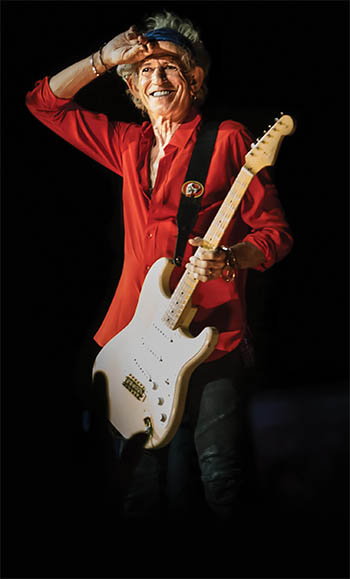

"It’s good to see you. It’s good to see anybody,” says Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones, age 76, in the Martin Scorsese documentary Shine a Light. Richards should be dead many times. He has tried most illicit drugs known to man. He has fallen from a dead tree in Fiji, fell on his head, and needed brain surgery. He has snorted his deceased father’s ashes mixed with cocaine. He has said, “I want to die magnificently, on stage.” Gleefully morbid. Or how about morbidly gleeful, which is how I recently felt?

"It’s good to see you. It’s good to see anybody,” says Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones, age 76, in the Martin Scorsese documentary Shine a Light. Richards should be dead many times. He has tried most illicit drugs known to man. He has fallen from a dead tree in Fiji, fell on his head, and needed brain surgery. He has snorted his deceased father’s ashes mixed with cocaine. He has said, “I want to die magnificently, on stage.” Gleefully morbid. Or how about morbidly gleeful, which is how I recently felt?

I hate to admit it, but I “enjoyed” my 59-year-old cousin’s funeral. Much more than the funeral of my 96-year-old mother-in-law. Not because I didn’t like my mother-in-law. Nice woman as far as an Italian mothers-in-law go, but I couldn’t go to her funeral. Only my wife and one of her six siblings could be there. Those were the “rules” in March 2020. Early COVID, no options. My cousin died in September in Chicago. The funeral home learned a thing or two since March. We all have learned a thing or two since March.

The funeral was live-streamed. The burial was live-streamed. Pre-COVID, you could either be there in person or you missed it all. I would have missed this one. Being there is very hard to do for Jewish funerals outside one’s catchment area under the best circumstances. Jewish law requires Jews to be buried as soon as possible after death, like the next day. It doesn’t give much wiggle room if you need to cancel work commitments, make flight reservations, book a hotel room, and get back home as soon as possible. His funeral, however, was a morbidly gleeful event. My two sisters, my 90-year-old mother, my wife, and I participated and viewed the funeral while sitting in my mother’s apartment in Englewood, NJ. No rushed travel, no disrupted schedule, and no jet lag.

While saddened by the early death of my cousin, we all were gleefully morbid and morbidly gleeful that we could “be there.” Funerals will never be the same; this is here to stay. Can’t you see funeral homes touting their IT Department and their advanced Internet experience? Those who can provide the best camera angles, the most interactive experience. How interactive can it be when someone has died? Probably a one-sided conversation. But everyone can be there without being there. Zooming Funerals is the next big thing. Some people can’t wait to die, knowing they can reach a broader audience. Let’s all say a prayer for the death of the traditional funeral home. Maybe they can live-stream their own funeral: progress and progression.

In this issue of VEIN, we emphasize progress, but no one needs to die. In this issue, most articles are about something new. Daniel Hawkins explains a new concept of utilizing advanced remotely controlled technology to educate physicians and industry as he introduces us to the Avail System. I have a system and have been using it to live-stream cases and educate people. Full disclosure: It is excellent. We’re getting better as time goes on, just like the funeral homes.

We are also getting better with treating acute DVT. The article addressing the unique Thrombolex device tells us how one-stop lysis.

Beyond new is the Star Wars-like technology called HIFU (High Intensity Focused Ultrasound). Michel Nuta explains the technology and early experience. Totally non-invasive. I’ve seen this technology in England. Very cool.

To make better decisions, we need new data. Marlin Schul updates us on the new AVLS Pro Venous Registry, collecting new data in new ways.

Joe Zygmunt has edited a new addition of Venous Ultrasound. Learn what’s new with the old idea of ultrasound.

Our cover article, "See the Invisible," introduces us to another Star Wars technology that enables an entirely contactless screening tool for identifying venous disease. I’ve used this technology. Great potential. It probably will become the initial screening tool before ultrasound, saving a lot of time and money.

Lastly, a discussion that won’t die is the compounding drug conundrum. Nick Morrison leads the conversation that keeps alive the compounding of drugs concept and clarifies what was thought to be a dying concept.

People are dying; people will always be dying. Funerals will never be the same. In 1422 in France, Charles VI died. His son Charles VII became king. When all of this occurred, the people shouted, “Le roi est morte. Vive le roi.” Translated: “The King is dead. Long live the King.” It announces the death of the current king and the ascension of the new king simultaneously.

Keith Richards has died many times, but he is a happy guy. At VEIN, we highlight the living, those who have survived the death of old concepts and constructs, and the birth of new ones. That is what this issue is about. Be morbidly gleeful or gleefully morbid about all of this. The words morbidly and gleeful can be used as dangling participles to describe one’s feelings about death. And the gerund dying allows us to live. To put it all together in a sentence, dangling participle and gerund, one could say: “Dying is a morbidly gleeful and gleefully morbid experience especially for those who are alive.” VEIN is dead, long live VEIN.