup also affects their efficacy. This made periodic monitoring mandatory. While many considered periodic monitoring a disadvantage, some thought it ensured better compliance and kept up contact with the patient. OVKAs are also teratogenic as they may interfere with fetal development and cause birth defects. OKVAs also cannot be recommended for prophylaxis of acute DVT and are unpredictable in cancer patients.

Most of the drawbacks of OVKAs were overcome with the use of LMWHs, specifically in preventing and treating acute DVT. LMWHs have been around for about two decades and they, too, have threatened the virtual monopoly of the OVKAs for this indication. They are faster-acting and more predictable in their onset and offset of action. They also do not require clinical monitoring of blood coagulation parameters, and meta-analysis showed that they were better at treating acute DVT than OVKAs. They are not teratogenic, and most drugs, foods containing vitamin K and genetic factors do not affect their efficacy. Many clinicians started to prefer LMWHs instead of OVKAs, even though they are expensive and must be used subcutaneously. They are probably the only class of drugs that are most reliable in patients on anti-HIV medications. Though they were initially thought to be devoid of serious side effects, reports came in to prove that they could – although rarely – produce heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT). So, despite the fact that LMWHs do not require clinical monitoring for coagulation parameters, the periodic platelet monitoring of patients being treated with long-term LMWHs for treatment or prevention of acute DVT became the norm. This took away one more advantage of the LMWHs.

Most of the drawbacks of OVKAs were overcome with the use of LMWHs, specifically in preventing and treating acute DVT. LMWHs have been around for about two decades and they, too, have threatened the virtual monopoly of the OVKAs for this indication. They are faster-acting and more predictable in their onset and offset of action. They also do not require clinical monitoring of blood coagulation parameters, and meta-analysis showed that they were better at treating acute DVT than OVKAs. They are not teratogenic, and most drugs, foods containing vitamin K and genetic factors do not affect their efficacy. Many clinicians started to prefer LMWHs instead of OVKAs, even though they are expensive and must be used subcutaneously. They are probably the only class of drugs that are most reliable in patients on anti-HIV medications. Though they were initially thought to be devoid of serious side effects, reports came in to prove that they could – although rarely – produce heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT). So, despite the fact that LMWHs do not require clinical monitoring for coagulation parameters, the periodic platelet monitoring of patients being treated with long-term LMWHs for treatment or prevention of acute DVT became the norm. This took away one more advantage of the LMWHs.

Delivering the drug subcutaneously also meant that trained personnel had to administer the LMWH until the patient or their attendant could be trained to do so, unless either one of them were already trained in injecting a drug, such as insulin.

Even though there are therapeutic advantages associated with LMWHs, they never became popular due to the cost, inconvenience of subcutaneous administration and requirement of platelet monitoring. As a result, therapeutic doses of OVKAs continued to hold a dominant position for treatment of acute DVT, VTE and preventing stroke and systemic embolization. Moreover, the use of low dose OVKAs, in some clinical trials, showed that long-term use of either low dose OVKAs and/or anti-platelet drugs could decrease incidence of recurrent acute DVT, sans the monitoring. Thus, the popularity of OVKAs got a boost and their dominance continued.

A few newer developments could also help maintain the dominant position of OVKAs. Knowledge of pharmacogenetics and nutri-pharmacogenetics will improve their dosing. Home testing for OVKA dosing is now a reality and will make it easy for patients to accept a relatively safe, time-tested and inexpensive oral anticoagulation. From December 5, 2011, to June 23, 2014, patient reviews for the home test ‘Coagucheck XS’ on Amazon.com indicated that home-testing is reliable and easily accessible. Out of 18 reviews, 13 were 5-stars, four were 4-stars and only one was 1-star.

Despite this, we are witnessing a second challenge to OVKAs by the NOACs/DAs, and this time around the question is whether the NOACs/DAs will dislodge OVKAs from their dominant position.

Let us take a look at this new challenge and determine how serious it may be.

NOACs/DAs approved for clinical use arrived on the scene during the last two- to four-years, and more recently in developing nations like India. As of today, the orally active factor Xa inhibitor, rivaroxaban, has been approved in a few countries for all four indications. NOACs/DAs have convenient dosing and do not require routine monitoring. But they do have drug interactions, as well as increased anticoagulant activity in the presence of renal and hepatic impairment, and bleeding complications are subtle and insidious.

Studies of other oral drugs have shown that patients tend to miss or forget taking medications, and as high as 20-25% of doses can be missed. If there is a failure in the dosing schedule among patients, then the consequences of a missed dose could be dangerous because they are all short-acting. A missed dose would render a patient coagulable until the next dose takes effect. They are expensive, but over time the costs will decrease.

At present, the NOACs/DAs have no specific antidote. Reversing their action in an emergency, with the available drugs and components, is complex. Very few centers have the infrastructure to access the knowledge and ingredients to reverse their action. Using NOACs/DAs can also raise ethical issues in regions or countries where the action of these drugs cannot be reversed.

We have no information on use during pregnancy, lactation and on long-term use, if required for recurrent acute DVT. Most experts anticipate that in the next few years, research will make reversal of NOACs easier, but until that happens there will always be a conscious concern, if not worry, about using them in regions where there is limited access to sophisticated centers. This will limit their use. There is some encouraging news on the development of an antidote to NOACs/DAs. On May 12, 2014, the following report was released. “Portola Pharmaceuticals (Nasdaq:PTLA) announced that enrollment has begun in a Phase 3 study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of andexanet alfa, the company’s investigational recombinant Factor Xa inhibitor reversal agent, with Bayer HealthCare and Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc.’s Factor Xa inhibitor Xarelto® (rivaroxaban). Portola is developing andexanet alfa, a FDA-designated breakthrough therapy, as a potential first-in-class agent to reverse the anticoagulation activity of Factor Xa inhibitor-treated patients who are experiencing a major bleeding episode or who require emergency surgery.” This drug is given intravenously by a bolus, followed by an infusion to rapidly reverse the anticoagulant effects of rivaroxaban and/or apixaban. The availability of an antidote to NOACs/DAs is eagerly awaited, and a clinically available FDA-approved drug like andexanet alfa could tilt the balance in favor of NOACs/DAs. Hopes for overcoming one major disadvantage for using NOACs/DAs have been raised.

I think it will take another five years before some answers are found to the questions raised by use of NOACs/DAs. I am also aware that some hitherto unknown red flags against NOACs/DAs, as could happen with any new drug, may be raised. One red flag has just been raised in a systematic review and meta-analysis published on June 6, 2014, in the Journal of the American Heart Association stating in the conclusion of its abstract that, “This meta-analysis provides evidence that dabigatran etexilate is associated with a significantly increased risk of myocardial infarction (MI). This increased risk should be considered, taking into account the overall benefit in terms of major bleeding and all-cause mortality.” This red flag is astonishing as it is counter-intuitive. How can an anticoagulant increase ischemic events? It will surely stimulate research trying to find out more about the basic interplay of coagulation factors and vascular physiology. Are we going to see cautions about the use of some or all of the NOACs/DAs, or are we going to see the demise of one or more of them? The study does raise new questions and prods us to think further so that we will find new answers.

Though at present the NOACs/DAs are more patient-friendly, while being as effective as the OVKAs, a definitive word on which oral anticoagulant is preferable has not been written.

The NOACs/DAs are convenient to use, relatively safe and have a predictable action. More clinical trials based on individual preferences and observations will be carried out. This will create niche areas and newer warnings for use of different oral anticoagulants. NOACS/DAs are poised to become the dominant oral anticoagulants of the future. Do not be surprised if you begin to see obituaries for some of the older anticoagulants from the past.

The wise among us will use caution for now.